A Common Path from Paper to Plaster by Zach Mortice

Summary: The International Masonry Institute’s Masonry Camp has architectural interns and masons learn about the six primary types of masonry and also asks them to design and build a project in an integrated team atmosphere. The camp fosters communication across the two professions and gives architecture graduates the chance to take a more focused view of masonry and materiality while affording masons the opportunity to consider the multidimensional concerns architects deal with while designing.

This common gripe of building craftspeople everywhere was put to rest, at least for a few weeks, this summer during the International Masonry Institute’s (IMI) annual Masonry Camp, which brings architectural interns and apprentice masons together for a week of professional collaboration. Held in two separate week-long sessions this year, August 11-17 and August 18-24, each Masonry Camp brings together 21 architecture graduates and 21 masons, who divide, 3 from each discipline, into 7 teams. At the beginning of the week, masonry instructors demonstrate the six primary masonry forms (brick, stone, plaster, tile, terrazzo, plus restoration) and later campers are asked to design a hypothetical masonry building solution to a proposed problem. This year had campers designing schools for different age groups and student populations. The groups then build one interior and exterior element of their design and are then appraised by the instructors. “The goal of the studio is not to come up with a finished design,” says Maria Viteri, AIA, the IMI Masonry Camp director. “It’s really just to be able to have a mutual experience to create a project that looks more specifically at material.”

Two trades, one industry Or, as camper Benjamin Lindau, Assoc. AIA, says, to bring together two trades that do the same thing but are separated by different industries. “One thing that was refreshing was to see how similar we are in the end,” says Lindau. “We both want to create something.”

Short view, wide view

“I learned how hard it actually is to cut a brick,” says camper Sara Stein, Assoc. AIA. The masonry students, on the other hand, get to pick up all the spatial and functional considerations (foot traffic patterns, safety codes, site relationships, etc.) their architecture-educated teammates cast off. This expanded view of the built environment gives masons a chance to experiment in ways they may not be able to on a jobsite, but it can also be intimidating. “[The masons’] heads are just swimming when they start talking to architects,” says Redabaugh. Burke says the time he spent looking at the big picture has helped his masonry work. “With a mason, we want everything to land on bond,” he says. “We want everything to be modular. From the architect’s end of it, they’ve got to see everything.” |

||

Copyright 2007 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

Photos

1. Bricklayer Jonathan Mezmar from Massachusetts gives bricklaying pointers to Katherine LoBaldo from Robert A.M. Stern, FAIA.

2. Masons get to experience the designers’ jobs in the studio portion of camp. Second from left is Ben Lindau, Assoc. AIA, Ellerbe Becket, Minneapolis.

3. Left to right: Matthew Brind’Amour, Assoc. AIA, Astorino, Pittsburgh; Sarah Walker, Moshe Safdie & Associates, Boston; and BAC apprentice Gene McAndrew.

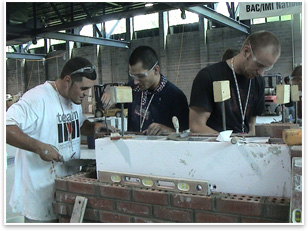

4. Left to right: Bricklayer John Burke; architect Matthew Wilbur, SSOE Detroit; and architect Stephen Shearer from Wight & Co., Ill.

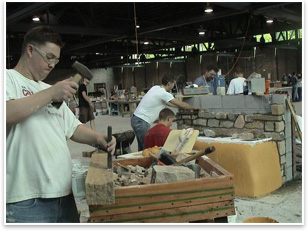

5. Architect Richard Wilmot, Assoc. AIA, from SH Architecture in Las Vegas, in foreground. In background are (left to right) Will Hulver, Assoc. AIA, SOM, Washington D.C. and plaster apprentice Mark Johnston, Jr. from Chicago.

Photos courtesy of the International Masonry Institute.

AIArchitect would like to thank IMI’s Hazel Bradford for her help with this article.

How do you . . .

How do you . . . “Usually when the architect comes around when I’m around, my boss is talking to him, not me,” says apprentice brick mason John Burke of Albany, N.Y., Local 2. “The only time we see them is if there’s a problem.”

“Usually when the architect comes around when I’m around, my boss is talking to him, not me,” says apprentice brick mason John Burke of Albany, N.Y., Local 2. “The only time we see them is if there’s a problem.” After a two-year hiatus, the 2007 Masonry Camp returned to its 15-acre Bowie, Md., home when its new National Training Center was completed. Designed by Stanley Tigerman, FAIA, of Tigerman McCurry Architects, the new facility features a 61,000-square-foot open bay training center with design studios and classrooms and a 46,000-square-foot main building with recreation facilities, a cafeteria, and dormitory rooms for 108 students.

After a two-year hiatus, the 2007 Masonry Camp returned to its 15-acre Bowie, Md., home when its new National Training Center was completed. Designed by Stanley Tigerman, FAIA, of Tigerman McCurry Architects, the new facility features a 61,000-square-foot open bay training center with design studios and classrooms and a 46,000-square-foot main building with recreation facilities, a cafeteria, and dormitory rooms for 108 students. In her career as an architect, Viteri says there used to be more informal interaction between masons and architects, but now quality assurance experts may be the only ones who take any in-depth interest in brick or stonework. But there are bright spots. Viteri says that lately young architects are more intent on assembling multidisciplinary teams for their projects, and that such work gets buildings done more quickly, for less money, and with fewer mistakes. “I think the industry may be pushing us back to a better conversation,” she says.

In her career as an architect, Viteri says there used to be more informal interaction between masons and architects, but now quality assurance experts may be the only ones who take any in-depth interest in brick or stonework. But there are bright spots. Viteri says that lately young architects are more intent on assembling multidisciplinary teams for their projects, and that such work gets buildings done more quickly, for less money, and with fewer mistakes. “I think the industry may be pushing us back to a better conversation,” she says. “With the contacts I have from [the camp], I’m not afraid to call up the people who make it [if I have questions],” says Lindau, an intern at Ellerbe Becket. Lindau used to do construction work and was attracted to Masonry Camp because of the opportunity to get his hands dirty with materials. “If they’re the ones building it, it’s nice to hear what they would recommend. And that’s something that we just don’t have access to in the office.”

“With the contacts I have from [the camp], I’m not afraid to call up the people who make it [if I have questions],” says Lindau, an intern at Ellerbe Becket. Lindau used to do construction work and was attracted to Masonry Camp because of the opportunity to get his hands dirty with materials. “If they’re the ones building it, it’s nice to hear what they would recommend. And that’s something that we just don’t have access to in the office.”