| Converging Technologies

Summary: While we tend to think of building information modeling (BIM) as the “core of the revolution” in design technology, there are other, related technologies with the potential to change significantly the way buildings are designed and constructed, and that, in turn, may have a significant impact on decisions that building owners make about the built environment.

Conceptually, 3D laser scanning is as simple as it sounds. A 3D laser scanner is placed in the center of an interior space and scans the interior surfaces with a laser beam, generating a three-dimensional “point cloud” data file that can then be converted to 2D CAD, 3D BIM, or even black and white photographic images. The technology is equally useful for documenting building exteriors as well as interior spaces that might be too small to be physically accessible or may contain hazardous materials, such as interstitial spaces with asbestos insulation. Most often cited for documenting historic structures with a high level of exterior or interior architectural detail, 3D laser scanning can be used to document any existing building of any age and style for which accurate existing condition documentation is needed.

“These projects have brought us through a learning curve,” notes firm principal Tom Johnson, AIA. “I was slow to convert to laser scanning. The typical owner/architect contract requires the owner to provide base building information, but the reality of rehabilitation projects is that architects usually do it. Laser scanning provides us with the highest quality of base building information.” The firm plans to follow the model of other firms that have made the CAD-to-BIM transition successfully by choosing a new project to serve as a BIM pilot, which can then be analyzed to tailor new BIM design and business processes to the firm’s specialized work. “We’ve been sending staff to training in waves,” says Johnson. “The next project that goes into production, we’ll be ready for BIM.”

The firm’s experience has caught the attention of the Office of the Chief Architect of the U.S. General Services Administration, a building owner with a greater-than-typical need for accurate documentation of existing buildings. The firm is currently working on a GSA project involving the restoration/rehabilitation of the federal courthouse in Brooklyn, N.Y. “There are a number of ways to measure existing buildings,” says Johnson. “When we responded to the GSA RFP, we were the first firm they had seen that had been using laser scanning for so long.” Copyright 2007 Michael Tardif |

||

Copyright 2007 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› One Hundred Percent BIM

› FOX Architects Takes the Plunge

› BIM 2011: A Five-year Forecast

Michael Tardif, Assoc. AIA, Hon. SDA is a freelance writer and editor in Bethesda, Md., and the former director of the AIA Center for Technology and Practice Management.

Captions:

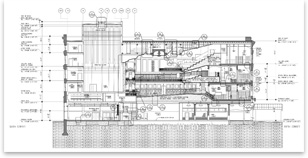

Image 1: Opera House Building Section, Mississippi State University Riley Center for Education and the Performing Arts by Martinez & Johnson. This scaled building section in AutoCAD is a product of the laser-scanning subcontractor measuring service, and was used as an existing conditions base drawing for architectural design that included a new stage house, trap level, and interior restoration. Photo courtesy Martinez & Johnson.

Image 2: Q-View, Mississippi State University Riley Center for Education and the Performing Arts by Martinez & Johnson. This black and white image of the audience chamber is not a photograph; it was generated from the “cloud point data” taken by a laser-scanning device. Photo courtesy Martinez & Johnson.

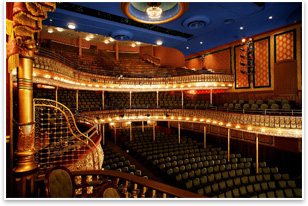

Image 3: Opera House, Mississippi State University Riley Center for Education and the Performing Arts by Martinez & Johnson. The completed audience chamber of the Opera House of the Riley Center for Education and the Performing Arts. Photo © Whitney Cox.