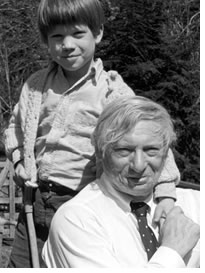

An Interview With My

Architect Film Maker

Nathaniel Kahn

Lou Kahn’s son talks about his movie

and getting to know about his

dad and architecture

The

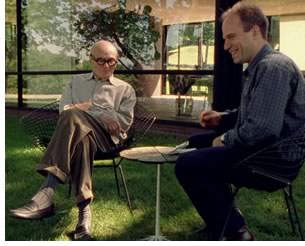

week before Nathaniel Kahn will hold a special question-and-answer session

in conjunction with the June 11 screening of his film, My

Architect: A Son’s Journey, at the AIA national convention

in Chicago, he talked with AIArchitect

Executive Editor Douglas E. Gordon, Hon. AIA. Kahn details similarities

between film making and creating a building and describes how his journey

expanded his understanding of his father, his father’s architecture,

and the ability of architecture to make a difference.

The

week before Nathaniel Kahn will hold a special question-and-answer session

in conjunction with the June 11 screening of his film, My

Architect: A Son’s Journey, at the AIA national convention

in Chicago, he talked with AIArchitect

Executive Editor Douglas E. Gordon, Hon. AIA. Kahn details similarities

between film making and creating a building and describes how his journey

expanded his understanding of his father, his father’s architecture,

and the ability of architecture to make a difference.

How did the research you did for this

movie sharpen your appreciation of architecture?

I think that until I picked up a movie camera and tried to capture the

feeling, look, and nature of my father’s buildings, I hadn’t

slowed down enough to figure them out. The analogy that comes to mind

is that architects—wherever they are in the world—want to

draw a building when they see it. I felt the same way about filming the

buildings, in the sense that when you draw something, you’re forced

to slow down and really observe how it’s made, what’s holding

up what, and the proportions. You have to take notice of what makes it

what it is. That same thing is true for me in trying to find ways of filming

my father’s buildings that really captures their essence.

I

wasn’t just interested in how they looked, but also in how they

made me feel. That meant going back to the buildings a number of times

and filming them in different weather conditions and times of day. It

gave me a sense of the concept that architecture lasts a long time and

people don’t. It’s very wonderful that architecture really

is an art that deals with time. A really good building makes you very

aware of time, our own ephemeral-ness and the fact that the things that

we make can last a lot longer.

I

wasn’t just interested in how they looked, but also in how they

made me feel. That meant going back to the buildings a number of times

and filming them in different weather conditions and times of day. It

gave me a sense of the concept that architecture lasts a long time and

people don’t. It’s very wonderful that architecture really

is an art that deals with time. A really good building makes you very

aware of time, our own ephemeral-ness and the fact that the things that

we make can last a lot longer.

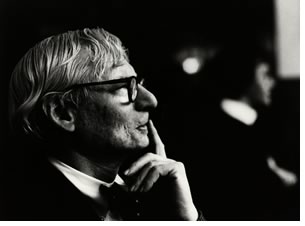

The place in history—for instance, Lou’s work in India and Bangladesh—is an idea I had not expected to find. Lou certainly was thought of as an architect in the heroic mode; he was interested in making the world a better place and changing the way we live in and view the world. In some degree, in America, that might have been thought of as being a little bit idealistic. Then to see what Lou was able to achieve in India and Bangladesh—what his architecture is able to do—was astonishing. Somehow, that building and that complex actually did make a difference to those people and did help a fledgling democracy to find its way. It was very moving to me that the building did change the world for those people.

How

did getting an appreciation for your father’s work let you know

the person?

How

did getting an appreciation for your father’s work let you know

the person?

I was surprised at how many different aspects of his personality are in

his buildings. I always knew there was the solemnity, monumentality, and

power—all that stuff I expected to find. But I was surprised to

find other aspects of him—the playfulness, fun, and romanticism.

That was a real joy. I hope that the film helps people see those things

not only in his architecture, but also in the architecture that surrounds

them every day.

I

made the film not for architects but for the general public. Of course,

I hoped and expected to grab the architecture audience, but I really wanted

to make something that would appeal to a much broader, general audience.

And, of course, the way to do that is to tell a good story and make something

that is emotionally compelling—an emotional story—rather than

something that just engages your intellect.

I

made the film not for architects but for the general public. Of course,

I hoped and expected to grab the architecture audience, but I really wanted

to make something that would appeal to a much broader, general audience.

And, of course, the way to do that is to tell a good story and make something

that is emotionally compelling—an emotional story—rather than

something that just engages your intellect.

The task that I set for myself was to make the architecture emotional and have it be something that would convey the various aspects of the person who created it, and—to go beyond that—be something that talks about architecture and its power in general. That matters a lot to me. I’ve always felt that intuitively, and I’ve certainly been told that by any architect I’d run into. But it wasn’t until I made this film that I really realized it’s true. What architects do really can change the world and make a difference for people. It’s fundamental, just as with that wonderful Churchill quotation: “First we shape our architecture. Thereafter, it shapes us.” I certainly found that in making this film.

I

know what architects do is a struggle, just like film making. It’s

extremely difficult. Frank Gehry said something really wonderful that

isn’t in the film, but I’ve thought about a lot of times since

then. He said that in making a building, so many things transpire to make

it less than what you dreamed of—whether it’s problems with

money, time, materials, or with people liking it; any number of things.

Yet, sometimes things happen, things get through, and buildings get made.

Films are very much like buildings that way. A lot of things—a lot

of the same things—transpire along the way to make it less than

what you’d hoped. But once in a while, things happen and a really

good thing comes out, and you sense that it is kind of a miracle. Making

this film gave me the sense of how much architects really have to go through

to get something done and how difficult it is. It does make you see a

building—when it really turns out well—as magic.

I

know what architects do is a struggle, just like film making. It’s

extremely difficult. Frank Gehry said something really wonderful that

isn’t in the film, but I’ve thought about a lot of times since

then. He said that in making a building, so many things transpire to make

it less than what you dreamed of—whether it’s problems with

money, time, materials, or with people liking it; any number of things.

Yet, sometimes things happen, things get through, and buildings get made.

Films are very much like buildings that way. A lot of things—a lot

of the same things—transpire along the way to make it less than

what you’d hoped. But once in a while, things happen and a really

good thing comes out, and you sense that it is kind of a miracle. Making

this film gave me the sense of how much architects really have to go through

to get something done and how difficult it is. It does make you see a

building—when it really turns out well—as magic.

One

of the things that really surprised me about my father, and one of the

areas I’m most happy about in the film, is where we talk about all

the projects he designed that were not built; that symphony of images

that didn’t happen for one reason or another. One of the things

that really gets me about them and endears him enormously to me is how

much he kept at it and wouldn’t give up. If one thing fell through

for him, then, well, he knew something else will come through the next

day. That’s a phenomenal attitude. All of us complain if something

doesn’t work out. I’m sure he did, too, but he wouldn’t

let that get him down for long. That was an aspect of him that I wasn’t

as familiar with, and it was really wonderful to discover.

One

of the things that really surprised me about my father, and one of the

areas I’m most happy about in the film, is where we talk about all

the projects he designed that were not built; that symphony of images

that didn’t happen for one reason or another. One of the things

that really gets me about them and endears him enormously to me is how

much he kept at it and wouldn’t give up. If one thing fell through

for him, then, well, he knew something else will come through the next

day. That’s a phenomenal attitude. All of us complain if something

doesn’t work out. I’m sure he did, too, but he wouldn’t

let that get him down for long. That was an aspect of him that I wasn’t

as familiar with, and it was really wonderful to discover.

Do

you ever have the experience of looking in the mirror and seeing your

father?

Do

you ever have the experience of looking in the mirror and seeing your

father?

There are certain similarities. Like him, I’m a little slow—things

take me a long time to get done. Aside from that, I hope that I have some

of him in me—he had a lot of amazing qualities. People have said

once in a while that I walk a little bit like him. I like to think of

that, because it must be from inside. He wasn’t around long enough

for me to learn to imitate the way he walked.

If you could ask any questions of your

father now, what would you ask?

I’d hate to disappoint you on this question. But when I started

out on this film, I had many questions. Since making this film, at this

point, I wouldn’t want to ask him any questions. That’s part

of what the film’s process was for me: beginning with so many questions,

ending with many of the same ones, but really wanting to know the guy

and spend some time with him. Sitting in one of those joints in Philadelphia

that he loved so well and sharing a Rolling Rock, which was the beer that

he preferred. Just father to son.

Copyright 2004 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()

|

||

| For more

information about the screening of My Architect at the AIA Convention

in Chicago June 10, 7–10:30 p.m. at the Adler Sullivan-designed

Auditorium Theatre, go to the AIA Convention site. You will see a convention registration icon in the upper right-hand corner of that page through which you can also register for tickets to the screening. If you are already registered for the convention, you can go to your personal URL, which came with your registration confirmation, and add ticket E51 to your itinerary. Tickets will also be available June 8–10 at the AIA Bookstore and Convention Registration booth on site at Chicago’s McCormick Place. Click here for the AIArchitect review of My Architect. Metropolis magazine

also interviewed Nathaniel Kahn for its June 2003 issue. And there is a My Architect Web site.

|

||