| Architect Creates Design Synthesis Software

Onuma Planning System allows integration of vast amounts of information Summary: Following a lecture to students in Boston in the early 1980s, AIA Gold Medalist Michael Graves, FAIA, was asked to name the single most important attribute of a successful architect. Without a moment’s hesitation, he answered, “A high tolerance for ambiguity.” This insight sums up nicely why the design process is so hard to describe in words. At the start of every design project, a large number of factors—many conflicting, some unknown—must be considered and synthesized. And throughout the design process, new information must be integrated as efficiently as possible. Design synthesis—the ability to orchestrate the development of a coherent building design out of a morass of regulatory, programmatic, financial, aesthetic, environmental, social, and technical requirements—ranks high among the specialized, value-added skills that architects bring to the building and design construction process. Design synthesis is the unique domain of architects—no other member of the design and construction team brings it to the table—and its value increases exponentially with the complexity of the project. And yet, it is a skill for which architects are insufficiently recognized or compensated, in part because it is an implicit skill that architects apply routinely throughout the design process.

Onuma’s solution is a software tool—the Onuma Planning System™ (OPS)—that enables project teams to amass and synthesize programmatic information far more quickly than is possible with any current method. Asked to sum up OPS in a single sentence, Onuma says, “It allows you to test a lot of decisions early on and bump into problems early so that you can go in another direction.” His commitment to build OPS on open standards such as the IAI’s Industry Foundation Classes (IFCs), extensible markup language (XML), and other Internet and e-commerce standards means that the information generated in the planning process using OPS can be exchanged easily yet securely with all parties involved in a project and can be integrated easily into the design process by exporting in IFC format to building design applications such as ArchiCAD, Bentley Architecture, or Revit Architecture. Relying on open-source software solutions such as mySQL Enterprise Server, PHP Hypertext Preprocessor, and Apache HTTP Server means that data entered into OPS will never get locked up in a proprietary data format.

The user-friendly, Web-based graphical interfaces of OPS enable any team member—owner, architect, engineer, contractor, facility manager—to interact with project data in the way that is most familiar to each. “We can isolate parts of the system to users’ needs and perspectives,” says Onuma, “providing different entry points to the data for different users.” The Onuma Planning System is a building information modeling (BIM) tool that allows design teams to begin creating a building informational model using data in whatever format is most readily available or convenient: as structured data, such as an Excel spreadsheet; as simple, scaled, geometry; or both. Data exported from OPS is then available as an advanced starting point for the more complex building geometry of a building information model, which would otherwise have to be started from scratch. As the design develops, the more highly detailed BIM can later be brought back into OPS to test the design against the original program requirements.

OPS enables architects to perform rapid prototyping of multiple scenarios and early testing of conflicting requirements to determine whether they can be resolved, and if so, how. It allows many parties with a high degree of professional knowledge—architects, owners, engineers, security analysts, contractors, and others—to interact in real time and incorporate their specialized knowledge into the project data. It allows project teams to visualize all types of data, document the decisions they make, and continually eliminate ambiguities as decisions are made. Viewing the data, however, requires little or no professional knowledge or computer skill. An architect with only cursory knowledge of building security and bomb blast effects, for example, can open a data set and immediately see which spaces need attention through a graphical, color-coded interface. “The goal of the entire system,” says Onuma, “is to allow users having little knowledge and only minimal technical skill to get to the knowledge.” |

||

Copyright 2007 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

Kimon Onuma, AIA, is twice-recognized in the AIA Technology in Practice Knowledge Community

2007 Building Information Modeling Awards. This column will feature other BIM Award recipients in future editions.

Michael Tardif, Assoc. AIA, Hon. SDA is a freelance writer and editor in Bethesda, Md., and the former director of the AIA Center for Technology and Practice Management.

Image Captions and Credits

All images © 2007, Onuma, Inc.

Image 1

Spatial data from an Excel spreadsheet can be expressed in OPS as a bubble diagram, organized into a scaled floor plan, viewed as a 3D model, and integrated into a scaled site plan or massing model.

Image 2

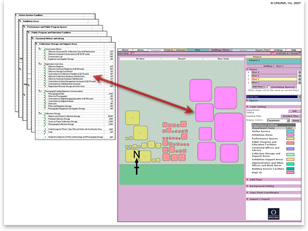

OPS allows data to be viewed in the way that is most convenient for the user. Here, data are shown as a written tabulation of spaces or as scaled, color-coded bubble diagrams.

Image 3

As OPS data become more richly developed, they can be exported as a massing model and placed on an actual site in Google Earth, allowing the design team to begin assessing site issues even before building design begins.