|

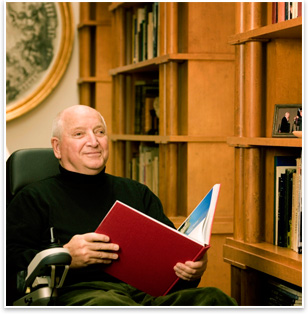

Michael Graves, FAIA, Awarded the 2010 Topaz

Medallion

by Zach Mortice

Associate Editor

Summary: Michael

Graves, FAIA, the trendsetting Postmodernist who has inspired generations

of architects and architectural educators through his long association

with the Princeton University

School of Architecture, is the 2010 AIA/ACSA Topaz Medallion for Excellence in Architectural

Education recipient. The Topaz Medallion honors an individual that

has been intensely involved in architecture education for a decade

or more. He will be awarded the medallion at the Association of Collegiate

Schools of Architecture (ACSA) annual meeting in New Orleans in March.

The AIA will also recognize Graves at the 2010 National Convention

in Miami in June.

Graves arrived

in Princeton, N.J. to begin teaching and practicing more than 40

years ago, during a critical juncture in the evolution of Modernism,

and he used both of these endeavors to re-establish the primacy

of history, culture, and context in architecture for multitudes of

students. His influence in instilling these sensibilities in the

contemporary architect is so wide and pervasive that it’s often

hard not to take for granted. To accomplish this in a purely academic

setting is notable enough, but Graves has also maintained an eminent

and widely-known design practice that has wholly integrated his teachings

in ways that have pushed Modernism in fresh, new directions. Graves arrived

in Princeton, N.J. to begin teaching and practicing more than 40

years ago, during a critical juncture in the evolution of Modernism,

and he used both of these endeavors to re-establish the primacy

of history, culture, and context in architecture for multitudes of

students. His influence in instilling these sensibilities in the

contemporary architect is so wide and pervasive that it’s often

hard not to take for granted. To accomplish this in a purely academic

setting is notable enough, but Graves has also maintained an eminent

and widely-known design practice that has wholly integrated his teachings

in ways that have pushed Modernism in fresh, new directions.

“For me,” Graves said in his Topaz submission portfolio, “the

profession of architecture is all about the joy of learning and creating,

the fulfillment comes with making a contribution to society. In my

career, I have been like a doctor in a teaching hospital in that

I practice, do research, and also teach, which for me is a way to

give back to the profession.”

Architecture that builds culture

Graves is a native of Indianapolis, and a graduate of the University

of Cincinnati as well as the Harvard Graduate School of Design,

but his most formative architectural experience was his study abroad

with the American Academy in Rome in 1960. In Europe, Graves was

inspired by the Italian Renaissance and Post-Renaissance buildings

and sculptures he saw. Among these relics of past golden ages,

he began to formulate ideas about the fundamental role buildings

play in shaping the history and culture of the people they serve;

ideas that would lead his practice and his entire academic career.

Graves began teaching at Princeton in 1962 and established his practice

there in 1964. By 1972, he was the youngest full professor at the

university. The mid-60s were a transitional period in the history

of Modernism, and Graves arrived on the scene at an ideal time to

further the evolution of architecture. It was at this time that

the unity of early Bauhaus Modernist pioneers began to splinter and

reform as architects struggled to find ways to add contextual, historical

elements to the blank-slate, ahistoric Modern design language. The

design movement that had begun with an attempt to reform society

by forsaking all previous historical design conventions and creating

a new, unified design language based on the form and logic of the

machine age had exhausted itself from formulating an approach to

architecture that proclaimed to have no historical antecedents. Graves

found a way to give new life to Modernism by explicitly appropriating

figurative historical and traditional design motifs in the pursuit

of wide, democratic appeal. It would eventually be labeled Postmodernism,

and Graves taught it as well as designed it.

When Graves began teaching, writes University of Virginia architecture

professor Robin Dripps in an AIA awards recommendation letter, architecture

schools didn’t teach the history of architecture as it practically

applied to the day’s contemporary architects. “Architecture

was thus removed from any meaningful engagement with the world. Contexts,

whether they were natural, constructed, political, or cultural, were

not part of the dialogue. Michael was to change all of this,” she

wrote. “Michael convinced his students that architecture was

the most important of our cultural endeavors and was responsible

for our understanding of the world and our actions within this world.

The outcome of his teaching,” which Dripps experienced firsthand

while at Princeton, “was a far more articulate discourse on

how architecture was understood, and most important, how it ought

to be made.”

The teacher’s teacher

For 39 years, from 1962 until 2001, Graves was a full-time tenured

professor, and he has only recently and moderately lessened his

academic responsibilities. In his time at Princeton, he taught

architecture design studios, supervised independent study programs,

been a thesis advisor, conducted lectures and seminars for students

and the public, served on juries, organized exhibitions, conducted

research, and been published in scholarly journals. He’s

brought in a diverse array of guest architecture professors to

teach, from Leon Krier to Peter Eisenman, FAIA, and has been a

visiting architecture professor at many other schools himself.

Graves has developed a reputation as an architect that is fully

integrated in the life of the academy, not a parachuting “starchitect” that

stops off at campus for a lecture in between meetings with clients.

“Michael’s commitment to remain in Princeton and locate

his professional activities there stands in sharp contrast to other

major architects who are often only transient visitors to education

programs,” wrote University of Cincinnati architecture professor

Jay Chatterjee, Assoc. AIA, in an AIA awards letter of recommendation.

Perhaps the most important measure of Graves’ influence and

success has been the number of his students that have gone on to

become architectural educators and deans themselves. “Every

time I tell someone that I went to Princeton, their reaction is to

ask me about by experience with Michael,” wrote Sarah Whiting,

an architecture professor at Princeton, in an AIA awards recommendation

letter.

For an architect that is largely associated with a single design

style within Modernism, Graves has a proud history of helping students

explore a wide range of aesthetic orientations. Alan Balfour, Assoc.

AIA, dean of the architecture program at Georgia Tech and recipient

of the 2000 Topaz Medallion, wrote in an AIA awards recommendation

letter that Graves “encouraged us to be as original as he,

but in our own way.”

“He has not taught me a method as much as a mindset: that

architecture matters, that architecture literally constructs culture,” wrote

Whiting in her AIA awards letter of recommendation.

Graves is also the honorary chair for the

American Institute of Architecture Students’ Freedom by Design community service

initiative. The goal of this initiative is to improve the life safety, dignity,

and comfort of low-income individuals with physical disabilities—an

intensely personal priority for Graves since 2003, when he became

paralyzed from the waist down as a result of an infection.

Portfolio and honors

Since establishing his architecture firm more than 40 years ago,

Graves has expanded his practice into a full range of design disciplines

contained within two separate firms. The

Michael Graves Design Group specializes in product

and graphic design, and has designed 1,800 consumer products (housewares,

furniture, utensils) to retailers like Target, Dansk, Disney, and

Alessi. Michael

Graves and Associates specializes in interior design,

planning, and architecture.

Graves began garnering serious attention in the architectural community

with his 1978 design for the unbuilt Fargo-Moorhead

Cultural Center Bridge, which joined North Dakota

and Minnesota with a bridge over the Red River that contains an art

museum and is bookended by an interpretive center for the region’s

cultural heritage on one side and a concert hall and public radio

and television station on the other. Other major projects Graves

has designed are the Humana Building in Louisville, the Portland

Municipal Services Building in Oregon, the Federal Reserve Bank of

Dallas—Houston

Branch, the Indianapolis Art Center, an addition to the Minneapolis

Institute of Arts, and the Engineering Research Center at the University

of Cincinnati.

Graves was the 2001 recipient of the AIA Gold Medal, and has won

12 national AIA Honor awards. Over 65 AIA New Jersey awards have

been collected by Graves’ firm. The New Jersey state component

also established the Michael Graves Lifetime Achievement Award in

his honor. |