|

Where History and Spirituality Meet, You’ll Find America Summary: The National Cathedral in Washington, D.C., is celebrating the 100-year anniversary of the beginning of its construction from now until well into 2008. As part of this celebration, the cathedral is hosting a special exhibit lasting until October of 2008 called “Dreamers and Believers: Cathedral Builders,” which tells the story of the church with the words and work of those who organized it, financed it, and built it. More than a place of worship, the National Cathedral is a living document of the nation’s history and culture. Three men accepted the mantle of architect of the National Cathedral, knowing they likely wouldn’t live to see its completion.

“Cathedrals do not belong to a single generation,” said National Cathedral Dean Francis B. Sayre Jr. “They are churches of history. They gather up the faith of a whole people ... as they have hoped and suffered and believed, across the centuries.”

A scant 17 years later, we reach the cathedral’s centennial and a time to look back on its journey from vision to reality. After all, “If you compare it to the history of other medieval cathedrals,” says John Runkle, the cathedral’s conservator, “83 years isn’t bad.”

The 150,000 tons of Indiana limestone that sit on Mount Saint Albans in northwest Washington sprung largely from the mind and energies of the Bishop of the District of Columbia, Henry Yates Satterlee. Early designs for the church opted for a Beaux Arts Renaissance style, but Yates (selected as the diocese first Bishop in 1896) was brusque in his objections. “Gothic is God’s style,” he decreed. Runkle, a reverend as well as an architect, calls the cathedral’s design the “crest” of the mid-19th century wave of renewed interest in Gothic style.

With heavens-bound spaceships peering out onto Gothic flying buttresses, all this risks surreality, but the function of the architecture of the cathedral is to transcend and unify all the stories it contains, to render them into mere details in a grand narrative. The simply massive scale of the National Cathedral helps to put this in perspective. Sited 400 feet above sea level on Mount Saint Albans, it lords over all of no-rise Washington, taller than both of the more well-known vertical landmarks of the city, the Capitol and the Washington Monument (which could nearly lie horizontally inside the cathedral). For all its sculpture and glassworks, the cathedral would make a terrible art gallery. The rich texture of the ribbed vaults pull eyes skyward, transfixed by the vast expanses of the nave.

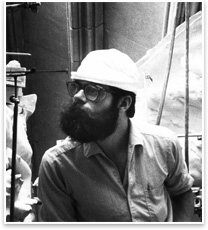

No detail of the cathedral’s history was too small to find some way to be immortalized in it. Many of the stone masons found their faces looking out over the city as grotesques or gargoyles. Carver PatrickPlunkett was rewarded for his years of carving a cathedral out of stone with a fanciful caricature that sports his voluminous beard in the hopes, he said, that the cathedral would be “here for a thousand years.” Nine-hundred to go.

|

||

Copyright 2007 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

Visit National Cathedral Centennial Web site.

Captions

1. The Washington National Cathedral is celebrating its 100th anniversary this year.

2. The first known construction photograph of the cathedral site, circa 1909.

3. President Theodore Roosevelt address a crowd of well-wishers after the cathedral’s cornerstone was laid in 1907.

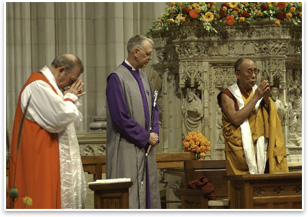

4. His Holiness the Dalai Lama worshipped at the cathedral in 2003.

5. President George W. Bush speaks at the funeral of Former President Gerald R. Ford earlier this year.

6. Cathedral stone carver Patrick Plunkett.

7. Plunkett immortalized.

Photos © Washington National Cathedral.