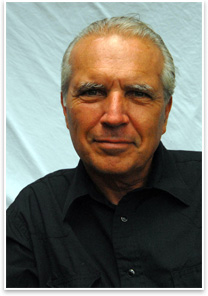

Dan Rockhill Dan Rockhill

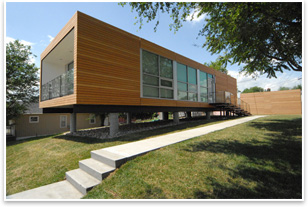

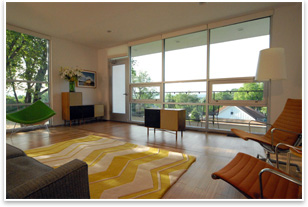

Summary: Dan Rockhill is the founder of Rockhill and Associates and professor of architecture at the University of Kansas. He also is the founder and director of Studio 804, a third-year graduate program that compresses the design-build process into a five-month period. During that time, Studio 804 students bring a housing design to fruition, from design to construction to open house on graduation weekend. His students don’t just learn about the theories of design, they also experience the business realities of practicing architecture. Education: Went to Notre Dame for a bachelor’s degree and SUNY Buffalo for graduate degree in architecture. Career arc: I’ve been teaching for 37 years, so I have always taught and continue to teach here at the University of Kansas. I came here to Kansas in 1980. I have a small practice that, I think by Midwestern standards at least, stands apart from a lot of work here in the Midwest. That’s not to say anything’s better or worse, just different. Most of the work we do tends to be residential in nature, although we’ve done a lot of other work as well. We like to mix things up a bit. I do all of my own construction, and so that frees us up to experiment a little bit more with materials and techniques that ordinarily would be prohibitive if you were trying to do it on contract with somebody else. It’s sort of design-build extreme. So, I wear two hats. One is the Rockhill and Associates and the other is Studio 804, and that is building, which I do with students. Every spring we build a house in the Kansas City area. Founding Studio 804: [It’s been around] 12-13 years now. We didn’t start out doing houses. Back at that time, even the concept of design-build was pretty unique. Architects typically don’t get their hands in the concrete, so I had to go slow and was a little apprehensive about whether it was appropriate for students. I had been teaching studio for my whole life since I graduated from school and the difference between the way we teach studio and the way the real world operates is like night and day. Students are really disappointed in the end when they go out and start to practice. Now, what I do with building [houses] isn’t to turn them into builders. I’m not the least bit interested in that, but I am interested in having them see the tenacity with which you need to go after design and how hard you have to work to make design work. One of the things I’ve found is that being able to get students a little more connected to that aspect of building that ordinarily they shy away from was an important part of their education. I do it because the students want it so much. The students were crazy about it. Over time, we’ve done six houses in Lawrence and four in Kansas City, Kan.

What we’re finding is that young people today don’t want to live in suburbia. They can easily put aside things like curb appeal and resale-ability and that stuff that tends to dissuade most homebuyers, but what we’re finding is that they love Modern architecture. You know, they all read Dwell and they just think it’s fantastic. They can’t get enough of it, so we’re putting the houses in slightly edgy neighborhoods, and we can’t build them fast enough. I mean, I literally have a waiting list for our houses. Where I live, Modern design is seen like the bird flu. They can’t stand it. They hope it goes away, and typically people in the real-estate industry are least receptive to Modern design. So wherever we go we’re always criticized because the work stands out. It completely confounds our critics when these houses sell instantly and nobody is interested in the houses that they’re struggling to sell for half the money. We’re beginning to get a lot of people’s attention for that reason, and they’re beginning to see that Modern maybe isn’t so bad after all.

Typical cost: $140,000 to 200,000. Typical size: The $140K is two bedrooms, 1,200 square feet; and the $200K is three bedrooms, 1,600 square feet, with a full basement. We don’t have any comparables, and that causes problems for us, so we’ve been trying to get our appraisals up as high as possible, which explains going to three bedrooms and 1,600 square feet. The studio process: It used to be for the first nine houses that we started in January, and we would have the houses finished by the third week of May for an open house. That was graduation weekend. In most cases, we didn’t even have a site to start with in January, so you can imagine the speed with which we were moving forward. Now, some of that has changed. Starting just this year, I meet them in the fall for a three-credit-hour experience, and that enables us to get a bit of a jump start on the process. In the fall, this is a three-credit-hour course. In the spring it’s six and three, so it’s a total of 12 credit hours. Guiding principles: In terms of what we do in pushing the envelope, if we don’t [do it] who does? I mean quite frankly the housing industry, despite the vast numbers of houses that are being built, doesn’t experiment. There are very, very few people who do because you have to have a lot of money. It’s very expensive. I honestly think very few people look at alternatives to the way in which we do our housing, so I’m pushing students all the time to push the boundaries on what their expectations of housing should be. For instance, our last house has all moveable walls in it. It is three bedrooms when I talk to the appraiser, but when I talk to some young urban hipster who wants to buy it there are no bedrooms. It’s a loft space, and it’s all done with moveable walls and closets. You’d never find a builder doing it and you’re never going to find people with very limited budgets. That’s one thing that we’ve stumbled into that we really enjoy. Houses, or other structures in the future: I’ve been invited to do a lot of different kinds of projects, and I’m open to the possibilities. There is a distinct advantage to doing a residence from a student’s standpoint because there are problems that need to be solved in every case that I think are important lessons for them to learn—everything from the sewer tap and driveway widths to zoning standards and neighborhood associations. There’s the whole gamut of experience that this brings into play that goes well beyond the hammer and nail. I go out of my way to explain to a lot of people that this is a comprehensive design experience. It’s hard, but the building is almost incidental in the process. There’s so much to deal with. We produce construction documents. We have everything engineered, we have city officials who don’t like us because the work is so different, and on and on and on. That part of the experience is an integral aspect of the program, and I wouldn’t want to lose any part of that. I’m actually starting now a Capstone studio so that I can have people from the profession come, as well as people from other schools. [For] somebody in an office to take a six-month leave of absence to come and have this kind of experience I think would be great. We have had a lot of people who have seen what we do and say that they only wish they’d had that experience when they were in school because the learning curve is just straight up on this. |

||

Copyright 2007 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design