Paralyzed Veterans of America Honors Chicago-based Access Living for Accessible Design by Russell Boniface How do you . . . design an accessible building that incorporates universal and green components?

“I was very proud when we received the award,” says Catlin. Four years ago, Access Living of Metropolitan Chicago, which in addition to its staff serves mainly clients with disabilities, began a fundraising effort for a new building and approached LCM Architects about a state-of-the-art accessible design that would incorporate universal and green components with a modern commercial appearance. Universal but accessible design “The vast majority of their clientele live in poverty because of their disabilities and use public transportation to get to the site,” explains Catlin. “They wanted a site that was easily accessible to public transportation.

They and Access Living held a symposium, moderated by Catlin, with facilities leaders to determine what needed to be addressed. Catlin says the results provided a design roadmap that would combine the special needs of the building’s users but still apply universal elements. “We didn’t want an institutional look,” notes Catlin. “Ninety percent is conventional, but the universal design is applied differently.” Adds Lehner, “Our design goal was that it look like an office building.” Arriving at Access Living

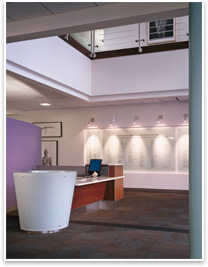

A 12-inch-wide black precast textured strip runs from the middle of the entrance doors across the sidewalk to the curb to allow sight-impaired persons with a cane to detect it. It is black against a light-gray sidewalk for people with some sight to see the contrast. The two sets of main entry sliding doors are hands-free, operating on microwave motion sensors. The strip that starts on the sidewalk is mimicked on the carpet inside to lead people to the reception desk. “The reception desk is on axis with the pair of sliding doors and the vestibule,” notes Catlin. “Using a wheelchair, one can approach it straight on, your knees can go under, and you are at a 30-inch height.” Lehner points out that the reception area underscores the universal design. “A person approaching the reception desk in a wheelchair should have the same ability to use it as a person who doesn’t have a disability. That’s the premise behind the entire design—no one uses a back door or side door, and no one uses a ramp. Everybody comes in the same door and uses the same elevators.”

Adjustable work stations accommodate wheelchair height and power wheelchairs, and low-VOC materials plan for chemical sensitivities. Each floor has two enlarged areas for rescue assistance in an emergency, both equipped with two-way communication. The lighting in the building is on a hands-free motion sensor to adjust amount and intensity. “In the large work areas on a sunny day, the lighting by the windows is barely on, but as you move further away the intensity increases,” explains Catlin. “We also used indirect fluorescent lightning that won’t create seizures.” Water use is reduced through touchless water fountains and faucets. Bathroom soap and dryers are also hands-free, and 10 percent of the building material, including the furniture, use recycled material. Mechanical systems eliminate ozone-depleting refrigerants, and electrical outlets in the garage allow electric cars to recharge. On the top level, a vegetative roof reduces summertime heat and acts as an insulator in the winter. Accessibility for everybody |

||

Copyright 2007 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

home

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› Accessibility Awareness Exercise Gives Architects a New Perspective

› Paralyzed Veterans Honor Chicago’s Millennium Park for Accessibility