You Have to See This

Movie!

Nathaniel Kahn’s My

Architect: A Son’s Journey

details his poignant search for his father, Louis. I. Kahn

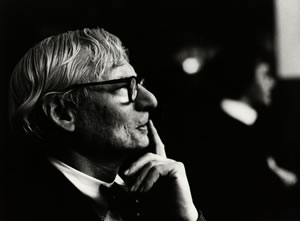

Anyone

with any connection to architecture in the latter half of the last century

knows of Louis I. Kahn: genius and creator of some of the best-known and

most-admired buildings of the time and beloved professor of architecture

at Yale and the University of Pennsylvania. He talked to bricks, and they

answered him truly. An Estonian immigrant whose face and hands had been

scarred by a burning coal when he was a child, he emigrated to America

at the age of three, and grew up to be the husband of Esther and the father

of Sue Ann. Most also know that he died on a return trip from India, alone

in New York’s Penn Station men’s room in 1974, and that his

body lay unclaimed for days. Most don’t know that Kahn had crossed

out the address on his passport, making identification difficult. Why?

Anyone

with any connection to architecture in the latter half of the last century

knows of Louis I. Kahn: genius and creator of some of the best-known and

most-admired buildings of the time and beloved professor of architecture

at Yale and the University of Pennsylvania. He talked to bricks, and they

answered him truly. An Estonian immigrant whose face and hands had been

scarred by a burning coal when he was a child, he emigrated to America

at the age of three, and grew up to be the husband of Esther and the father

of Sue Ann. Most also know that he died on a return trip from India, alone

in New York’s Penn Station men’s room in 1974, and that his

body lay unclaimed for days. Most don’t know that Kahn had crossed

out the address on his passport, making identification difficult. Why?

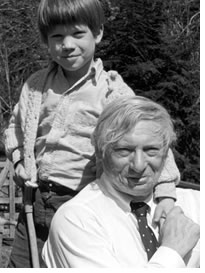

The unsolved mystery proved a minor adjunct to the larger mysteries of Kahn’s life. He had three families in Philadelphia: besides Esther and Sue Ann, there were Anne Tyng, FAIA, and their daughter, Alexandra Tyng, and Harriet Pattison and their son, Nathaniel, who was 11 when his dad passed away. The three families, all of whom lived within a radius of a few miles, met for the first time at Louis Kahn’s funeral.

Nathaniel

Kahn recalls his famous father from his once-a-week visits to their home

as well as Nathaniel’s visits to his dad’s office, where his

mother was employed. For a quarter of a century, Nathaniel lived with

fond memories of his dad’s great stories of “silly boats”

(they handmade a little book about them together) and of faraway places,

like India. Then Nathaniel needed more: A filmmaker by profession, he

set out on a five-year odyssey to find the father he barely knew. He did

it through Louis Kahn’s architecture and the people who understood

it—and him—best. The resulting two-hour movie, My

Architect: A Son’s Journey, is nothing short of spellbinding.

Nathaniel

Kahn recalls his famous father from his once-a-week visits to their home

as well as Nathaniel’s visits to his dad’s office, where his

mother was employed. For a quarter of a century, Nathaniel lived with

fond memories of his dad’s great stories of “silly boats”

(they handmade a little book about them together) and of faraway places,

like India. Then Nathaniel needed more: A filmmaker by profession, he

set out on a five-year odyssey to find the father he barely knew. He did

it through Louis Kahn’s architecture and the people who understood

it—and him—best. The resulting two-hour movie, My

Architect: A Son’s Journey, is nothing short of spellbinding.

Cast

of characters

Cast

of characters

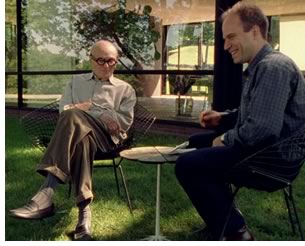

Nathaniel’s players are a contemporary architecture’s Who’s

Who, from the ever-gracious I. M. Pei to nonagenarian King of Urban

Renewal Edmund Bacon, yelling on a Philadelphia street corner in all his

cantankerous glory. While Pei gently tells Nathaniel, “Three or

four masterpieces are better than 50 or 60 buildings,” Bacon loudly

insists that Kahn pere never really

understood what the overall remake of Philadelphia in the ’60s was

about, and that Kahn fils is just

as dense. Cameos by Philip Johnson, FAIA; Robert A.M Stern, FAIA; and

Frank Gehry, FAIA, add facets to Louis Kahn the Architect, the Genius,

the True Artist. A walk through the desert in Israel with Moshe Safdie,

FAIA, adds incredible depth to the understanding of Louis Kahn as “the

nomad,” which indeed is the name of that particular sequence of

the film.

Two

other architects, the mothers of Kahn’s two younger children, bring

important understanding to the film: Anne Tyng, FAIA, and landscape architect

Harriet Pattison, Nathaniel’s mother. That they both became architects

when women architects still were a rarity speaks immediately to their

courage; ditto their single motherhoods. That each worked with Louis Kahn

when they were romantically involved with him speaks of the intermingling

love for the man, the architect, and the architecture. Both Tyng and Pattison

wanted different endings for their love stories, yet both still speak

about Kahn without bitterness.

Two

other architects, the mothers of Kahn’s two younger children, bring

important understanding to the film: Anne Tyng, FAIA, and landscape architect

Harriet Pattison, Nathaniel’s mother. That they both became architects

when women architects still were a rarity speaks immediately to their

courage; ditto their single motherhoods. That each worked with Louis Kahn

when they were romantically involved with him speaks of the intermingling

love for the man, the architect, and the architecture. Both Tyng and Pattison

wanted different endings for their love stories, yet both still speak

about Kahn without bitterness.

While he could

justify becoming angry, bitter, or permanently “wounded,”

Nathaniel also stays the course of his journey and transcends the hurt

of his largely absent father. He seasons his tale with interviews of non-architects,

bringing the level on which we see Louis a little closer to earth. He

talks to cab drivers who remember shuttling his father from family to

family and around his beloved Philadelphia. Talks with a pair of rabbis

and with his garrulous and WASPy aunts tell some of the anti-Semitism

his father must have encountered with Mainline Philadelphia. And, in a

heart-sinking moment, Nathaniel’s face crashes—quietly—when

a compadre who worked on the Salk Institute casually mentions that Lou

happily spent Christmas at his house with his kids. Nathaniel digests

this while rollerblading the length of the Institute’s famed and

solemn courtyard, skipping across the iconic central water element with

a little more deliberation than necessary. Yet in the end, he embraces

all that his father was.

While he could

justify becoming angry, bitter, or permanently “wounded,”

Nathaniel also stays the course of his journey and transcends the hurt

of his largely absent father. He seasons his tale with interviews of non-architects,

bringing the level on which we see Louis a little closer to earth. He

talks to cab drivers who remember shuttling his father from family to

family and around his beloved Philadelphia. Talks with a pair of rabbis

and with his garrulous and WASPy aunts tell some of the anti-Semitism

his father must have encountered with Mainline Philadelphia. And, in a

heart-sinking moment, Nathaniel’s face crashes—quietly—when

a compadre who worked on the Salk Institute casually mentions that Lou

happily spent Christmas at his house with his kids. Nathaniel digests

this while rollerblading the length of the Institute’s famed and

solemn courtyard, skipping across the iconic central water element with

a little more deliberation than necessary. Yet in the end, he embraces

all that his father was.

The

real stars of the film are Louis Kahn’s buildings, filmed in sequence

by someone who has come to know intimately and love the powers of stone

and space and light. Interspersed with the interviews, they start with

the Yale Art Gallery, Trenton Bathhouse (which Lou developed with Tyng),

and the Richards Medical Towers. They segue to a Modern building Who’s

Who: the Salk Institute for Biological Studies, Exeter Library,

Yale Center for British Art, and Kimbell Art Museum, each more masterful,

each more honed to the architect’s quest for timeless architecture.

Were My Architect solely a retrospective

of Louis Kahn’s work, it could stand on its own merit as a building

documentary.

The

real stars of the film are Louis Kahn’s buildings, filmed in sequence

by someone who has come to know intimately and love the powers of stone

and space and light. Interspersed with the interviews, they start with

the Yale Art Gallery, Trenton Bathhouse (which Lou developed with Tyng),

and the Richards Medical Towers. They segue to a Modern building Who’s

Who: the Salk Institute for Biological Studies, Exeter Library,

Yale Center for British Art, and Kimbell Art Museum, each more masterful,

each more honed to the architect’s quest for timeless architecture.

Were My Architect solely a retrospective

of Louis Kahn’s work, it could stand on its own merit as a building

documentary.

Redemption

The film is infinitely richer, though, for its layers of people stories.

Although we can rate and debate Louis Kahn the Architect’s oeuvre

until the sacred cows come home, judgment on Louis Kahn the Father remains

the province of Nathaniel and his sisters. It is hard to imagine, however,

any architectural heart not lightened by knowing that in the end Lou is

graced with Nathaniel’s acceptance through understanding of his

buildings. Understanding builds as Nathaniel travels through the Indian

Institute of Management in Ahmedabad (1962–1974) and speaks with

internationally honored architect and teacher B.V. Doshi, who worked with

his father.

Understanding

culminates at the Capital Complex at Dhaka (1962–1983), Bangladesh,

where native son Shamsul Wares with quiet passion explains to Nathaniel

how Louis, in creating this timeless masterpiece, gave democracy to Bangladeshis

as their government was being born. In the backdrop as silent witness,

light pours through massive concrete cutouts; acceptance dawns with the

light. It was here, not in Philadelphia, that Kahn found his own freedom

to build on the scale of which he previously had only dreamed.

Understanding

culminates at the Capital Complex at Dhaka (1962–1983), Bangladesh,

where native son Shamsul Wares with quiet passion explains to Nathaniel

how Louis, in creating this timeless masterpiece, gave democracy to Bangladeshis

as their government was being born. In the backdrop as silent witness,

light pours through massive concrete cutouts; acceptance dawns with the

light. It was here, not in Philadelphia, that Kahn found his own freedom

to build on the scale of which he previously had only dreamed.

Nathaniel’s film offers a multi-level love story. His search and subsequent acceptance of life’s slings and arrows tell a tale of love of self and one of filial respect beyond the required baseline. Anne Tyng and Harriet Pattison, great adventurers of their time, both lived a romantic alchemy of love for work and genius that perhaps evokes love of creation. And, not least, Nathaniel Kahn proves that filmmakers as well as architects can wield as a tool the love of space and light—timeless and beautifully documented in this extraordinary journey.

Copyright 2004 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()

|

||

| The national staff thanks McGraw-Hill Construction for bringing My Architect: A Son’s Journey to AIA headquarters. My Architect was just nominated for an Academy Award for Best Documentary [oscar.com]. Winners will be announced February 29. To learn more about the film, including show locations and times,

visit the My Architect

Web site.

|

||