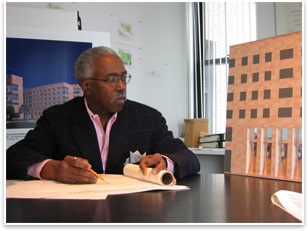

David Lee, FAIA David Lee, FAIA

Summary: David Lee, FAIA, is a principal with Stull and Lee, Inc., in Boston, where he directs a wide array of architectural, urban design, and planning projects. Lee currently is an adjunct professor at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design and has been on the faculties of the Rhode Island School of Design and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Lee served on the Design Arts Overview Panel of the National Endowment for the Arts, was an invited participant to the Presidential Round Table on Design in Little Rock, Ark., and was a design resource person for the First International Mayors’ Institute on City Design in Warsaw, Poland. He is a past president of the Boston Society of Architects and recipient of BSA’s Year 2000 Award of Honor. Education Career with Stull and Lee Brief description of practice Becoming an architect Secondly, there was a TV program on Friday nights. As a kid, Fridays and Saturdays were the only nights you could stay up late—and this show started at 9, which was the stratosphere for an eight-year-old kid. I would stay up and watch these movies. The sponsor was The Community Builders in Chicago, and the commercials would show before-and-after shots of houses they had renovated. They did things like raising the roof, adding dormers, enclosing a porch, or work on a basement, where they’d get rid of mold or replace coal-fired burners with more efficient gas or oil plants. They’d sometimes show models of how they would do all of that, and I was just fascinated by the before and afters. To this day, adaptive reuse is still an important component of our work. On the Stull and Lee Corridor tours at the AIA Convention Over 20 years ago, we first got involved with that from community protests for what had initially been planned to be an interstate highway right through those neighborhoods. The community turned that away and came up with alternatives for mass transit and local street improvements. We were working with a small grant from Model Cities (with a lot of student volunteers) as the design support for this community group and helped develop this alternative concept. Ultimately, then-Governor of Massachusetts Frank Sargent, who had an architecture background, halted continuation of the highway and opted instead for mass transit and redevelopment of the corridor. As a result of that, we played a role both in the environmental impact studies and the preliminary and final engineering of all of this work including the design of all the system-wide elements, platform furnishings, etc. We designed the Ruggles Street Station, one of the three largest stations in the system, and were instrumental in developing and designing buildings on some of the parcels that had originally been cleared for the highway and were redesignated, including the Roxbury Community College, the nearby Boston Police headquarters, a 1,000-car parking garage for Northeastern University, and an office building that now is also owned by Northeastern University. We did some housing further up the corridor at Mass Avenue as well as an award-winning ventilation shaft as part of the corridor that runs through the South End. We also conceived the notion of a linear park, which runs the 5.5-mile length of the corridor and complements the Olmstead Emerald Necklace. As a result of all of that investment in the 20 years since, a number of new housing developments have sprung up, and buildings that were boarded-up facing where the trains used to run in an open depression now are opening onto the landscape deck. The community works along with the metropolitan district commission in a volunteer effort to plant and maintain the gardens throughout the length of the corridor. It has become one of those really important public investments that leveraged private investment tremendously. Helping out in New Orleans

I came back to Boston and developed on a scrap of paper on the trolley an idea for the memorial. The problem was that we had a little less than a month to get design drawings, permits, additional funding, and someone to build it. As they say, the force was with us, and we were able to get Walton Construction, a large local contractor, to donate labor and materials. We got the permits pushed right through, and we got the whole thing built and in place for the one year anniversary of Katrina. In a ceremony that was covered by worldwide, national, and local press, the memorial was dedicated with the governor, the mayor, residents, and other dignitaries in attendance. It is the first thing you see as you come over the Claiborne Avenue Bridge into the Lower Ninth Ward, and it is treasured by the residents. They have asked me to design an informational plaque or something to explain the design concept, which I hope to get to soon. I grew up on the south side of Chicago and, like other African-American families, as segregation eased we moved further and further out from the core neighborhoods, but what we left behind was better than what we moved to in my opinion, certainly architecturally. I used to try to talk to people about the importance of these inner city assets, and my message was that one of these days gas is going to be as much as $2 a gallon, and people will come streaming back to the cities. I guess $4 was the price point, but now we’re seeing a real rethinking of higher density urban living and it’s also a more sustainable approach. As we are all becoming much more sensitive to the issue of sustainability, if we can couple that with the political will to reinvest in our cities—including our school systems and transportation systems—then I see a reemergence of the urban centers as new old frontiers for America in the design community. Currently reading What you wish you’d known about practice as a student And, frankly, I wish I were more of a self-promoter. Maybe I’m of a mixed bag about this, but I’ve seen some shameless self promotions by other architects of their work, as well as the work of others without attribution. I think as a profession we need to be more honest about that. But, if I had one thing, I would wish to have more business discipline—and every architect will say this—to be as selective about clients as clients are about selecting architects. As architects, we fall in love with what we’re doing and we do the work and hope to get paid in a timely fashion and to the value of the work itself. But sometimes we let our love of what we’re doing trump our good sense. Best practice tip |

||

Copyright 2008 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› Diversity: Three Contemporary Star Architects

Following one of the community meetings, I was approached by the councilwoman who represents the Lower Ninth Ward with a request from the neighborhood council to put together some sort of commemoration to honor the residents and victims of the storm. She said that Lowe’s and a group of lawyers were making a contribution to perhaps get some plantings and a few benches in place as a memorial. She asked my opinion about a potential site, how many benches and plantings might they need, etc. I asked her to let me think about it but I thought we might be able to do something more ambitious.

Following one of the community meetings, I was approached by the councilwoman who represents the Lower Ninth Ward with a request from the neighborhood council to put together some sort of commemoration to honor the residents and victims of the storm. She said that Lowe’s and a group of lawyers were making a contribution to perhaps get some plantings and a few benches in place as a memorial. She asked my opinion about a potential site, how many benches and plantings might they need, etc. I asked her to let me think about it but I thought we might be able to do something more ambitious.