Jack

Travis, FAIA, on Black Identity Jack

Travis, FAIA, on Black Identity

Summary: Bronx-based architect Jack Travis, FAIA, sees young architects today much more interested in exploring issues of race, culture, and design than in the new so-called "Hip-Hop Architecture" expression, which he sees as an offshoot of a larger search for a "black" architectural expression. The trouble is, he says "our children in general lack a strong identifying nature with the historical references of Africa, and their professors are ill-equipped to support their inquiries." Travis spoke with AIArchitect contributing editor Stephen A. Kliment, FAIA, author of the current online Diversity series.

These subgroups all have different manifestations, and we are today all mixed with other races and cultures. But, over the centuries, we retain one single identifying characteristic, our “blackness.”

You observe "the ways of being" of the various groups and note the similarities and nuances in the use of space and their reaction to form in traditional post-colonial settings. Given this range of influences, how do you find inspiration? Travis. With people who are not so focused on Western traditions, such as those found in villages and small town enclaves in places like Senegal, Ghana, South Africa, and the Caribbean islands, you find extended family life styles and a spatial reference uninterrupted since the ancient tradition and sometimes markedly different from our way of thinking. For instance, the use of color, texture, and pattern is generous and often extremely intense in the dress, home furnishings, and marketplace. The pitch of sound in the public space is higher, and one feels the sense of place both spiritually and physically. I was taught in school that this way of embellishment is garish and even tacky. But as I find it in those places, it is exquisite and uplifting.

Travis. I like both, because, as an environmental designer, I am concerned with the dynamics of how people use space, in this case public space. There are similarities, but I am at once made aware of the differences. In Africa, in the marketplace, proximity and personal space boundaries are more intimate. Noise and verbal interchange are more intense. How one carries away merchandise differs markedly. In the marketplace, a young man or woman selling two fish caught that day in their little homemade dinghy can exist and sell their catch alongside fishermen who have hundreds to sell. I contend there are cultural differences in other typologies, such as residential, commercial, and spiritual worship that we have yet to recognize and respond to through design. We know of a Japanese Style, for instance, in all of the above typologies. When we as Americans build in other countries, what is our reference point for architectural expression? Surely not Colonial Style. Mostly we design our way, regardless of prevailing cultural architectural context. In an African village, I find practiced a natural sense of low-tech and sustainability. So there are lessons of GREEN design in the study of BLACK design.

Travis. I’m also completing two new projects in Harlem, working in joint venture with majority firms as cultural design consultant. One is the Kalahari Condominiums, with Frederic Schwartz Architects, P.C., a 240-unit residential complex located on 116th Street to open in summer 2008 (see illustration). The other is the Harlem Hospital expansion, with HOK Architects, including a New Patient Pavilion, renovation of all floors in the existing tower, and an atrium connection for the two structures (see illustration). Both buildings will exude a strong black cultural impact visually and tactilely in the urban planning, architecture, and interiors of the common spaces. |

||

Copyright 2007 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

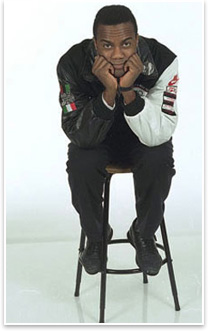

Jack Travis, FAIA, photo by Buck Ennis.

The north façade of the Kalahari condominium complex along 116th Street looking west, designed by Frederic Schwartz, FAIA, Schwartz Architects in joint venture with Studio JTA as cultural design consultant. GF55 Architects was the executive architect and architect of record, with David Gross, AIA, the partner in charge. Of the 250 market-rate units, developed by Full Spectrum and L&M Developers, 30 percent were reserved for moderate-income buyers and 20 percent for low-income buyers.

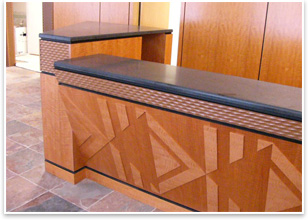

Kalahari interior lobby and main/security desk.

The Kalahari in its context, from the corner of Malcolm X Blvd. and 116th Street, looking east.

Exterior detail of an Adinkra symbol.

(Except where noted, photos by Jack Travis, FAIA, Studio JTA.)

Did you know . . . ?

A house in Brentwood, Calif., designed by the late

Paul Williams, African

American architect to many Hollywood stars, has been offered for sale for

$23,900,000, according to the new Sotheby’s catalog. It includes

three acres of “lush, verdant privacy …towering palms and

pine tress with rolling lawns, cascading waterfall and stream,”—along

with eight bedrooms and eight baths. Talk about ROI!

The new building for the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African

American History and Culture is expected to open in 2015 on the Washington,

D.C., Mall. The building is to cost between $300 and $500 million. The

Smithsonian recently awarded the architectural programming and exhibition

master planning contract to Freelon Bond—an association of architectural and design firms Davis Brody Bond of New York City and Washington, D.C., and The Freelon Group of Research Triangle Park, N.C.— and expects to solicit design

services in late 2008 or early 2009. Founding director Lonnie Bunch isn’t

waiting until 2005 to launch shows, which will be Web-based [http://nmaahc.si.edu/]

with links and tags.