House for a Greener Future

by Michael J. Crosbie, PhD, AIA

Summary: “The House of the Future” often tells you more about the people imagining how we will live in a distant time than what life will really be like down the road a piece. For example, in the mid-1950s, Disneyland, with the help of the Monsanto company, built its own House of the Future, nearly all of it made of plastic, with a microwave range, gigantic TV screens, electrically operated storage cabinets, vinyl plastic floors, molded-plastic bathrooms, fiberglass, and other petro-based materials. In the age of Eisenhower, this was pretty radical stuff, but it was also a vision of living in the future that was based on extending our reliance on cheap oil into infinity. In 1967, as things began to heat up in the Middle East, Disney tore down its house for a plastic future. This summer Disney opened a new House of the Future at Disneyland. It likewise tells us more about how we wish that the bad habits we’ve grown accustomed to (lots of energy consumption to power electronics and a plethora of entertainment outlets) will go unchecked, even as oil prices continue to fluctuate upward.

There’s another version of the House of the Future that is closer to the way we’re likely to be living. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Concept Home contains a number of design strategies that any architect interested in a more sustainable future should know about and consider applying in the field. HUD’s Concept Home is not radical in appearance, but it brings together a number of ideas that make it more resource efficient, energy conscious, and adaptable. The design is based on six principles. There’s another version of the House of the Future that is closer to the way we’re likely to be living. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Concept Home contains a number of design strategies that any architect interested in a more sustainable future should know about and consider applying in the field. HUD’s Concept Home is not radical in appearance, but it brings together a number of ideas that make it more resource efficient, energy conscious, and adaptable. The design is based on six principles.

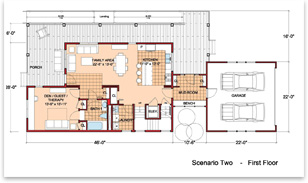

First, the Concept Home promotes flexible floor plans. This allows a family to alter spaces as living dynamics change—more kids, move-in in-laws, shrinking families, etc. Partition systems that can be changed by the inhabitants allow a family to age in place instead of having to move every time space needs change—a more resource-efficient way of adapting your house for the future. One example is the stair layout—a U-shaped arrangement with an open core space in the middle dedicated to storage space. At a later date an elevator can be installed in the core space.

The second design principle also aids flexibility—disentangling utilities and keeping them out of partitioning systems, or locating them in a way that makes it easier to access them, upgrade them, and move them as the floor plan changes. Wireless technologies will make an impact here.

Improved production process is the third design principle, which puts an emphasis on factory-built components. I’ve discussed this sustainable approach in previous columns. There are lots of green advantages in terms of material conservation and construction quality that come from streamlining the production process of the American home. The Concept Home promotes consolidated factory-installed mechanical systems and modular construction.

The fourth principle, alternative basic materials, highlights new green products, equipment, and all the other stuff from which we will construct our homes. The Concept Home suggests synthetic gypsum in place of conventional gyp-board walls, while switchable glazings are promoted for cutting solar gain on some of the windows. Passive shading is probably a better alternative, but architects should be exploring new green materials and products. The fourth principle, alternative basic materials, highlights new green products, equipment, and all the other stuff from which we will construct our homes. The Concept Home suggests synthetic gypsum in place of conventional gyp-board walls, while switchable glazings are promoted for cutting solar gain on some of the windows. Passive shading is probably a better alternative, but architects should be exploring new green materials and products.

Standardized measurements for materials and how they go together is the fifth principle, and one that has been hard to achieve. As the global marketplace for building products expands, the American market will have to go completely metric, which will make the interface problem easier to deal with.

The Concept House’s sixth design principle is integrated function, which is the goal of getting more out of what is already there. For example, whole-house ventilation should be integrated into the heating and cooling system from the start, instead of being added later. Another example is a dual-fuel HVAC system that integrates the furnace and heat pump. Photovoltaic roofing shingles and tiles are another integrated function alternative.

Is this sexy stuff? Not really. Does this mean that the Concept Home won’t fly with architects who want to design houses for a more sustainable future? It shouldn’t. HUD’s Concept Home principles are a starting point. Take them and be as sexy as you dare. |

There’s another version of the House of the Future that is closer to the way we’re likely to be living. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Concept Home contains a number of design strategies that any architect interested in a more sustainable future should know about and consider applying in the field. HUD’s Concept Home is not radical in appearance, but it brings together a number of ideas that make it more resource efficient, energy conscious, and adaptable. The design is based on

There’s another version of the House of the Future that is closer to the way we’re likely to be living. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Concept Home contains a number of design strategies that any architect interested in a more sustainable future should know about and consider applying in the field. HUD’s Concept Home is not radical in appearance, but it brings together a number of ideas that make it more resource efficient, energy conscious, and adaptable. The design is based on  The fourth principle, alternative basic materials, highlights new green products, equipment, and all the other stuff from which we will construct our homes. The Concept Home suggests synthetic gypsum in place of conventional gyp-board walls, while switchable glazings are promoted for cutting solar gain on some of the windows. Passive shading is probably a better alternative, but architects should be exploring new green materials and products.

The fourth principle, alternative basic materials, highlights new green products, equipment, and all the other stuff from which we will construct our homes. The Concept Home suggests synthetic gypsum in place of conventional gyp-board walls, while switchable glazings are promoted for cutting solar gain on some of the windows. Passive shading is probably a better alternative, but architects should be exploring new green materials and products.