Energy Savings Meets Adaptive Reuse in the NDSU Architecture and Arts School

by Tracy Ostroff

Associate Editor

Summary: Michael

J. Burns Architects Ltd. faced a quartet of issues to orchestrate

an adaptive reuse of a historic warehouse into North Dakota State

University’s Visual Arts and Architecture School, which they

refer to as “NDSU Downtown.” The Fargo project is designed

to the Secretary of the Interior's Guidelines to Historic Rehabilitation

to obtain federal and state tax credits, is LEED® Certified,

meets university programming requirements, and offers lessons in

historic preservation to the art and architecture students within. Summary: Michael

J. Burns Architects Ltd. faced a quartet of issues to orchestrate

an adaptive reuse of a historic warehouse into North Dakota State

University’s Visual Arts and Architecture School, which they

refer to as “NDSU Downtown.” The Fargo project is designed

to the Secretary of the Interior's Guidelines to Historic Rehabilitation

to obtain federal and state tax credits, is LEED® Certified,

meets university programming requirements, and offers lessons in

historic preservation to the art and architecture students within.

The Richardsonian Romanesque warehouse reflects its unique site created by angular streets and railroad boundaries. Several owners changed the appearance of the building, which in 1981 was listed as a pivotal building in the Downtown Fargo Historic District of the National Register of Historic Places. The Richardsonian Romanesque warehouse reflects its unique site created by angular streets and railroad boundaries. Several owners changed the appearance of the building, which in 1981 was listed as a pivotal building in the Downtown Fargo Historic District of the National Register of Historic Places.

At the last minute before demolition, a local investor purchased the building and, after making some minor repairs, donated it to the North Dakota State University Foundation, explains Michael J. Burns, AIA. To handle financing, a syndicated corporation was formed to purchase the tax credits. Burns estimates the city, state, and federal tax credits totaled about $5 million for the $13.1 million project.

Satisfying many constituencies Satisfying many constituencies

The request to satisfy both National Park Service (NPS) and USGBC guidelines “led to an interesting and occasional conflict between what was sought by the park service and what LEED requirements were stipulating,” Burns says. “We had to try to find ways to reach compromise or find other ways to achieve a point for LEED, for instance, if we had to give it up for the tax act requirements.”

The architect had to press the architecture, landscape architecture,

and visual arts studios into 130,000 square feet. “We were

able to take advantage of a partial attic, and so the floor of what

became the fifth floor was actually tucked up in part of the attic

and just above the roof joists,” Burns says. “That helped

us with obtaining the necessary height we needed for the fifth floor

and preserved the sight lines for the visual massing” that

the NPS demands. The architects backed up their decision with sightline

studies and photography.

“On the south side–the lowest point of the roof—there

was no way to avoid that there was an addition. But on that particular

elevation, we had the advantage of having the old freight elevator

tower projecting up.” The architects added a mechanical penthouse

in the rooftop addition, excavated the existing basement, and

put in a small air-handling room for what became part of the altered

first floor.

Because

the building’s original north entrance had been removed, the

architects lowered the northeast corner of the first floor to meet

accessibility standards, provide ample space for the flow of students

through the building, and create the necessary minimum height for

a gallery. They retained the exposed masonry and partially wall-papered

entrance wall, salvaged steel trusses that they removed from several

floors of the eastern half of the building to support the gallery

ceiling, and reused wood joists for ceiling structure and lighting

support. Because

the building’s original north entrance had been removed, the

architects lowered the northeast corner of the first floor to meet

accessibility standards, provide ample space for the flow of students

through the building, and create the necessary minimum height for

a gallery. They retained the exposed masonry and partially wall-papered

entrance wall, salvaged steel trusses that they removed from several

floors of the eastern half of the building to support the gallery

ceiling, and reused wood joists for ceiling structure and lighting

support.

Old meets new

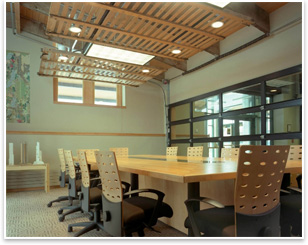

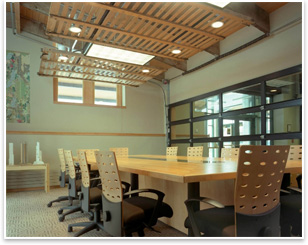

The architects also created an education piece for the architecture

students. “It gives them an opportunity to see how systems

can be integrated within an existing facility and how other techniques

can be employed to increase the connection between the building’s

original history and contemporary use,” Burns says. In the

conference room, for example, they took several freight elevator

slatted doors and made a partial false dropped ceiling. They also

left existing paint on some of the original wood columns, “whether

it matched the design décor or not and left some of the

rubble type walls with several layers of wallpaper on them,” the

architect says. They also created interpretative areas. “Where

we took out floors and had to put in an exit stairway, we cut the

floor joists and left about a foot into the wall and projecting

out into the stairwell to show where the original floor levels

were in relationship to the current stairway,” Burns explains. “It

also showed how the building was partially constructed and supported

originally.”

As the architects worked to meet the NPS requirements, they garnered points for the salvage and reuse of existing materials. They also collected points for efficient energy systems, including flexible air ducts with “duct socks,” extra toilets and showers, bike racks, and a strong connection to mass transit, which students and faculty use to shuttle between the two campuses. As the architects worked to meet the NPS requirements, they garnered points for the salvage and reuse of existing materials. They also collected points for efficient energy systems, including flexible air ducts with “duct socks,” extra toilets and showers, bike racks, and a strong connection to mass transit, which students and faculty use to shuttle between the two campuses.

“From the design standpoint, this was our first attempt at

leaving some of the historic fabric in place and impacting people’s

perception of the building. It provides a visual connection that

is tangible to the building’s history and how the new use can

work around those things,” Burns concludes. |