05/2005

Edward K. Uhlir, FAIA, Receives 2005 Barrier-Free America Award

by Tracy Ostroff

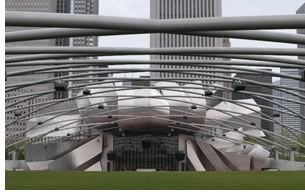

The Paralyzed Veterans of America recognized Chicago’s Millennium

Park and Edward K. Uhlir, FAIA, as the recipient of the 2005 Barrier-Free

America Award. Uhlir received the award May 13 at the park’s Frank

Gehry-designed Jay Pritzker Pavilion.

The Paralyzed Veterans of America recognized Chicago’s Millennium

Park and Edward K. Uhlir, FAIA, as the recipient of the 2005 Barrier-Free

America Award. Uhlir received the award May 13 at the park’s Frank

Gehry-designed Jay Pritzker Pavilion.

Uhlir served as project design director for the collaborative effort behind Millennium Park. PVA, a national veterans’ service and disability rights organization, praised his efforts to make the design accessible. “When the project began, I was challenged to ensure the creation of a world-class park that could be enjoyed by all residents and visitors regardless of their ability.” It’s not just the disabled community who use the ramps, Uhlir notes. The park is filled with strollers, seniors, and young school children for whom he wanted to provide “total inclusion.”

Uhlir says his goal was to redesign it to eliminate stairways wherever

possible and to regrade the park to provide the minimum slopes allowed

without landings and handrails. “We went to a 1-in-20 slope, for

which you can eliminate the landings and handrails which are obstacles

in themselves.” He says the mayor tapped him for the project because

of his long history of providing accessible facilities. During five-year

stint as director of planning for the park districts, the city converted

more than 500 play lots to make them accessible. They then embarked on

a project to make their 500 buildings—many of them historic—accessible. “The

mayor [Richard M. Daley] has a commitment to accessibility,” Uhlir

said. “He intuitively felt that the design could provide much more

inclusion than it did. He asked me to make sure that it was a design

that would move Chicago forward in terms of architecture.”

Uhlir says his goal was to redesign it to eliminate stairways wherever

possible and to regrade the park to provide the minimum slopes allowed

without landings and handrails. “We went to a 1-in-20 slope, for

which you can eliminate the landings and handrails which are obstacles

in themselves.” He says the mayor tapped him for the project because

of his long history of providing accessible facilities. During five-year

stint as director of planning for the park districts, the city converted

more than 500 play lots to make them accessible. They then embarked on

a project to make their 500 buildings—many of them historic—accessible. “The

mayor [Richard M. Daley] has a commitment to accessibility,” Uhlir

said. “He intuitively felt that the design could provide much more

inclusion than it did. He asked me to make sure that it was a design

that would move Chicago forward in terms of architecture.”

Going beyond the law

As the city searched for multiple architects and landscape architects

to get involved in the design for Millennium Park, they mandated for

all the designers chosen “not only to comply with the existing

codes, but to go beyond that and provide total accessibility,” Uhlir

says. Although the city team didn’t put accessibility requirements

in the request for proposals, Uhlir says they had the ability in most

cases to negotiate with the architects, because almost all the architects’ fees

were paid for by private donations.

“We

just made it clear from the beginning that universal accessibility was

one of our goals. There was never any hesitation from any of the architects

not to cut any corners.” Uhlir says one of the ways they

facilitated the integration of accessibility into the designs was to

have all the architects involved with the project sit down with the very

knowledgeable technical staff of the city’s Office for People with

Disabilities early on in schematics to talk about the process and the

goals of the park.

“We

just made it clear from the beginning that universal accessibility was

one of our goals. There was never any hesitation from any of the architects

not to cut any corners.” Uhlir says one of the ways they

facilitated the integration of accessibility into the designs was to

have all the architects involved with the project sit down with the very

knowledgeable technical staff of the city’s Office for People with

Disabilities early on in schematics to talk about the process and the

goals of the park.

Uhlir explains, “We paid attention to things like, if a ramp is required, you don’t want that ramp to go off in some other direction from a stairway. The ramp should begin and end at the bottom and top of the stairway, so that people taking the ramp will still be in the same pathway as people taking the stairs.” Furthermore, they wanted to eliminate stairs altogether. “If the ramp is the means to get from one place to another, everyone would have to take the ramp.” In addition, Uhlir adds, “If there’s a stair, you need an elevator adjacent to it. And ramps make more sense for public safety.”

Accessible, universal design

“PVA and the entire disability community are grateful for the efforts

of individuals like Ed Uhlir who make it a priority not only to address

the everyday challenges facing the disability community, but, more importantly,

provide a blueprint for accessible solutions to these challenges,” states

PVA National President Randy L. Pleva Sr.

“For each section we looked at, we wanted to provide total inclusion.” The

art is interactive, and, in the case of the fountains, they are gathering

places. The fountains—giant towers with faces behind glass bricks—have

reflecting pools with only a quarter inch of water. “I’ve

noticed many people in wheelchairs wheeling through the water with the

people who are able-bodied. There might be people in wheelchairs who

have children who are able bodied and able to play and they are able

to interact with them. We’ve also provided ramps up to the stage

at the Pritzker Pavilion. We wanted to allow people who are in the audience

to come up on stage without having to go by a back route.”

“For each section we looked at, we wanted to provide total inclusion.” The

art is interactive, and, in the case of the fountains, they are gathering

places. The fountains—giant towers with faces behind glass bricks—have

reflecting pools with only a quarter inch of water. “I’ve

noticed many people in wheelchairs wheeling through the water with the

people who are able-bodied. There might be people in wheelchairs who

have children who are able bodied and able to play and they are able

to interact with them. We’ve also provided ramps up to the stage

at the Pritzker Pavilion. We wanted to allow people who are in the audience

to come up on stage without having to go by a back route.”

The lawn is specialized and helps promote accessibility, too, Uhlir says. It has a sand base allowing it to drain very quickly, so that even after a rainstorm it’s usable.

Uhlir’s mission continues as work goes on in Millennium Park. He says it’s important to deal with the community that you are trying to serve early on in the project and to learn from them.

Copyright 2005 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()