|

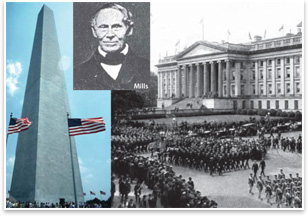

Robert Mills Inducted into the South Carolina Business Hall of Fame

America’s first architect gets some home-state recognition

Penney spoke eloquently of his personal connection to the historic First Baptist Church in his native Charleston, S.C. “I joined … to be dually inspired every Sunday morning—both by the Word and by the architecture in those brief intervals where my mind might wander during the sermon,” he says. Mills, the architect (another native of Charleston), who designed the nearly 200-year-old church, said at the time that it “exhibits the best specimen of correct taste in architecture in the city. It is purely Greek in style, simply grand in its proportions, and beautiful in its detail.” With hometown pride in his heart, Penney received the historic recognition of the legacy when he accepted Mills’ posthumous induction into the South Carolina Business Hall of Fame on May 24. Mills is known as the first native-born American trained in architecture, and was also the first architect to be inducted. The ceremony took place at the Columbia, S.C., Metropolitan Convention Center in front of a black tie-clad audience of 700 South Carolina business community members. The price to pioneer It’s not surprising that America’s first architect would practice in a financially volatile field, and Mills did indeed encounter the problems of a pioneer. He was the first native-born expertly trained architect in an era when there were no academic architecture programs. There was little standardized fee structure for payment, and the early 19th century was rocked by a series of recessions resulting from unstable currency values. But Mills was persistent. The scope of his projects was vast, from small county courthouses in the rural Piedmont region of South Carolina to national monuments in Washington D.C., from his native state all the way to Philadelphia. His civic focus on government work and lack of wealthy private patrons also failed to raise his often lacking finances and historical profile. “Mills certainly viewed architecture as a public service and in that he was very successful,” says John Bryan, Hon. AIA, an emeritus professor of art and architectural history at the University of South Carolina and Mills’ primary biographer. “He looked on buildings as systems to deliver the fruits of democracy.” In his designs for the many civic buildings he completed, Mills became largely responsible for the image of the American courthouse as one of strength and integrity by expertly expressing these values with Greek Revival and Palladian forms, according to Reid Toth, an assistant professor of applied criminology at Western Carolina University. A pragmatist, not a copyist Bryan doesn’t see it that way. He says Mills was a pragmatist, not a copyist, and at odds with Latrobe’s inflexible notions of artistic integrity. Unlike his former mentor, Mills was willing to change a design to suite a patron or fit a budget. “I think Latrobe thought Mills often gave too much away,” says Bryan. To the contrary, Bryan says only Latrobe can truly match Mills in prominence and eclectic talent. In his book, America’s First Architect: Robert Mills, Bryan argues that Mills was a master of many architectural styles of the day, from his Federalist and Neo-Classical federal government buildings to the less-well-known Gothic designs for the Smithsonian Castle on the Mall. “Mills used historical styles like most of us would use a closet full of clothes,” Bryan says. His original design for the iconic Washington National Monument combined a round, Greek colonnade with the Egyptian obelisk now recognizable around the world. The first citizen-architect |

||

Copyright 2007 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design