2009

and Beyond | Revisiting the 2006 Report on Integrated Practice

| “Change or Perish”

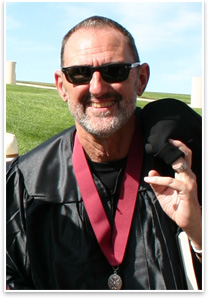

Thom Mayne, FAIA, at the AIA 2005 National Convention Fellows Investiture. Photo by Aaron Johnson, Innov8iv Design. by Robert Smith, AIA

Summary: When

Thom Mayne, FAIA, design director for Morphosis, told the AIA

members attending the AIA 2005 National Convention that they

must “change or perish,” he threw down a challenge

of rather substantial proportions. Then, by way of example, he

described the advanced design, documentation, and project delivery

techniques his firm had been applying in their work. While much

water has flowed under the bridge since that 2005 speech, Mayne

still feels the same way today about the challenges facing the

architecture profession. Hear the interview.

Recently AIArchitect asked Mayne to revisit the “Change or Perish” idea.

In the excerpts below from that interview, Mayne, along with Marty

Doscher (IT director at Morphosis) describe a professional environment

in which the notions of building information modeling and integrated

project delivery promote significant increases in empowerment and

possibilities among design professionals.

Q: Since 2005, what are the most interesting changes have you observed in the profession?

A: “Today I would think that you couldn't even run a practice without having advanced performance techniques for understanding the way your projects operate within functional terms, within environmental terms, within technological terms, and for looking at the development of a project in the early stages, the cost models that are connected to extremely precise performance objectives. It's not evolutionary … our clients expect this. And, given current economic conditions and the way the relationship with subcontractors and our engineers has evolved, a huge amount of these people already are advanced in these areas and also have expectations of receiving 3D drawings and not normative drawings.”

Q: How has your own practice changed during this interval?

A: “There's been continual growth. But I think the key here is that it's not been a singular thing. There’s been a shift in the whole culture of the office, and it's not tied to an isolated computational technique or particular BIM methodologies. It's been a complete shift in the nature of what we call an architectural practice and a shift in the whole culture—the culture of the practice.

And, despite this radical shift, it’s not spun out of control

. . . it's actually put us hugely in control. In a general

sense, what's taking place here is that we start with design ideas

that generally have to do with innovation, or solving unique problems

in the ways that have to do with their particular uniqueness. But

architecture is still site specific, it’s still program specific.

It remains so for huge amounts of our work.

This notion of integration is quite simply a radical shift into increasing empowerment and our ability to control the reality of our own profession. Now we're very much building things virtually and we're very much embedded “in” the construction. And, it's evolving into something that's taking place earlier and earlier in the process.

The historical phases of schematic design, DD, construction documents, etc.—that’s the tradition, right? However, if I were to give that talk again, I would say that the traditional pattern is also something that could be—should be—completely rethought. We must reconsider the notion of separating activities, which was very much connected to a traditional practice; i.e., the way we drew, the way we sketched, the very simple kind of notions about how we worked.

And, because we're essentially putting up virtual buildings, it's

more like the way they built in the Middle Ages . . . we design

and build in a simultaneous way. And today the practice is changing

to the point where the discussion in the office during schematic

design is more about ‘building things’ than ‘drawing

things’.”

Q: What about the design process itself . . . how

do you see it changing?

A: “I think we have to be harnessed immediately to a higher level design product and, by higher level, I mean a higher performance product. I came out of a meeting yesterday with our mechanical engineers—we're looking at a high performance skin that's moving, shading, removing heat energy from the building. And, in schematic design, my engineering group can tell me the delta of energy cost and put it in dollar terms. I'm dealing with a subcontractor who’s literally ready to mock it up and test it. We're just ending schematic design, and I can put a cost model to it. I'm preparing to talk to my client and say that we're going to put X amount of additional capital into the skin, which is a much higher performance skin that reduces the energy requirement of the building.”

Q: As you look to the future, how do you see the profession changing?

A: “We must innovate to revolutionize

ourselves. So, for example, in the near future, there will be massive

streams of data coming out of our buildings. For us, we must be able

to simulate our buildings—the life of our buildings—and

tap into these massive streams of data for the next generation. And,

we can't stop there, so we won't stop. There's a whole other dimension

to this, which is the kind of “evolutionary” part—not

the “revolutionary” part . . . and maybe that's what

this is about . . . how do you see it expanding into the rest

of the pyramid?

We must continually help the practice, the industry, evolve, but we can't lose sight of where we have to go, which is to totally transform. Right now, computational design is maybe marginalized, but it has to be the native way of working for every single architect in a few years, so we're continually pushing in these areas.

Now we model not to describe a building but to manage relationships between trades, which is a totally different reason than before. What we're finding is that the more facile we are with these tools, the more we use them for whatever challenges we're tackling—it frees us up to do other things. It frees us up to deal with more complexity during early design because we now have a way to handle it. We're constantly looking for new opportunities to employ these tools that we're comfortable with. But we're also tapping into whatever is coming next. In the very near future, robots will assemble buildings. What does that allow you to do? Just the fact that it's happening, what does that allow you to do? What opportunities does that open up? And so that's what we're looking for.”

And, with that challenge, Thom Mayne once again turns our attention back to his original challenge: Will we change or will we perish? |