by David Pearson

(University of California Press, in arrangement with Gaia Books, 2001)

Reviewed by Stephanie Stubbs, Assoc. AIA,

Managing Editor

Though

fascinatingly disparate in style, the buildings featured in New

Organic Architecture: The Breaking Wave share an overarching force;

they draw their life and their inspiration from nature. Author David Pearson

has given us a rich range of buildings through which to appreciate organic

architecture, as well as a detailed framework with which to study the

concepts behind it.

Though

fascinatingly disparate in style, the buildings featured in New

Organic Architecture: The Breaking Wave share an overarching force;

they draw their life and their inspiration from nature. Author David Pearson

has given us a rich range of buildings through which to appreciate organic

architecture, as well as a detailed framework with which to study the

concepts behind it.

The author considers the rectilinear architecture of our time to be "a reflection of the materialist values of an industrially driven age." The world is now waking up to an "older and wiser vision" of organic design, he says, which allows a new freedom in the creation of everything from lighting and textiles to architecture. Additionally, the effect of CAD on architecture today serves to "free up design and designers' creative processes." With the latest three-dimensional design software, it is much easier to design and model sophisticated and complex shapes and forms. Organic thinking, he says, is also an expression of the "femininization," or perhaps the rebalancing, of our overly masculine Western society.

Organic architecture is not a return to the past, a nostalgic style, Pearson warns, it has always fascinated and inspired. "Like a breaking wave, he says, "this new and exciting paradigm is sweeping over the world and transforming architecture and design for the 21st century."

Conceptual

framework

Conceptual

framework

The book works in two parts. The first is a conceptual reference section.

Using examples and explanations from practicing architects, it offers

eight themes of organic architecture:

Building as nature, which says the creative process of architecture starts from within, as with a "seed concept" that grows outward, ever-changing in form. This theme also embraces sustainable design and ecological architecture, and, as the author tells us, as scientists reveal more of the structure of nature, architects have an ever-increasing palette with which to design.

Continuous present, meaning the architecture is an ongoing event that is "beginning again and again," in the words of Bruce Goff. This Tao of design, the author explains, keeps the design fresh, just as it was employed by Antonio Gaudí on the continually evolving Sagrada Familia.

Form follows flow purports that a building should follow the flow of energy and be created by it. Architecture needs to work with the flow of natural energy—wind, water, structural forces, earth energy, "as well as the subtle human energies of body, mind, and spirit." Frank Lloyd Wright's Guggenheim Museum serves as illustration for this chapter.

Of the people means that organic design places special emphasis on the clients and the users of the building. The author quotes Canadian architect Douglas Cardinal's notion of "wrapping" a space around its function.

Of the hill draws from one of Wright's best known explanations of architecture, saying that a building should best be described as "of the hill" rather than "on the hill"; the building form should spring from the site. This theme also explains that the architect of today must also be concerned with making a minimal human impact on the environment and wildlife habitats.

Of

the materials simply means that the organic building takes it shape

from the materials of which it is built. Although traditional materials—earth,

wood, straw—have offered the traditional venue for organic architecture,

the author allows room for manufactured and new materials in organic design.

Materials today need to be healthy, ecologically sound, and resource-efficient,

he reminds us.

Of

the materials simply means that the organic building takes it shape

from the materials of which it is built. Although traditional materials—earth,

wood, straw—have offered the traditional venue for organic architecture,

the author allows room for manufactured and new materials in organic design.

Materials today need to be healthy, ecologically sound, and resource-efficient,

he reminds us.

Youthful and unexpected calls up the unexpected aspects of organic architecture. "Organic architects are often very individual characters," Pearson writes. "Some like to be maverick, provocative, and even anti-establishment." Renzo Piano, well represented throughout this book, puts is in a slightly more staid, yet still exciting way: "Each project is a new start, and you are in unexpected territory. You are a Robinson Crusoe of modern times."

Living music tells us that organic goes beyond frozen music to "seeing Nature as modern and ever new."

This

section of the book offers a look at the sources and inspirations for

organic architecture. They are as varied as the resulting building types,

and they all come from nature. The author starts with a fascinating essay

on the "ascendancy of geometry" and how our changing knowledge

of this field throughout history has always driven architecture. Many

familiar names—Wright, Goff, Gaudí—surface in this section.

Pearson also draws a distinction between organic architecture and the

so-labeled "deconstructivism" of Gehry, Hadid, Eisenman, and

Koolhaas. Although there are parallels between deconstructivism and organic

architecture, Pearson believes the two styles are driven by antipodal

forces: deconstructivism by a need to express a world of apprehension

and uncertainty; organic architect by a desire for a harmonious and sustainable

future.

This

section of the book offers a look at the sources and inspirations for

organic architecture. They are as varied as the resulting building types,

and they all come from nature. The author starts with a fascinating essay

on the "ascendancy of geometry" and how our changing knowledge

of this field throughout history has always driven architecture. Many

familiar names—Wright, Goff, Gaudí—surface in this section.

Pearson also draws a distinction between organic architecture and the

so-labeled "deconstructivism" of Gehry, Hadid, Eisenman, and

Koolhaas. Although there are parallels between deconstructivism and organic

architecture, Pearson believes the two styles are driven by antipodal

forces: deconstructivism by a need to express a world of apprehension

and uncertainty; organic architect by a desire for a harmonious and sustainable

future.

Living organic architecture

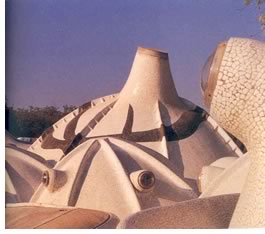

The second section of the book, "Living Organic Architecture"

is the "show me" part. It presents the work of 30 organic architects

from 15 countries, in photos, sketches, and their own words. They range

from the renowned to the obscure, and while most have lifelong careers

in organic architecture, some are just now branching into this field.

(Interestingly, the author bemoans the fact that most of the architects

featured are male, which is a reflection of the male-dominated design

profession as a whole. "It is only to be hoped that, not only will

more women join these professions, but that many of these will also become

talented organic designers.")

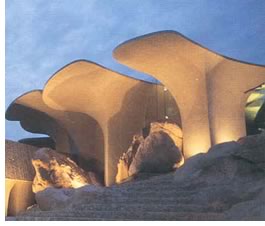

A

personal favorite in the wealth of beautiful color images is the sinuously

curved brick house Canadian architect Douglas Cardinal designed for himself.

In his essay on "Organic Process," Cardinal writes, "A

balance must be achieved between the external and internal elements which

shape the building, much like a tree which has its own genetic code but

which is also shaped by the natural forces acting upon it." Each

room is like a cell, with its own genetic code, and as relationships develop

among the cells, a matrix evolves that suggests the building design. When

the design is placed on the site, the natural elements shape the building

from the outside in.

A

personal favorite in the wealth of beautiful color images is the sinuously

curved brick house Canadian architect Douglas Cardinal designed for himself.

In his essay on "Organic Process," Cardinal writes, "A

balance must be achieved between the external and internal elements which

shape the building, much like a tree which has its own genetic code but

which is also shaped by the natural forces acting upon it." Each

room is like a cell, with its own genetic code, and as relationships develop

among the cells, a matrix evolves that suggests the building design. When

the design is placed on the site, the natural elements shape the building

from the outside in.

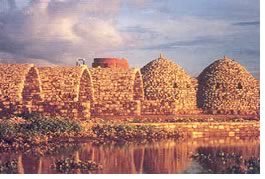

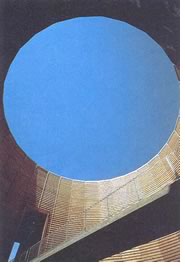

Fresh from being inspired by AIA 2002 Gold Medalist Tadao Ando, who spoke at the AIA national convention, it was particularly rewarding to further explore his work by reading his essay, "Wood Culture," in which he talks about the ideas that shaped development of the Museum of Wood, Hyogo, Japan. The museum, built to celebrate Japan's 45th National Tree Day, pays homage to wood pillar-and-beam construction, which supports a 60-foot-tall ring space with a pond in the middle. The museum also celebrates wood in its natural state: "The first consideration of this project was to avoid cutting the existing forest, whenever possible," Ando says. "The Museum, it was felt, should grow naturally in its site within the enclosing trees."

There are 28 more examples, all different, all worth a look.

Copyright 2002 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved.

![]()

|

To purchase New Organic Architecture: The Breaking Wave from the AIA Bookstore, ($31.50 AIA members/$35 nonmembers) phone 800-242-3837 option #4, fax 202-626-7519, or email. For articles about the AIA convention, including Ando's Gold Medal address, click here. |

|