A New Globe in a New World

Will the British return to establish a beachhead of Anglophile culture in New York City?

by Zach Mortice

Assistant Editor

How Do You . . . integrate an updated version of Shakespeare’s Globe Theater into a 19th century naval base castle?

Summary: Foster + Partners’ design for a new Shakespearian Globe Theater places the auditorium in the circular courtyard of Castle Williams, an early 19th century military base. Instead of precisely recreating the Globe, the firm’s design takes it into the modern world of theater. The proposal is part of a new effort to redesign and develop all of Governor’s Island in New York.

There’s enough irony to fuel a Shakespearian drama in Barbara Romer’s proposal to build a new Globe Theater on little-used Governor’s

Island in New York. This Anglophilic icon has been designed by London-based

architects inside the stone ramparts of Castle Williams, built before

the War of 1812 to defend against encroaching Britons. Though project

architect Michael Wurzel calls it “one of the finest examples of coastal fortification in the United States,” its guns, ironically, never fired a shot. There’s enough irony to fuel a Shakespearian drama in Barbara Romer’s proposal to build a new Globe Theater on little-used Governor’s

Island in New York. This Anglophilic icon has been designed by London-based

architects inside the stone ramparts of Castle Williams, built before

the War of 1812 to defend against encroaching Britons. Though project

architect Michael Wurzel calls it “one of the finest examples of coastal fortification in the United States,” its guns, ironically, never fired a shot.

Despite these conceptual hijinks, Romer’s proposal is a serious one, and she’s drafted an international titan in historical renovation for her quest. Foster + Partners portfolio contains renovations to the Reichstag, the British Museum, the Hearst Building, and now, thanks to Romer’s cold calls and persistence, perhaps the New Globe. Wurzel says Lord Foster’s firm was bowed by the strength of Romer’s ideas and her willingness to express them. To get the ball rolling, she showed up in Foster’s office unannounced (he was out of the country at the time; she came back later) and convinced them to work on an initial model pro bono. “She can be very persuasive,” says Wurzel.

“I think what I’m good at is identifying the people who know best,” says Romer. “[Norman Foster is] somebody who has taken internationally historic structures and reimagined them and given them a new life and new heart.” Romer

(a former globe-trotting theater manager and director) is well-connected

and has assembled a star-studded group of actors, theater directors,

playwrights, and politicians to sign on their support for the theater. “I think what I’m good at is identifying the people who know best,” says Romer. “[Norman Foster is] somebody who has taken internationally historic structures and reimagined them and given them a new life and new heart.” Romer

(a former globe-trotting theater manager and director) is well-connected

and has assembled a star-studded group of actors, theater directors,

playwrights, and politicians to sign on their support for the theater.

Discovering New York

The site for the New Globe is probably the last bit of land anywhere near Manhattan that could be called undeveloped. From the colonial era to 1966, Governor’s Island was a naval military base. The Coast Guard assumed ownership until 2003, when New York City purchased it. The 172-acre island is half a mile from the southern tip of Manhattan, offers stunning views of the downtown skyline and the Statue of Liberty, and contains several historic structures. But it’s never been effectively developed or marketed as a tourist destination. “This is a part of New York we didn’t know before,” says Wurzel.

Foster + Partners isn’t the only firm becoming acquainted with Governor’s Island. The Governor’s Island Preservation and Education Committee is hosting a design competition that drew entrants from 29 teams of architecture firms. The remaining 22 acres that make up Castle Williams and Fort Jay is under the jurisdiction of the National Park Service, which is also in the midst of evaluating redevelopment plans. These plans will be opened to the public this summer or fall. Darren Boch, a Parks Service spokesperson, says the public’s input will help determine which plans are selected, but the Park Service will have the greatest say in the future of the site. Foster + Partners isn’t the only firm becoming acquainted with Governor’s Island. The Governor’s Island Preservation and Education Committee is hosting a design competition that drew entrants from 29 teams of architecture firms. The remaining 22 acres that make up Castle Williams and Fort Jay is under the jurisdiction of the National Park Service, which is also in the midst of evaluating redevelopment plans. These plans will be opened to the public this summer or fall. Darren Boch, a Parks Service spokesperson, says the public’s input will help determine which plans are selected, but the Park Service will have the greatest say in the future of the site.

Then, as now

Foster + Partner’s design fuses a 21st century update of the high-water mark of Elizabethan culture to a symbol of post-colonial independence. The century-spanning project is unique to Globe restorations all over the world, which have generally hewed narrowly to the Bard’s original stage. The apotheosis of this is the rebuilt Globe, which lies 200 yards from the original site of Shakespeare’s Globe on the south bank of the Thames.

“In London, they recreated 1599,” says Romer. “What I was intrigued with was what an American 21st century, cutting-edge Globe would be like. We want to be inspired by the Globe of London, but we want to cull the best of the experience.” “In London, they recreated 1599,” says Romer. “What I was intrigued with was what an American 21st century, cutting-edge Globe would be like. We want to be inspired by the Globe of London, but we want to cull the best of the experience.”

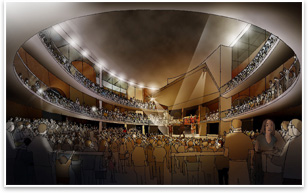

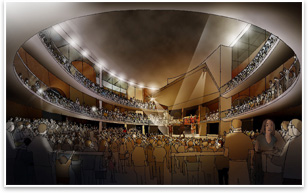

Romer says the most important “core truth” worth culling is the intimate and democratic relationship between the audience and actor. As a PhD student at Cambridge, Romer had admired the populism of the London Globe. Then, as now, theater at the Globe was for all—bawdy, broad, and affordable, with hundred of seamless groundlings at the actors’ feet. Foster’s design retains this populism, with a thrust stage that brings the action into patrons’ laps, and balconies that wrap all the way around the circular 1,200-person auditorium and stack everyone close to the stage. Exacting acoustical engineering, better lines of sight, and LEED® Gold certification bring the Globe into the modern world, and Foster’s initial designs are a very measured, conservative increase in the scale of the original.

Perhaps the last irony surrounding the New Globe is just how well all the pieces fit together. Though designed over 200 years apart from each other, the 90-foot diameter theater plops into the courtyard of the 120-foot diameter Castle Williams’s courtyard with ease. The theater proposal itself is a preservation strategy for the endangered castle. It’s completely reversible and encourages visitors’ patronage and support. The auditorium is sheathed in glass to give visitors a spatial sense of where they are within the castle’s stone walls. Perhaps the last irony surrounding the New Globe is just how well all the pieces fit together. Though designed over 200 years apart from each other, the 90-foot diameter theater plops into the courtyard of the 120-foot diameter Castle Williams’s courtyard with ease. The theater proposal itself is a preservation strategy for the endangered castle. It’s completely reversible and encourages visitors’ patronage and support. The auditorium is sheathed in glass to give visitors a spatial sense of where they are within the castle’s stone walls.

Thinking globally

The Foster + Partners design is informed by deep research into theater history and culture, and Romer considered theater design traditions from all over the world as she formed her vision of the New Globe. Both have made it clear that the design is no slave to history, but what Romer and Wurzel need most is for the New Globe to be a convincing uniting of the cultural capitals of Elizabethan London and 21st century New York. |