3/2006

by Russell Boniface

Associate Editor

The redevelopment of the picturesque Grain Belt Brew House in Minneapolis,

with its eclectic blend of architectural styles and unique four tower

roofline, was recently selected to receive a 2005 National Preservation

Honor Award by the National Trust for Historic Preservation. Minneapolis-based

RSP Architects led the Grain Belt Brew House redesign and is also the

primary tenant.

The redevelopment of the picturesque Grain Belt Brew House in Minneapolis,

with its eclectic blend of architectural styles and unique four tower

roofline, was recently selected to receive a 2005 National Preservation

Honor Award by the National Trust for Historic Preservation. Minneapolis-based

RSP Architects led the Grain Belt Brew House redesign and is also the

primary tenant.

Architecture home brew

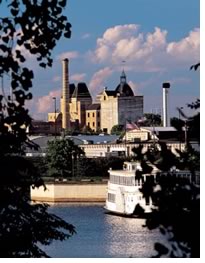

The 100,000-square-foot, six-story castle-like Grain Belt Brew House,

along the Mississippi Riverfront, is a treasured landmark in northeast

Minneapolis within the Minneapolis Brewing Company Historic District,

providing a link to the city’s industrial past. The dramatic

architecture of the 2.95-acre Grain Belt Brew House, built in 1891,

is an architectural mix ranging from Neo-Romanesque, Late Gothic, and

Early Renaissance to Neo-Baroque and Second Empire. The Brew House

is built from materials found in the Twin Cities area, such as cream-colored

limestone and Chaska brick, and features turrets, bulls-eye dormer

windows, exterior painted murals, and monolithic arches with large,

stone voussoirs. The four towers that create the Brew House’s

roofline represent the merger of four brewing companies in the late

19th century that formed the Minneapolis Brewing Company, which operated

in the single structure.

The Grain Belt Brew House, designed by nationally renowned brewery architects

Frederick Wolff and William Lehle, is part of a larger, 14-acre complex

that comprised the Brew House, which included a boiler house, a German-style

tavern, a warehouse of large grain bins, a bottling house, and an office.

The name refers to the "Grain Belt" of the American Midwest

where much of the world's supply of soybeans and grain is produced. Grain

Belt beer was popular in the upper Midwest from its inception well

into the 1960s and came in amber glass bottles and cans, becoming the

flagship brand of the Minneapolis Brewing Company. The Grain Belt

logo was well-recognized: an orange diamond-shape with white, bold lettering,

and a bottle cap rendering in the background.

The Grain Belt Brew House, designed by nationally renowned brewery architects

Frederick Wolff and William Lehle, is part of a larger, 14-acre complex

that comprised the Brew House, which included a boiler house, a German-style

tavern, a warehouse of large grain bins, a bottling house, and an office.

The name refers to the "Grain Belt" of the American Midwest

where much of the world's supply of soybeans and grain is produced. Grain

Belt beer was popular in the upper Midwest from its inception well

into the 1960s and came in amber glass bottles and cans, becoming the

flagship brand of the Minneapolis Brewing Company. The Grain Belt

logo was well-recognized: an orange diamond-shape with white, bold lettering,

and a bottle cap rendering in the background.

But the marvelous structure eventually fell into decay. The Grain Belt Brew House remained in continuous operation as part of the Storz Brewing Company of Omaha from 1967 to 1975, but when Storz closed on Christmas Day of that last year, the Grain Belt Brew House ceased operations. The building stood empty and deteriorating, and the majority of its contents were sold or scrapped. In 1986, the City of Minneapolis stepped in and established the Grain Belt Brewery Redevelopment Project. Three years later, it bought the complex, stabilized the property with the intent of selling it to a developer interested in its restoration, and, in 2000, sold the Brew House to Minneapolis-based Ryan Companies for office space reuse.

RSP Architects, who actually began considering the Brew House one year

earlier for its new corporate headquarters, partnered with Ryan Companies

on the Brew House redesign. Both firms contributed to the cost and received

additional funding from the City of Minneapolis. The ball was rolling,

an end to a 25-year period of unsuccessful plans that mostly proposed

to gut the building.

RSP Architects, who actually began considering the Brew House one year

earlier for its new corporate headquarters, partnered with Ryan Companies

on the Brew House redesign. Both firms contributed to the cost and received

additional funding from the City of Minneapolis. The ball was rolling,

an end to a 25-year period of unsuccessful plans that mostly proposed

to gut the building.

A $20 million, two-year redesign was completed in 2002, transforming the once dilapidating beer factory into an airy, state-of-the-art, 21st-century office building, now home to 200 RSP Architects employees. The project has been recognized with an Honor Award from the AIA Minnesota, and an award from the Preservation Alliance of Minnesota. In addition to RSP, the 2005 National Trust Honor Award recognizes Ryan Companies; Minneapolis-based Hess, Roise and Company, a historical consultant firm; and the Community Planning and Economic Development Department (CPED) of the City of Minneapolis.

Renovation on tap

Renovation on tap

Judy Cedar was the senior project coordinator of the Brew House renovation

for the City of Minneapolis. Cedar stresses that the historic preservation

and adaptive reuse of the Brew House was a group effort. “The

City of Minneapolis benefited by having a world-class architecture

firm and construction company tackling all the issues related to the

preservation, rehabilitation, and reuse of the Brew House,” says

Cedar. “Partnership defined the success of this project.” But

turning a deteriorating Brew House into a stimulating and functioning

office environment was a challenge. The brewing process and exposure

to the elements had taken its toll on the structure, and extensive

testing revealed many elements needed augmentation, replacement, or

repair. “Construction challenges did abound,” Cedar says. “For

example, the building needed structural reinforcement in some areas.

And without successful abatement of mold, occupancy of the structure

would have been impossible.”

It was also important to maintain and celebrate the original architecture of the old structure as a local historic landmark, thus enabling it to qualify for federal tax credits, especially given its industrial location in an area called Sheridan, which, seven years ago, had very little office or retail space nearby and no redevelopment in progress.

Architectural historian Charlene Roise, president of Hess, Roise and

Company, worked on the project as a historical consultant, helping get

the historic investment tax credits that were an important piece in the

financing. She also nominated the project for the National Trust award,

which she believes it richly deserves. “I had almost given the

Grain Belt Brew House up for lost, having toured the deteriorating property

several times during the decades that it was abandoned,” Roise

says. “Developers came and went, all defeated by a structure specifically

designed to brew beer—and not at all accommodating to a new use.

Architectural historian Charlene Roise, president of Hess, Roise and

Company, worked on the project as a historical consultant, helping get

the historic investment tax credits that were an important piece in the

financing. She also nominated the project for the National Trust award,

which she believes it richly deserves. “I had almost given the

Grain Belt Brew House up for lost, having toured the deteriorating property

several times during the decades that it was abandoned,” Roise

says. “Developers came and went, all defeated by a structure specifically

designed to brew beer—and not at all accommodating to a new use.

Thankfully, the creative “dream team” of Ryan Companies and RSP Architects came along. RSP figured out how to make the space work, while being sensitive to the building’s historic character. Ryan had the financial savvy and the construction know-how to bring RSP’s plans to reality.”

Ryan eventually secured a "modified high-rise" designation for the building, even though only one section fits high-rise criteria, and the company continued to negotiate code exceptions during design and construction on a case-by-case basis.

New light through an old exterior

New light through an old exterior

Renovating the exterior of the building offered several challenges for

the dream team. While the east façade had massive arches and

windows, the north façade—the warehouse area of the building—had

few existing windows, only windows and arches expressed via a relief

pattern. This was meant to keep air inside the warehouse to cure and

store beer better. Thus, little natural light entered the warehouse

area. Preservation authorities approved cutting 72 new openings and

installing framed windows with glass where such openings had been "architecturally

defined." On secondary facades, new windows were installed in

a pattern sympathetic to the established fenestration. This required

sawing through masonry walls that were two feet thick and modifying

the structural-beam bearing points. Overall, 214 exterior windows were

added or replaced, dramatically increasing daylight throughout all

levels of the Brew House and providing views to the outside.

The north tower of the Brew House had suffered significant deterioration, but of course was important to preserve. To fix the tower, architects worked with engineers and construction consultants to implement basement-to-roof shoring, reinforcing the cross-bracing of supporting columns. An iron-railed, wooden widow's walk needed to be replaced, and the weathervane atop one of the towers cleaned and polished. Exterior murals of advertising art that were found when moldy plaster was removed were cleaned but not repainted. The existing stone porte-cochere arch was modified to create a portal connecting the street facade with quieter areas of the site.

Creating a workable interior

Creating a workable interior

To refurbish the inside, RSP architects worked with engineers to develop

creative ways to make office space from a layout originally designed

for a gravity-fed brewing process. The brick warehouse floors were

sloped and unevenly matched to allow drainage from leaking beer kegs

and fluids used to wash down storage areas. To address circulation

and space issues, the design team inserted a raised, level floor system

that also provided space underneath for routing electrical power and

voice and data systems. A mezzanine level was added between the first

two levels, and major sections of the Brew House became connected with

two timber-floor catwalks anchored by three elevators—one in

a former grain bin—at the north and south ends. “Creative

designs, including placement of elevators and catwalks, added interest

and function to the spaces,” Cedar points out. Meanwhile, the

entire fourth-level floor structure was in such disrepair it needed

to be lifted and completely replaced. In the end, 47 engineered wall

penetrations were made to increase horizontal and vertical circulation

paths and create doorways and openings.

Other challenges arose as the architects had to work around existing cast-iron columns to create a contemporary workplace. The column spacing was too tight to permit an even distribution of standard 8' x 8' work stations. The design team creatively weaved together private and shared work areas around the columns. The mezzanine helped to expand the openness for workstations, offices, and conference rooms.

Next, the interior design needed to address a four-story ornamental

iron staircase located in the atrium once used to reach beer tanks at

the top of the gravity-based brewing system. The staircase was disassembled,

and broken pieces reconstructed, adding a top rail to meet current building

code requirements. After priming and painting it on site, the staircase

was reconfigured, and then reinstalled to reach the new mezzanine. The

new stairway now smoothly provides circulation between work spaces, conference

rooms, and offices, some of which are above the exterior porte cochere.

Next, the interior design needed to address a four-story ornamental

iron staircase located in the atrium once used to reach beer tanks at

the top of the gravity-based brewing system. The staircase was disassembled,

and broken pieces reconstructed, adding a top rail to meet current building

code requirements. After priming and painting it on site, the staircase

was reconfigured, and then reinstalled to reach the new mezzanine. The

new stairway now smoothly provides circulation between work spaces, conference

rooms, and offices, some of which are above the exterior porte cochere.

The interior paint complements the existing Chaska brick, but in some areas new wall surfaces and existing columns were painted white to further boost brightness. Interior floor finishes vary from slate tile in the entry areas, to timber on the catwalks and in the main lobby, to carpet on the mezzanine. To accommodate mechanical, electrical, plumbing, and sprinkler systems, thousands of penetrations were made in the building’s thick masonry walls and ceiling. Curved portions of the interior structure that once supported brew tanks also remain in two locations, pointing out the original function of the building.

A catalyst for more development and preservation

A catalyst for more development and preservation

The Brew House was ready for occupancy less than 16 months after construction

began when, in March 2002, RSP moved approximately 200 architects,

interior designers, facility experts, and related staff from the three

buildings it had occupied in the Minneapolis’ Warehouse District

to the renovated Brew House. The old brewery tavern also has been converted.

It is now the Pierre Bottineau Community Library, a branch of the Minneapolis

Public Library system.

The redevelopment of the Grain Belt Brew House is serving as a catalyst for new office, restaurant, and residential development in its neighborhood, as well as new preservation projects in the area. The city has approved plans for residential and limited commercial development across the street and around the corner from the Brew House. Local nonprofit organizations also are exploring proposals to convert Grain Brew’s adjacent warehouse and bottling house into affordable living and studio spaces for artists.

“The Grain Belt Brew House preservation project is the catalyst that has made possible additional historic preservation of other historic structures within the Minneapolis Brewing Company Historic District,” notes Cedar. Roise believes the Grain Belt Brew House building is now an asset to northeast Minneapolis, and to the city as a whole. “In fact, the National Trust is holding its annual preservation conference in the Twin Cities in 2007, and I know that the Grain Belt Brew House will be a highlight for many visitors!”

“Receiving the National Historic Trust’s Honor Award is truly a crowning achievement. This award recognizes more than design excellence and quality craftsmanship: It honors the positive impact that our building renovation has had on its community,” concludes RSP Architects President Dave Norback, AIA. “RSP is pleased the Grain Belt Brewhouse Renovation has contributed to the Upper Mississippi River Renaissance and the continued revitalization of Northeast Minneapolis.”

Copyright 2006 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()

Did you know . . .

• “Brew” derives from the Indo-European root word meaning "bubble."

• Prohibition forced the Minneapolis Brewing Company to stop beer production from 1920 until 1933. The company temporarily changed its name to Golden Grain Juice Company and, like many other brewers, turned to making “near beer” and soft drinks.

• Because of World War II rationing, the company briefly had to resort to using cheaper, green glass bottles rather than the standard amber color.

• Grain Belt Beer is still brewed. In 2002, August Schell Brewing Company of New Ulm, Minn., reclaimed the Grain Belt heritage when it received its rights at a “moving party” on the grounds of Grain Belt Brew House. With a few hundred people looking on, the original recipe was inserted into a keg, sealed up, and transferred to New Ulm.

• The brewing process begins when bushels of barley malt (germinated barley) are mashed and a sweet liquid called wort extracted. The wort is boiled and hops added. Once cooled to 55 degrees, yeast is added to ferment the sugars, and beer is the result.

• Archeological evidence shows that brewing beer dates back to ancient Egypt.

Photos © 2002, George Heinrich. Courtesy of RSP Architects.

![]()