Top Shelf Amenities from the Bottom Up Top Shelf Amenities from the Bottom Up

Gerner Kronick + Valcarcel Architects make the Woolworth Building tower shine again, but still in Cass Gilbert’s image

by Zach Mortice

Assistant Editor

How do you . . . add modern luxury services to a historic commercial office building?

Summary: GKV’s renovation of the Woolworth Building tower is an attempt to lure small, boutique businesses to Lower Manhattan with unprecedented levels of service and comfort. The design adds new functions and features while still staying true to Cass Gilbert’s original design.

If Randy Gerner of GKV Architects’ design for the tower topping New York City’s Woolworth Building works on its own, it will have to be in the service of both 19th century aesthetics and 21st century amenities and convenience—two entirely different masters to be sure. If Randy Gerner of GKV Architects’ design for the tower topping New York City’s Woolworth Building works on its own, it will have to be in the service of both 19th century aesthetics and 21st century amenities and convenience—two entirely different masters to be sure.

The firm’s renovation of Cass Gilbert’s 167-foot-tall Gothic tower at 233 Broadway tears out stuffy and narrow elevator shafts and cramped corridors for a sweeping modernization—adding basic services like central air conditioning as well as premier executive amenities meant to attract high-priced tenants. It also hews as close as possible to Gilbert’s original design sensibility.

“Our intent is to be an extension of Cass Gilbert’s office,” Gerner says of his Woolworth Tower Club design, which is now under construction. To attempt to “renovate the building so that on the outside it’s the glorious, historic landmark that we all know, and on the inside it is a first-rate office building.”

Restoring a legend

The tower section of the building originally was conceived as the crown on Frank Woolworth’s dime store empire. When he decided he wanted to have the tallest building in the world, he rejected the original plans for a 24-story structure and had Gilbert tack on a tower that would stretch the building to 792 feet. This secured its place as the tallest in the world in 1913, until 1930, when a rapid succession of challengers (most notably the Empire State Building) surpassed it. Since then, the building has remained intact, but ill-suited for modern commercial office space. Installing Internet services was laborious, electrical service was strained, there was no central air conditioning, and all the elevators were tiny—so small that Gerner says, “an executive can’t even get a 96-inch sofa up to their floor.”

It was less than ideal for most all business tenants, and no one was making much money off the subsequent sub-par rental rates, so the consortium that owns the building allowed tenant leases to languish and put out a call for design proposals. With their strong expertise in interiors, GKV Architects won the competition and began to rethink this Lower Manhattan landmark. In some ways, Gerner and his team approached the tower just like Frank Woolworth did—as a distinctive presence with its own identity. So, they then looked for ways to tailor the project’s 100,000-square-feet to tenants that might be attracted to the building’s historical pedigree while still working in service to Gilberts design. It was less than ideal for most all business tenants, and no one was making much money off the subsequent sub-par rental rates, so the consortium that owns the building allowed tenant leases to languish and put out a call for design proposals. With their strong expertise in interiors, GKV Architects won the competition and began to rethink this Lower Manhattan landmark. In some ways, Gerner and his team approached the tower just like Frank Woolworth did—as a distinctive presence with its own identity. So, they then looked for ways to tailor the project’s 100,000-square-feet to tenants that might be attracted to the building’s historical pedigree while still working in service to Gilberts design.

And service is the key concept in GKV’s design. They formulated a plan that will attract lucrative boutique businesses (hedge funds, small law firms, etc.) to the small floor plates the building offers with an array of decadent services and amenities that recall the Woolworth Building’s post-Gilded Age past.

Putting the luxe in deluxe Putting the luxe in deluxe

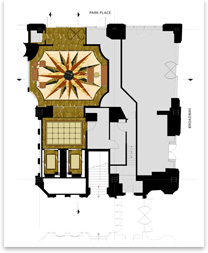

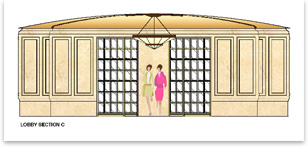

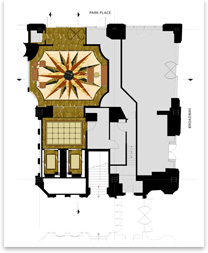

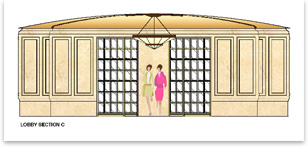

The basement of the Woolworth Building will house a health club where employees of tenant businesses will get to swim in what was Frank Woolworth’s personal pool. Doormen will greet visitors in the newly constructed lobby that faces Park Place and is replete with stone inlaid flooring in gold, rust, and beige and a tiled ceiling in blue turquoise, coral, and sand. The carpeted and wood-ceiling elevator lobbies lead employees into the new high-speed elevators, which Gerner says are more like lavishly decorated “small rooms” than the typical human cargo box.

GKV also vacated what was the world’s tallest internal chimney to install an elevator that only serves the Tower Club’s 29th through 51st floors. The office space’s floor plates are small (about 5,000 square feet or less) and get smaller as the building rises, and Gerner imagines the boutique businesses that become tenants will likely rent entire floors. The floors from the 52nd story and up are tiny, (some only 1,000 square feet) and will be conference rooms, social clubs, and dining areas. Gerner also envisions having a private chef onsite who will prepare meals for tenant employees while they work. At the 55th floor, a glass elevator takes guests to an observation deck. Gerner says he hopes all this will offer Lower Manhattan tenants a new level of service and convenience they’ve never seen before.

To chart this new frontier in office amenities, GKV didn’t look to typical commercial office space models. “We were thinking more of the services and amenities associated with a hotel, which will identify this as a unique property,” says Gerner. “Certainly, there is not going to be any other office space in Manhattan that will offer smaller tenants the amenities that this building will.” Gerner lists the Beaux-Arts Pierre Hotel on Fifth Avenue as an example of this type of amenity extravagance. To chart this new frontier in office amenities, GKV didn’t look to typical commercial office space models. “We were thinking more of the services and amenities associated with a hotel, which will identify this as a unique property,” says Gerner. “Certainly, there is not going to be any other office space in Manhattan that will offer smaller tenants the amenities that this building will.” Gerner lists the Beaux-Arts Pierre Hotel on Fifth Avenue as an example of this type of amenity extravagance.

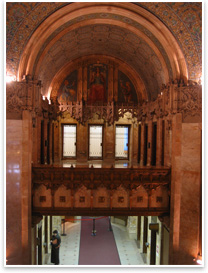

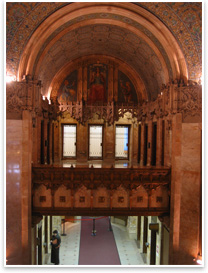

Pre-eminent building of its time

As it must be, GKV’s plans for the Tower Club are a preservation strategy. “Everything that we’re doing is completely consistent with the intent of the original architect,” says Gerner. “You won’t see anything that is inconsistent with the character of the building.” This includes a few references to the Gothic façade, like the vaulted glass mosaic ceiling in the new lobby, which uses the same stone as the original Cass Gilbert lobby. GKV’s design also restores Frank Woolworth’s 40th floor office from historical documents—a reminder that, as Gerner says, 233 Broadway was “the world’s pre-eminent office building of its time.”

|