|

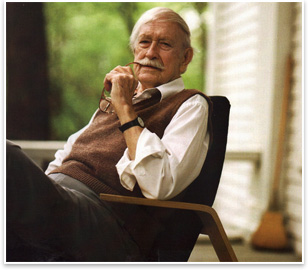

Ralph Rapson, FAIA Remembered

A Fellow of the Institute and the 1987 recipient of the AIA/ACSA Topaz Medallion, Rapson’s life is a litany of accomplishment. He headed the University of Minnesota School of Architecture for 30 years. “He was the dean of Minnesota’s architecture community and the last of the second generation of Modernists in America still practicing,” notes Thomas Fisher, Assoc. AIA, current dean of the school. “His passing ends an era in American architecture as well as in the history of the school, and he will be very much missed by the thousands of people he influenced.” “Ralph was a treasure to all who were fortunate enough to know him,” adds AIA Minnesota Executive Vice President Beverly Hauschild-Baron, Hon AIA. He will be greatly missed in our community and beyond. It hardly seems possible to think about the architecture profession in Minnesota without Ralph Rapson. It’s good that he lived to such a grand old age and shared his life’s work with so many.” The making of a Modernist In the early ’40s, Rapson moved to Chicago to teach under Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, the former Bauhaus professor who had set up the experimental New Bauhaus there. In the years at Cranbrook and in Chicago—at the end of the Great Depression and during the war—private construction was at a near standstill, and Rapson kept himself and his ideas going by participating in and winning competitions. In 1939, he, Eero Saarinen, and Fred James won a competition designing a festival theater and fine arts center for the College of William and Mary, which would become the first Modern building on an American campus. In 1945, with his Greenbelt House, he was the youngest of nine architects selected for the Arts and Architecture Case Study competition.

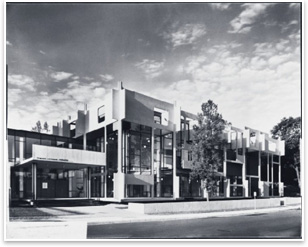

In 1954, he accepted the position as chair of the University of Minnesota School of Architecture (now the College of Design, School of Architecture). In his 30 year tenure in that position, he led that program to national prominence. His best-known work is the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis, completed in 1963. To eliminate the separation of audience and performers, he wrapped the seating around the thrust stage so no one of the 200 in the audience was more than 45 feet from the performance, and everyone could participate in, as he said, “the delight, fantasy, and stimulation of the theater experience itself.” To his dismay, Rapson saw the Walker Art Center raze the Guthrie when it moved to the New Guthrie in Minneapolis (designed by recent Pritzker recipient Jean Nouvel). “It’s disappointing to me that an arts institution would be so disrespectful,” Rapson said of the situation in 2002. Revered by students and colleagues “He was a wonderful, gracious person, humble and unassuming, and to see the love the students had for him was incredible,” Vosbeck continues. “His influence, through his students, has spread all over the world. And his influence reached beyond architecture. The whole arts community stood behind him on saving the Guthrie.” “One of the most impressive was that he played the cards he was dealt, and admirably,” says 1995 Chancellor of the College of Fellows Robert Coles, FAIA, referring to the fact that Rapson, renowned for his drawing skills even though his deformed right arm was amputated when he was a child. He first got to know Rapson when Coles was a Rotch Traveling Fellow in 1955 while at MIT. One requirement was to submit regular reports, Coles recalls. “As an African American, I felt I should emulate his diligence. We shared the drive to overcome adversity,” Coles says. Active till his death, Rapson spent his last evening on his exercise bike and drawing, according to Kresge Foundation President Rip Rapson, the architect’s eldest son.

|

||

Copyright 2008 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design