Lattice Cube-Shaped Laboratory Offers a Dutch Treat

New Atlas Building opens at Wageningen University in the Netherlands

by Russell Boniface

Associate Editor

How do you . . . design an efficiently compact laboratory and office structure that is visually striking as well? How do you . . . design an efficiently compact laboratory and office structure that is visually striking as well?

Summary: Wageningen University in the Netherlands recently opened its Research Centre campus, anchored by the seven-floor Atlas Building that houses laboratories and offices. The Atlas Building is defined by its cube shape and concrete lattice design. New York-based Rafael Viñoly Architects designed the signature façade, which also supports a column-free interior with sloped ramps above its open atrium. Wageningen University and Research Centre is a leading education and research center focused on plant, animal, food, and environmental sciences. The Atlas Building is the recipient of a 2007 AIA New York State Award of Merit.

The 100,000-square-foot, seven-story Atlas Building anchors Wageningen University’s new Research Centre campus, known as the Centrum de Born. Responding to urban planning requirements that mandated a compact site and a “sculptural quality” to the building, Rafael Viñoly Architects designed the Atlas Building as a neat, cube-shaped structure with a concrete lattice façade. The Atlas Building serves the school’s Department of Environmental Sciences; one-third of its space is research labs and the remainder is office space. The 100,000-square-foot, seven-story Atlas Building anchors Wageningen University’s new Research Centre campus, known as the Centrum de Born. Responding to urban planning requirements that mandated a compact site and a “sculptural quality” to the building, Rafael Viñoly Architects designed the Atlas Building as a neat, cube-shaped structure with a concrete lattice façade. The Atlas Building serves the school’s Department of Environmental Sciences; one-third of its space is research labs and the remainder is office space.

The need to be compact and visually striking leads to negotiation

Mariana Kolova, project manager, Rafael Viñoly Architects, says the local Holland municipality mandated many requirements for the master plan of the Atlas Building. “The building needed to be on a compact footprint and have a strong structural, sculptural quality without projections, rooftop machinery, additional pavilions, or backsides,” she explains. “It had to be the first building one would see from the new entrance to the campus, and there could only be one road leading to it. They wanted it 10 stories high with a central area.”

This led to negotiation between Rafael Viñoly Architects and the municipality. Kolova wanted to honor the work of the scientists and students by providing a functional, interactive space for labs and offices with a central atrium. “It was strict but negotiable. We found some of their requirements didn’t work, like having 30 percent labs in a 10-story building,” Kolova says. “Our idea was it should be two or three stories. We made some diagrams showing how students come to these labs using a limited number of elevators and what that means for internal circulation. Finally, as often it happens in Holland, it was a compromise at seven floors.” This led to negotiation between Rafael Viñoly Architects and the municipality. Kolova wanted to honor the work of the scientists and students by providing a functional, interactive space for labs and offices with a central atrium. “It was strict but negotiable. We found some of their requirements didn’t work, like having 30 percent labs in a 10-story building,” Kolova says. “Our idea was it should be two or three stories. We made some diagrams showing how students come to these labs using a limited number of elevators and what that means for internal circulation. Finally, as often it happens in Holland, it was a compromise at seven floors.”

Lattice design combines form and function

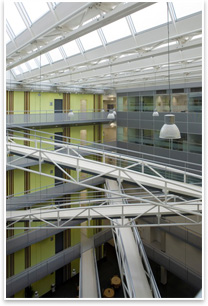

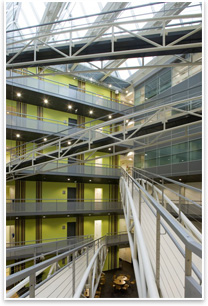

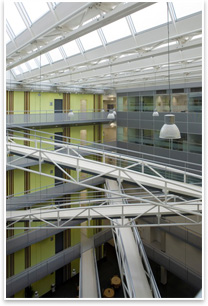

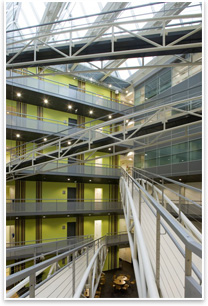

The concrete lattice façade met the design requirements of sculpture and flexibility while remaining within a budget. “The external concrete exoskeleton supports the building so there are no columns inside, not even along the perimeter,” Kolova points out. “We were trying to allow for as much flexibility as possible.”

Four sloped bridges above an open atrium connect the lab and office perimeter. Kolova and her team had to get a special permit for the bridges, because their slope didn’t meet Dutch building code. “We found that everything at the university is dynamic because environmental science is a young field. We wanted to encourage informal communication among scientists of the different disciplines by having an attractive middle space where they can meet while drinking coffee, relaxing, or checking e-mail at the lobby computer stations. Maybe they will informally exchange interesting project ideas,” Kolova says. Four sloped bridges above an open atrium connect the lab and office perimeter. Kolova and her team had to get a special permit for the bridges, because their slope didn’t meet Dutch building code. “We found that everything at the university is dynamic because environmental science is a young field. We wanted to encourage informal communication among scientists of the different disciplines by having an attractive middle space where they can meet while drinking coffee, relaxing, or checking e-mail at the lobby computer stations. Maybe they will informally exchange interesting project ideas,” Kolova says.

The Atlas Building houses 35 labs plus their mechanicals. “We designed uniform floor height for labs and offices, with floor plates as free of structure as possible. The mechanical spaces of the labs are immediately above or under spaces with the same floor height,” Kolova explains. “So, if they want to rebuild the lab into a two-level office, they remove the lab and mechanicals above or under it. Rebuilding labs and offices is a constant process in Holland, and what has happened in the past is that labs are being squeezed into office floors with ridiculous ceiling heights, which is quite unworkable.”

A skylighted roof featuring two slopes of 60 degrees caps the structure, echoing the style of an old industrial building roof. Because there are no columns, daylight flows down to the ground floor. “They know the exact position of the sun at any given moment. The users didn’t want shading of the skylight, because the whole point is seeing the sky. And everybody can open their window and overrule the shading by opening and closing their sunscreens. Everything is individually operable to make them feel good,” Kolova concludes. A skylighted roof featuring two slopes of 60 degrees caps the structure, echoing the style of an old industrial building roof. Because there are no columns, daylight flows down to the ground floor. “They know the exact position of the sun at any given moment. The users didn’t want shading of the skylight, because the whole point is seeing the sky. And everybody can open their window and overrule the shading by opening and closing their sunscreens. Everything is individually operable to make them feel good,” Kolova concludes.

|