by Tony

Wrenn

by Tony

Wrenn

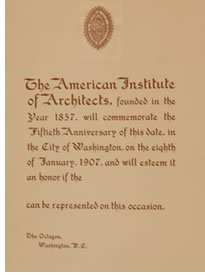

The AIA, born on February 23, would be 50 in 1907, and there would

be a party. The engraved invitations read “The American

Institute of Architects, founded in the year 1857, will commemorate

the Fiftieth Anniversary of this date, in the City of Washington,

on the eighth of January 1907, and will esteem it an honor if the

_______can be represented on this occasion.” To confuse one a

bit, the actual “commemorative exercises” were on January

9, beginning at the New Willard Hotel at 14th and Pennsylvania at

2:30 p.m., with greetings from architecture societies, art groups,

and universities around the world, and featured “addresses,

reminiscent and historical.”

The festivities concluded at the Octagon at 4:30 p.m., with a

reception and tea prepared by “patronesses” who were the

wives of members, or, in the case of AIA President Robert S.

Peabody, his daughter, Miss Peabody. An exhibition of the works of

Sir Aston Webb, who had the night before received the AIA’s

first Gold Medal, was on view, and Webb was present to talk with

birthday celebrants. During the evening, President Peabody unveiled

a bronze tablet “in honor of its founders and of those who

joined with them to Frame its Constitution and By-Laws.” There

were 13 names on the list of founders; 18 on the list of those who

joined with them. The birthday dinner followed “on the 10th

floor, New Willard, at 7:30 p.m.”

An early commemoration

Glenn Brown, the AIA secretary and treasurer, had penned a short

history of the AIA’s first 50 years in which he described

“noted” conventions and events and praised those who had

served as president. There had been but 10 presidents in those 50

years. He noted especially the successes of the Institute “in

the past seven years,” 1899–1907. “It initiated the

movement for systematic improvement of cities in this country;

secured the appointment of a Park Commission to report on the

development of Washington City; prevented the remodeling of the

White House and extension of the Capitol on lines which would have

destroyed their beauty; preserved the Mall, by demonstrating that

an improper location of the Agricultural Building would destroy the

future artistic development of the city . . . aided in the

establishment of the American Academy in Rome, a post-graduate

school in architecture painting, sculpture and music. . . gave in

1907 its first Gold Medal for distinguished merit in Architecture.

. . thus establishing a precedent which will be followed of

honoring those who have distinguished themselves in our

Art.”

Indeed, the

Gold Medal was the first award approved by the AIA, and it, and the

School Medal, authorized in 1914 and designed by Victor D. Brenner,

have stood the test of time, for both are still awarded.

Indeed, the

Gold Medal was the first award approved by the AIA, and it, and the

School Medal, authorized in 1914 and designed by Victor D. Brenner,

have stood the test of time, for both are still awarded.

The Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) had given its Gold

Medal both to AIA members Richard Morris Hunt and Charles F. McKim.

McKim, anxious to return the favor, suggested an AIA Gold Medal,

with Sir Aston Webb as the recipient. Webb had been president of

RIBA, and it was he who had awarded the medal to McKim in London.

The American Gold would be the highest honor the Institute could

award an architect.

The design of an American Gold Medal was given to sculptor Adolph

A. Weinman, whose work on the Wisconsin State Capitol and

Pennsylvania Station in New York, among others, was internationally

known. His design featured, on the obverse, the profiles of

Polygnotus, Ictinus, and Phidias, the architects and chief sculptor

of the Parthenon, and their tools: a brush, a sculptor’s

modeling tool, a compass, and a triangle. On the reverse an eagle

with upraised wings as if just landed or ready to fly away, plucks

a laurel branch from a rock. “AIA” and “A.A.

Weinman, M.C.M.VII.” are etched into the rock. The

recipient’s name, and the date awarded would, as is still the

custom, be engraved on the rim.

The 1907 and first such medal was awarded to Webb at a reception in

the Corcoran Gallery of Art on the evening of January 8. Since the

RIBA medal was awarded by the Crown, McKim initially suggested that

the AIA medal be awarded by the American president, but that idea

was vetoed by Theodore Roosevelt. He did not rule out his

participation in the award though, and, during Webb’s stay in

Washington, invited Webb to lunch at the White House.

In the Gold Medal presentation to Webb, AIA President Frank Miles

Day noted: “Matthew Arnold’s dictum that not only is good

work needed to put a poet in secure place, but a great body of good

work, is no less true of other arts than it is of poetry. On the

score of amplitude, your achievement lacks nothing, for no

architect in England, save Sir Christopher himself, has been

entrusted with the conduct of so many and such vast

works.”

Webb

responded, “I have come over here personally to say

‘Thank you’ in the sincerest and the directest and the

simplest way I can. And to assure you that all architects on the

other side of the water will deeply appreciate the fact that on

this, the jubilee day of your Institute, and the institution of

this gold medal, you should send it over to the other side ... It

has always been one of my happiest recollections that it fell to my

lot to have the privilege to hand our medal to Mr. McKim.

(Applause) He came over personally to receive it, and I need hardly

tell you that directly he arrived he entered into our hearts and

affections and has remained there ever since.

(Applause).”

Webb

responded, “I have come over here personally to say

‘Thank you’ in the sincerest and the directest and the

simplest way I can. And to assure you that all architects on the

other side of the water will deeply appreciate the fact that on

this, the jubilee day of your Institute, and the institution of

this gold medal, you should send it over to the other side ... It

has always been one of my happiest recollections that it fell to my

lot to have the privilege to hand our medal to Mr. McKim.

(Applause) He came over personally to receive it, and I need hardly

tell you that directly he arrived he entered into our hearts and

affections and has remained there ever since.

(Applause).”

Later, Webb would win the hearts of the Americans when, in

responding to a toast, he said “As we are all making

architectural similes tonight, I compare myself, and have done so

all the evening, to a little house in New York surrounded by

skyscrapers. I hope these gentlemen will not mind this comparison,

but, of course, in speaking of skyscrapers, I refer only to the

good ones.”

Roosevelt assists in a grand

exposition

There would be another convention in 1907, the 41st, held in

November, in which Day suggested, “It is in the service of the

people and not of its own members that the Institute finds, and

will find, its widest and best field. It is by unconsciously

stimulating in its members a desire and ability to be of public

service that it will find its greatest usefulness.” Noting

that there was opposition to location of the Grant Memorial at the

foot of the West Front of the Capitol on the Mall, the AIA

reiterated its firm support for that location, as suggested by the

Park Commission Plan, and proposed a memorial to artist and

sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens who, in 1907, had “died as one

of the acknowledged masters of his time.”

After approval

of the undertaking, AIA President Gilbert and Secretary Brown

undertook the planning of the memorial meeting. Mrs. Saint-Gaudens

participation was secured, space at the Corcoran Gallery was set

aside, and Brown and Gilbert began collecting Saint-Gaudens’

works for the exhibition.

After approval

of the undertaking, AIA President Gilbert and Secretary Brown

undertook the planning of the memorial meeting. Mrs. Saint-Gaudens

participation was secured, space at the Corcoran Gallery was set

aside, and Brown and Gilbert began collecting Saint-Gaudens’

works for the exhibition.

The pieces, from the Saint-Gaudens studio, loaned from museums,

institutions, and private collections, were carefully installed by

Brown and his coworkers, often working late into the night. One

piece that Brown felt was important for the exhibition was a bust

of General Sherman, which was at West Point, but West Point would

not part with it. Brown appealed to President Theodore Roosevelt,

who told his secretary to direct West Point to send the bust.

“A few days before the exhibition opened, Roosevelt and Mrs.

Roosevelt came into the gallery, inspecting the pieces of sculpture

that were in place. Seeing me [Brown] he said: ‘Have you

gotten the bust of General Sherman?’ I replied, ‘No, Mr.

President, I’ve not even heard that we could get it.’

Roosevelt walked toward the office. In a few minutes Mrs. Roosevelt

came back and said ‘The President wants to see you.’ I

followed her back to the office where we found the President. He

then dictated the following telegram: ‘Col. Scott, see to it

personally that the Bust of General Sherman is at the Corcoran

Gallery within twenty-four hours.’ ‘That will bring

it,’ said Theodore Roosevelt, bringing his fist down with a

bang upon the desk. It was delivered at the Corcoran Gallery within

twenty-four hours, brought by a special messenger.”

In the atrium at the Corcoran, Saint-Gaudens’ Victory-Peace,

“laurel crowned, right arm extended and holding in her left

hand an olive branch,” was placed on the landing of the great

marble stair. “She appeared to move forward gracefully,”

Brown wrote, “as she welcomed the guest[s].” A

speaker’s stand, in keeping with the style of the hall, was

erected in front of Victory-Peace. There, on December 15, 1908, at

9 p.m. before 156 of Saint-Gaudens’ works, the AIA paid its

tribute.

Roosevelt

spoke: “He worked among his own people, and his work was of

his own time; but yet it was of all time, for in his subjects he

ever seized and portrayed that which was undying.”

Roosevelt

spoke: “He worked among his own people, and his work was of

his own time; but yet it was of all time, for in his subjects he

ever seized and portrayed that which was undying.”

Roosevelt praised the coinage Saint-Gaudens had designed for the

United States: “I believe, more beautiful than any coins since

the days of the Greeks,” and of art in America. “In any

nation those citizens who possess the pride in their nationality,

without which they cannot claim to be good citizens, must feel a

particular satisfaction in the deeds of every man who adds to the

sum of worthy national achievement . . . Particularly should this

be so with us in America. As is natural we have won our successes

in the field of an abounding material achievements; we have

conquered a continent; we have laced it with railways, we have

dotted it with cities. Quite unconsciously, and as a mere incident

to this industrial growth, we have produced some really marvelous

artistic effects. Take for instance, the sight offered the man who

travels on the railroad from Pittsburgh through the line of iron

and steel towns which stretch along the Monongahela. I shall never

forget a journey I thus made a year or so ago. The morning was

misty, with showers of rain. The flames from the pipes and doors of

the blast furnaces flickered red through the haze. The huge

chimneys and machinery were of strange and monstrous shapes. From

the funnels the smoke came saffron, orange, green, and blue, like a

landscape of Turner. What a chance for an artist of real genius!

Again, some day people will realize that one effect of the

‘skyscrapers’ of New York, of the massing of buildings of

enormous size and height on an island surrounded by waterways, has

been to produce a city of singularly imposing type and of

unexampled picturesqueness. A great artist will yet arise to bring

before our eyes that powerful irregular skyline of the great city

at sunset, or in the noonday brightness, and, above all, at night,

when the lights flash from the dark mountainous mass of buildings,

from the stately bridges that span the East River, and from the

myriad craft that blaze as they ply to and fro across the

waters.”

And of

Saint-Gaudens and his statue of Lincoln: “We look . . .

stirred to awe and wonder and devotion for the great man who, in

strength and sorrow, bore the people’s burdens through the

four years of our direst need, and then, standing as a high priest

between the horns of the altar, poured out his lifeblood for the

nation whose life he had saved. In this quality of showing the

soul, Saint-Gaudens’ figures are more impressive than the most

beautiful figures that have come down from the art of ancient

Greece; for their unequaled beauty is of form merely, and

Saint-Gaudens’ is of the spirit within.” The guests, an

astounding number near 2,000, were, Brown noted “an imposing

sight as they passed by the receiving line.” The membership of

the Institute then was just 868. Clearly events such as the

Saint-Gaudens exhibition reached a press and public considerably

larger than the AIA membership.

And of

Saint-Gaudens and his statue of Lincoln: “We look . . .

stirred to awe and wonder and devotion for the great man who, in

strength and sorrow, bore the people’s burdens through the

four years of our direst need, and then, standing as a high priest

between the horns of the altar, poured out his lifeblood for the

nation whose life he had saved. In this quality of showing the

soul, Saint-Gaudens’ figures are more impressive than the most

beautiful figures that have come down from the art of ancient

Greece; for their unequaled beauty is of form merely, and

Saint-Gaudens’ is of the spirit within.” The guests, an

astounding number near 2,000, were, Brown noted “an imposing

sight as they passed by the receiving line.” The membership of

the Institute then was just 868. Clearly events such as the

Saint-Gaudens exhibition reached a press and public considerably

larger than the AIA membership.

The AIA shapes its adopted capital

city

AIA President Cass Gilbert noted in his address in 1908 that

President Roosevelt, “in calling together the notable

conference of the governors for consideration of the conservation

of the natural resources of our country, invited the American

Institute of Architects, as one of a few organizations of national

scope, to take part therein, and we have now an Institute Committee

acting with the Conservation Commission, which grew out of that

conference. This commission will, I believe, become one of the

greatest powers for national good that has ever been created.”

The convention voiced support for construction of the Lincoln

Memorial on the Mall site recommended by the Park Commission, and

the awarding of a Gold Medal to Charles McKim was authorized. The

Board reported that “The remains of Peter [sic] Charles

L’Enfant, which were interred on the Digg’s Farm in

Maryland, are to be removed to Arlington.” The removal and

reburial could be reported at the next convention, in 1909, but the

public celebration was not to come until 1911 with the unveiling of

a memorial designed by AIA member Welles Bosworth, in a ceremony

planned by Brown.

As Brown

and Gilbert talked with President Roosevelt, Roosevelt began to

talk about leaving a “legacy” to the AIA. The idea was

never fully defined, but a letter from the White House, signed by

Roosevelt and dated Dec. 19, 1908, arrived at the Octagon on

December 21. The President had evidently kept the letter before him

for a while, making changes in his own hand, before he was

satisfied and sent it. “My dear Mr. Gilbert: Now that I am

about to leave office there is something I should like to say thru

you to the American Institute of Architects. During my incumbency

of the Presidency the White House, under Mr. McKim’s

direction, was restored to the beauty, dignity and simplicity of

its original plan. It is now, without and within, literally the

ideal house for the head of a great democratic republic. It should

be a matter of pride and honorable obligation to the whole Nation

to prevent its being in any way marred. If I had it in my power as

I leave office, I should like to leave as a legacy to you, and to

the American Institute of Architects, the duty of preserving a

perpetual ‘eye of guardianship’ over the White House to

see that it is kept unchanged and unmarred from this time on.

Sincerely yours, [signed] Theodore Roosevelt.

As Brown

and Gilbert talked with President Roosevelt, Roosevelt began to

talk about leaving a “legacy” to the AIA. The idea was

never fully defined, but a letter from the White House, signed by

Roosevelt and dated Dec. 19, 1908, arrived at the Octagon on

December 21. The President had evidently kept the letter before him

for a while, making changes in his own hand, before he was

satisfied and sent it. “My dear Mr. Gilbert: Now that I am

about to leave office there is something I should like to say thru

you to the American Institute of Architects. During my incumbency

of the Presidency the White House, under Mr. McKim’s

direction, was restored to the beauty, dignity and simplicity of

its original plan. It is now, without and within, literally the

ideal house for the head of a great democratic republic. It should

be a matter of pride and honorable obligation to the whole Nation

to prevent its being in any way marred. If I had it in my power as

I leave office, I should like to leave as a legacy to you, and to

the American Institute of Architects, the duty of preserving a

perpetual ‘eye of guardianship’ over the White House to

see that it is kept unchanged and unmarred from this time on.

Sincerely yours, [signed] Theodore Roosevelt.

Gilbert responded “I have no hesitation in assuring you, Mr.

President, that the American Institute of Architects will accept

all the honorable obligation which your letter implies and will

lend its influence always to the preservation of the White House as

it now stands unchanged and unmarred for future generations of the

American people.”

Copyright 2005 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page