Transformative Space

Design School Gallery Makes Campus Turn an About-Face

by Zach Mortice

Assistant Editor

Summary: The Juliana Curran Terian Design Center Pavilion, by hanrahanMeyers Architects, reorients it’s adjacent and connected buildings towards a new campus focal point with light, dynamic metal, and glasswork. It references the school’s history of design and the social and economic history of its Brooklyn neighborhood and fosters an environment of creative collaboration. Summary: The Juliana Curran Terian Design Center Pavilion, by hanrahanMeyers Architects, reorients it’s adjacent and connected buildings towards a new campus focal point with light, dynamic metal, and glasswork. It references the school’s history of design and the social and economic history of its Brooklyn neighborhood and fosters an environment of creative collaboration.

How do you . . . use contemporary design solutions to help create a focused, central college campus that encourages interdisciplinary artistic collaboration? How do you . . . use contemporary design solutions to help create a focused, central college campus that encourages interdisciplinary artistic collaboration?

When Thomas Hanrahan, AIA, and Victoria Meyers, AIA, of hanrahanMeyers Architects were tasked with designing the Pratt Institute’s Juliana Curran Terian Design Center Pavilion, they confronted an odd problem for such a well-regarded school of art and design: a campus that wasn’t designed very well. It largely lacked an organized, central campus mall to tie the school together. The brownstone lofts that make up the school were in clustered groups in a busy Park Slope neighborhood in Brooklyn, and Hanrahan says there was little concept of a central campus public space until 25 years ago. The different design schools had set up what Hanrahan calls “cubbyholes” of artistic detachment, separate and isolated from each other.

“The campus had evolved for many years in that direction where it’s just a disparate set of buildings,” he says. “Different programs were scattered on different floors, and people had little fiefdoms.” “The campus had evolved for many years in that direction where it’s just a disparate set of buildings,” he says. “Different programs were scattered on different floors, and people had little fiefdoms.”

A collaborative solution

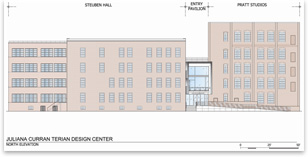

Hanrahan and Meyers responded to this challenge by using the Design Center Pavilion to refocus the adjacent Pratt Studios and Steuben Hall lofts back towards a concrete community focal point and encourage interdisciplinary study and participation among Pratt students and faculty. The 6,000-square-foot metal-and-glass gallery space bridges the narrow area between the two lofts, and its dynamically splayed, overhanging front demands attention and invites visitors up into the multi-media exhibits it holds. The sharp juxtaposition of the brownstone lofts and the sleek steel pavilion point viewers directly towards the developing campus mall. “The most difficult thing was to make a building that is experienced vertically as opposed to horizontally,” says Hanrahan. “It’s intended to draw people up through the building and then connect the classroom buildings horizontally.”

Once inside the Design Pavilion, its architects hope visitors will do more than just gaze at art. One of the primary goals of the project is to facilitate the integration of the Pratt Institute’s four design schools (interior design, fashion design, industrial design, and communications design), which will all use the buildings to create a collaborative focal point where young artists can absorb inspiration from colleagues they might never come in contact with otherwise. Hanrahan says he’s already seen collaborations unfold between several of the design programs and the architecture program, where he’s already heavily invested in the Pratt community. He should be—he’s the dean of the Pratt School of Architecture. Once inside the Design Pavilion, its architects hope visitors will do more than just gaze at art. One of the primary goals of the project is to facilitate the integration of the Pratt Institute’s four design schools (interior design, fashion design, industrial design, and communications design), which will all use the buildings to create a collaborative focal point where young artists can absorb inspiration from colleagues they might never come in contact with otherwise. Hanrahan says he’s already seen collaborations unfold between several of the design programs and the architecture program, where he’s already heavily invested in the Pratt community. He should be—he’s the dean of the Pratt School of Architecture.

Insider understanding Insider understanding

This insider understanding led Hanrahan towards a design that honored the Pratt Institute’s history of embracing contemporary solutions to design problems. One hundred years ago, the adjacent lofts the Design Center Pavilion connects to were considered a new and radical way to approach classroom space. (They were also designed with a tinge of pragmatism, as founder Charles Pratt made the exposed brick, wood frame lofts suitable for conversion to factories, should his art school fail.) Building on this tradition of innovative design, hanrahanMeyers created a rectangular structure that seems to float skyward on top of jogged glass doorway and full-length windows, precariously balanced and impeded between two brawny brownstones. Many of the firm’s projects resemble an ethereal cube, hovering on top of a cloud of light, and in this case the energy trapped by the steel balloon’s wedged and stalled “ascent” is projected with an invigorating force throughout the building.

“We treated the brick buildings as a kind of ground against which the lighter-weight metal worked as a counterpoint,” says Hanrahan.

Meyers continues: “We wanted to float something in the air so that it was very transparent and people felt very comfortable walking into it. Once you float it in the air, it wants to be built like an airplane or something out of metal so it can feel comfortable floating like that.” Meyers continues: “We wanted to float something in the air so that it was very transparent and people felt very comfortable walking into it. Once you float it in the air, it wants to be built like an airplane or something out of metal so it can feel comfortable floating like that.”

The Design Center Pavilion gets its name from Juliana Curran Terian, a Pratt alumna and trustee who donated $5 million to the school. It was completed in December 2006 and was publicly dedicated in April 2007.

Pure Pratt Pure Pratt

The Design Center Pavilion is more than just a renewed commitment to cutting-edge design. It also references Brooklyn’s social and economic history as a former place of industry and shipping (the Brooklyn Navy Yard is nearby) by matching itself with custom-made, hand-rubbed black steel to the heavy black fire escapes and industrial metalwork seen in area buildings, as angular and imposing as an aircraft carrier.

“In many ways, the building has an image and a way of being constructed that talks about the Pratt legacy,” Meyers says. |

How do you . . .

How do you . . .  “The campus had evolved for many years in that direction where it’s just a disparate set of buildings,” he says. “Different programs were scattered on different floors, and people had little fiefdoms.”

“The campus had evolved for many years in that direction where it’s just a disparate set of buildings,” he says. “Different programs were scattered on different floors, and people had little fiefdoms.”