|

Jane Jacobs and the Crucible of Prosperity

Over the deceased activist’s objections, the new Brooklyn waterfront will have to survive its success.

Though only separated by a few narrow blocks, the commercial and industrial districts of the northern Brooklyn neighborhood of Greenpoint are a world apart. On Manhattan Ave., the street bustles with small grocers, cafes, and local banks. Its rambling, 19th-century charm is rich in architectural diversity. Brownstones sit next to apartment blocks that sit next to neo-Gothic churches. The neighborhood has welcomed wave after wave of immigrants, and today it’s the heart of Brooklyn’s Polish community. Architecture historian, writer, and Brooklyn resident Francis Morrone would call it a “working class utopia” if this designation didn’t sound like such a knee-jerk liberal construction. Next to this bustling streetscape sits a disused vestige of the past known as the Brooklyn waterfront. Low-slung warehouses sit empty, and factories are hollow. Brick walls decay, and corrugated steel panels rust. On a rainy afternoon in October, workmen at the few remaining industrial and storage tenants walk out of these husks with boarded up windows and lock up chain link fences as soon as a curious walking tour group strolls through the desolate streets. Abandoned lots that are the result of a mysterious fire last year sprout weeds and refuse piles. A stone’s throw away from the Manhattan skyline, a decaying insularity pervades and the waterfront sits fallow. But developers have a remedy. In May of 2005, the New York City Council approved a plan put forth by developers to rezone almost 200 blocks of the Greenpoint and Williamsburg waterfront so that they can build a series of luxury high-rise apartment buildings connected by park spaces and waterfront esplanades. The developers believe that this “working class utopia” can co-exist with professional class elegance, but some residents and community activists are skeptical. They see the rezoning as a way to crush the remaining industrial economy and displace working class residents. The community assembled their own redevelopment plan (called 197a) that drew on the neighborhoods’ strengths to respect its current scale and retain its village-like atmosphere. But, according to the Gotham Gazette, the city has done nothing to implement this plan. Meanwhile, skyscrapers are already rising in Williamsburg.

Too rich or too poor Brooklyn, however, could hardly be called an area in decline. It’s in the midst of a demographic and cultural renaissance, as young professionals, artists, and new immigrants have been priced out of Manhattan and are making Brooklyn their home. Gentrification is already well established there, forcing these young creative types further east in an L-train migration that has moved the hipness frontier from Park Slope, to Williamsburg, to Bushwick. If these professional Manhattan émigrés are already being pushed further and further away from the city, what hope will working class, multi-ethnic communities have of staying in their neighborhoods once the waterfront is filled with sparkling luxury condos? “Ballet of the sidewalk” Jacobs was aware of how rapid success or (“oversucess”) could drain a city of diversity of uses. In Death and Life, she details how a prevailingly popular and successful single use can overwhelm and choke a neighborhood, spreading blandness and homogeneity. Any time a single use is deemed the most successful and lucrative in a given district and begins to crowd out other uses, Jacobs argues, the balance of the district is disturbed and vitality and new ideas are not likely to take root there. A block composed entirely of nightclubs is likely to be shuttered and deserted during the day and congested and stifling at night. “The triumph is hollow,” she wrote. “A most intricate and successful organism of economic mutual support and social mutual support has been destroyed by the process.” Why can’t a city just be a city? The rezoning plan seeks to protect the low-rise, mixed-use nature of the inland blocks, but some residents and planning experts are skeptical that the remaining industrial and commercial uses will remain. In the Gotham Gazette, City University of New York Professor Tom Angotti argues that further gentrification, spurred on by the construction of the luxury towers, will increase property values so that residential housing is far more lucrative than industry. The rezoning plan allows individual landowners in mixed-use zones to decide whether housing or industry will predominate, and there is no reason to suggest that Williamsburg and Greenpoint landlords won’t behave like rational consumers and adopt the use the market values most.

What, exactly, is a developer allowed to buy? Throughout the discussion, they reaffirmed that changes in settlement and density will always happen in dynamic urban environments. Carlton Brown, a founding partner of Full Spectrum, a development company that specializes in green and sustainable projects in emerging markets, says that people often fail to think about urban changes in long enough terms. One hundred fifty years ago, Brooklyn was inspiring pastoral odes by Walt Whitman. “In the span of cities [that’s] not really a long time” Brown says. “And so, Williamsburg was rezoned, and I can assure you that 130 years from now Williamsburg will look nothing like it looks like today.” For Brown, the task for the next 130 years is to manage this change so that it works for “a wide array of people so that we tie into this notion that there is ultimately enough to go around.” Beyond left and right “She was somebody was revered by both liberals and conservatives,” says Morrone. “If you read interviews with her, she sort of slightly changes her message to appeal to these people, and I think she did this very knowingly. She was very crafty in the way that she spoke to different groups.” The Municipal Art Society is hosting an exhibit through January 5, 2008, that features Jacobs‘ work, legacy, and democratic vision of what cities can be. The lasting impression that emerges from this showcase is the idea that cities, the great generators of culture in modern society, truly draw their vitality and richness not from their stock of museums, symphonies, art societies, or institutional heft, but from the plainspoken, everyday people who make up these organizations. For Jacobs, the city was a place where everyone’s fate is bound together. Isolation is impossible, because if one fails we all fail. This message of simple populist revisionism was always matched in the anecdotal and practical tone of her books, and in her letter to Mayor Bloomberg. “Come on,” she pleaded. “Do the right thing. The community really does know best.”

|

||

Copyright 2007 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

Recent related

› Municipal Art Society Honors Activist Jane Jacobs with a Multifaceted Program

For more information about “Jane Jacobs and the Future of New York.” program, visit the Municipal Art Society Web site.

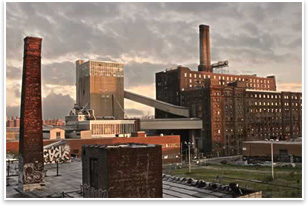

To try to protect the waterfront from wrecking ball-wielding developers and preserve this industrial past, the National Trust for Historic Buildings has declared the waterfront one of America’s 11 most endangered historic places this year. These photos are from the National Trust’s Web site, where more information can be obtained.

Photos

1. The Domino Sugar Refinery. Photo courtesy of the Municipal Art Society.

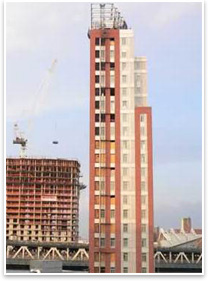

2. New towers under construction in the Down Under the Manhattan Bridge Overpass (DUMBO) area. Photo courtesy of DumboNYC.com

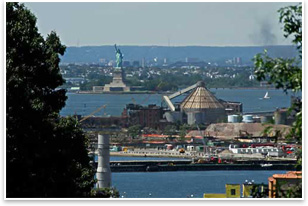

3. Red Hook and the Statue of Liberty. Photo courtesy of the Municipal Art Society of New York.

To combat what is one of the most ambitious rezoning projects in the city’s history, these neighborhood advocates experienced a bit of history themselves when Jane Jacobs, author of the

To combat what is one of the most ambitious rezoning projects in the city’s history, these neighborhood advocates experienced a bit of history themselves when Jane Jacobs, author of the