| Sheila Kennedy, AIA

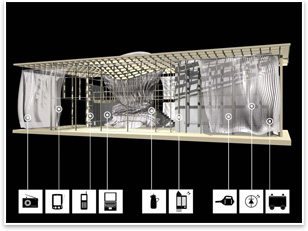

Founding KVA: It was just the two of us when we started in 1990. I met Frano in graduate school. We had done some competitions together and won. We enjoyed working with each other, so we knew that we wanted to open up our own practice as soon as we possibly could. Now there are 14 in the firm. On launching a materials research division: We have an interdisciplinary practice, so we take on projects that engage new materials, and sometimes traditional materials, in architecture. There was a lot of interest in the world in materials science around 1996-1997 with the discovery of the blue phosphor in Japan. The blue phosphor is a natural crystal that emits lights in the blue range; it was the missing element necessary to produce digital white light. We could see that there could be enormous consequences with semiconductors and materials and white digital light in architecture. Two years later, we launched MATx to explore those possibilities. The Portable Light: The Portable Light project emerged from our work with semiconductors between 1998 and 2000, when we launched MATx, and 2004 when we started the Portable Light project. We developed an area within architecture where we performed what’s called the vertical integration. We brought performative materials that either produced energy like photovoltaics do or produced digital light. We studied those materials and researched their effects and their possibilities and then developed ways to integrate those materials into building materials, such as concrete, glass, plywood, and textiles. The Portable Light project was an outgrowth of those experiments that we had been doing with LEDs and with photovoltaics. Semiconductor materials operate like little gates. They move from one state to another, so—with a little bit of natural sunlight for example—a semiconductor material can produce electricity. We call that material “photovoltaic” or “solar” material. The other side of that same coin is that when you introduce just a very little bit of electrical energy, materials will emit light—they throw off photons. That’s essentially what a light emitting diode is. What’s incredible about LEDs is that they’re extremely energy efficient. I’m very happy that our practice has been able to contribute to accelerating the adoption of digital light, or solid-state lighting, in architecture. The Portable Light project is now expanding. We were working with two sites in Mexico and one in Australia. We’re adding to that quite a large new project in KwaZulu-Natal, which is in South Africa, and another project in Nicaragua, both of which are with nonprofits. The project in Nicaragua is about education and training; enabling local communities to learn about conservation and take on conservation tasks. There, we are working with Paso Pacifico to figure out ways that local people and communities can be involved in protecting the land corridors linking North and South America that are extremely important from a bio-diversity point of view. The Portable Light project will be used in various different villages to support local education and school projects, and also to help with turtle conservation at night. We’re adapting the white light to red light with a snap-on lens, because the turtles aren’t bothered by red light. In South Africa, we are exploring the possibility of working collaboratively with the I-Teach program, which is a very innovative program that’s addressing the twin epidemics of HIV and tuberculosis in KwaZulu-Natal. Many patients who are suffering from HIV also have tuberculosis. There’s some very innovative programming going on that uses cell phones to give patients messages to remind them to take their medications. Many people have cell phones or could borrow a cell phone, but the electricity system is not reliable. Many people don’t even have electricity, so the Portable Light project will be integrated into a kit that will help people who are suffering from TB and HIV/AIDS to have electrical energy to power cell phones and have light. The SOFT HOUSE: The SOFT HOUSE takes its name from the soft path, the concept of many different sources of energy in a distributed system working together. It’s an idea authored by Amory Lovins of the Rocky Mountain Institute and it dates back to the 1970s. We asked ourselves how we could design a prefabricated house that could be affordable and that could have a point-of-purchase alternative energy system that a homeowner could tailor to her or his own energy needs and budget. We are working with a number of different manufacturers to make that idea happen. We have a prototype model that was at the Vitra Design Museum that demonstrated at full scale how something as simple as household curtains could be used to capture energy from the sun and store it in lightweight batteries. That energy could then be used to support a number of different household tasks while still having the house connected to a primary electrical grid. A homeowner would be paying less money for electrical services because the SOFT HOUSE allows a homeowner to take a number of different energy consumption applications off grid, particularly those that have to do with portable work media: laptop computers, digital cameras, PDAs. These pieces of equipment that everyone uses do consume energy and they’re very well suited for the DC ring, a direct current ring, which is the new hybrid distribution system that’s proposed in the SOFT HOUSE. The next architectural evolution: I think that, a lot of time, innovation in architecture or technology overstresses the novel, placing too much emphasis on the new. I believe it was Edwin Land who said: “It’s not that we need new ideas, but we need to stop having old ideas.” I think that there isn’t going to be a revolution in architecture, but I certainly hope there can be an evolution. Part of that evolution has to do with how practitioners and educators in architecture have become increasingly aware that the organizational concepts and spatial concepts that we inherited from Modernism are no longer adequate to meet the environmental and societal challenges of a world that is rapidly urbanizing. What I’m interested in is how the discipline of architecture as a whole and its allied fields of design can accelerate what I feel is a gradual cultural evolution from a commodity-based notion of energy, like oil or fossil fuels, to what I sometimes call a diaspora: that idea of disbursed collection of performative materials. Each of those materials would have its own formal and aesthetic problems and potentials, and each of those materials needs to be designed, fabricated, and integrated into multiple materials, surfaces, objects, and elements of architecture. It’s quite different than the inherited Modern idea that our building services should be encapsulated together within the space of a hollow wall. We’ve evolved beyond that and I think that understanding the consequences of this diaspora will be part of the next evolution. What’s important is that we begin thinking about that now. A person might ask: “Why should the discipline of architecture become involved in addressing these questions?” In emerging distributed models of energy, elements of urbanism, architecture, infrastructure, and mobile objects can overlap each other, at times engaging a traditional, centralized grid and at other times functioning independently. In projects such as the SOFT HOUSE or the Portable Light project, we’ve developed ways in which “independent” materials and architectural elements can also link with one another to become greater than the sum of their parts. Architecture is a medium well suited to explore these possibilities, which are fundamentally spatial and formal, social, and material. Hobbies: I love everything that has to do with the ocean and I enjoy swimming and snorkeling. I don’t know if this is a hobby, but the most forward edge of our research has been focusing on bioluminescent materials, or the way that nature produces light. I’ve been on some absolutely fascinating expeditions recently in Equador and in Baja looking at the phenomenon of bioluminescence. I’ve been looking at it in ocean-going bioluminescence, primarily in fish and also some jellyfish as well. Favorite retreat: I like to come into our studio early on Sunday morning. That’s my retreat. Last book read: I actually just read Italo Calvino’s Six Memos for the Next Millennium. There are two very good ones on lightness and on quickness. They’re all excellent, but the idea of agility in a practice of architecture is something that I’m very interested in. I try to re-read important books every so often and so I’ve just finished re-reading that book. Advice for young architects: Never underestimate the power of the architectural imagination. I would say that for young architects, the education that we get as architects provides us with a way of thinking that’s going to be increasingly important in the creative economy. If young architects could find a way to do their research and do work that interests them—and if they can find a way to intersect those interests and motivations with larger issues in the world—so much the better. |

||

Copyright 2008 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

SOFT HOUSE rendering courtesy of KVA MATx.

For more information on MATx or its projects, visit the Kennedy and Violich Architecture Web site.