The Design Oasis of Cincinnati The Design Oasis of CincinnatiPublicly and privately, a remote Midwestern metropolis has put itself at the forefront of contemporary architecture Summary: Cincinnati’s recent willingness to invest in international progressive architecture is more of a continued tradition than a break from the past when considered in the context of the city’s 20th-century design history. Like other similar cites, Cincinnati has become an ideal incubator for high-profile architects.

In 1989, University of Cincinnati administrators realized that they had a disparate and bland college campus, decentralized and awash in parking garages, lacking any cohesive identity. Steve Kenat, AIA, of the Cincinnati firm GBBN, worked on Libeskind’s Ascent and is a University of Cincinnati alum. “[I] signed on for an architectural studies program despite the campus,” he says. The campus had grown haphazardly, and needed a way to rebrand itself as a vibrant hub of learning, so the school hired landscape architect George Hargreaves to design a master plan that would build the university’s new identity out of the work of architecture’s professional vanguard. Today, students live in dormitories designed by Thom Mayne, FAIA, study in science classrooms by Frank Gehry, FAIA, and eat in cafeterias created by Charles Gwathmey, FAIA. Aspiring architects hone their skills in a complex by Peter Eisenman, FAIA. The campus has nine such “signature architect” buildings.

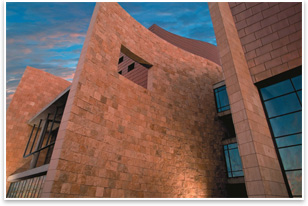

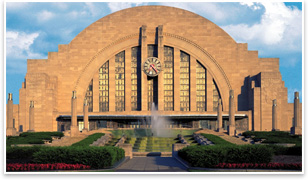

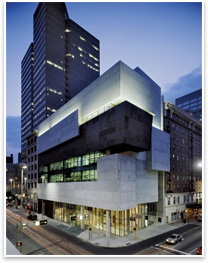

Cincinnati’s architectural landscape is still largely defined by Cass Gilbert’s elegantly columned Neo-Classical PNC Tower and the famously Art Deco Union Terminal train station by Paul Cret, with Alfred Fellheimer and Stewart Wagner. Outside of the university, victories have been sparing but bold: Hadid’s museum, Libeskind’s condo tower, and the news that Dutch firm Neutelings Riedjik’s first project in the U.S. will be an expansion to the Cincinnati Art Museum. For Cincinnati to have icons from the past that are still so warmly regarded (like Gilbert’s building and Union Terminal) the city must have had a tradition of making what were bold, contemporary choices. Kenat cites a group of four buildings by Daniel Burnham in Cincinnati, built from 1901 to 1903, and Frederick Law Olmstead’s plan for Spring Grove Cemetery in town. “We’ve always gone outside our immediate geography to find something special,” he says.

Kull says Cincinnati and other Midwestern cities where star international architects have made their initial splash are benefiting from the provincial run-up these architects want to make before their work lands in a coastal design capital like New York. Along with Libeskind’s first domestic foray in Denver, and Hadid’s Cincinnati debut, the first completed American project for Frenchman and Pritzker Prize-winner Jean Nouvel, Hon. FAIA, was in Minneapolis. Vienna-based Coop Himmelblau did their first American project at the Akron Museum of Art, and SANAA, a Japanese firm of rising eminence, brought an addition to the Toledo Museum of Art for their stateside debut. Today, all these architects (except Hadid) have a project in New York. “You might say it’s kind of like Broadway,” Kull says. “You develop a fantastic play—where do you try it out?—in Boston, or in Kansas City, or somewhere you can get your feet under you and then you move into New York.”

Kenat and Kull say that this local/non-local distinction is becoming less and less relevant in the rapidly converging global marketplace. (Their firm recently opened an office in Bejing.) And several architects said that working with these out-of-town firms exposed them to opportunities they couldn’t have gotten in their native city. And, besides, Cincinnatians know that a Cincinnati building by a Cincinnati firm is seldom big news. “Sometimes you get locals here, like everywhere else, who are more willing to accept something new when it comes from a briefcase from farther away,” Painter says. |

||

Copyright 2008 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› Consumer-Focused Hospital Planned for Cincinnati Suburb

› Three Schools Receive Practice Academy Pilot Program Grants

› Back to School

Visit AIA Cincinnati’s Web site.

See what the Regional and Urban Design Knowledge Community is up to.