| |

Happy Earth Day: COTE Top Ten Green Buildings

Jury also selects four honorable mention projects

by Heather Livingston

Contributing Editor

Summary: In honor of Earth Day on April 22, the AIA Committee on the Environment (COTE) announces their selection of this year’s Top Ten examples of sustainable projects that protect and enhance the natural environment. The selected projects address significant environmental challenges with designs that thoughtfully weave architecture, technology, and natural systems. This year’s COTE Top Ten include a model single-family home, sustainable master plan and library, two nonprofit headquarters, a school, and a water treatment facility that doubles as a park. In addition, public education of sustainable practices was a key component of most projects.

As testament to the quality of the nearly 100 submissions, the jury also selected four projects for Honorable Mention for the first time since the inception of the COTE Top Ten awards. “There were so many good projects,” says Juror David Brems, FAIA. “We found it very difficult to draw the line. This shows that there is a lot of good sustainable architecture going on in this country right now—and a lot of design excellence here.”

The COTE Top Ten jury considered 10 metrics for each project:

- Sustainable design intent and innovation

- Regional/community design and connectivity

- Land use and site ecology

- Bioclimatic design

- Light and air

- Water cycle

- Energy flows and energy future

- Materials and construction

- Long life, loose fit

- Collective wisdom and feedback loops.

The 11th AIA/COTE initiative was sponsored by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency/ENERGY STAR®, with BuildingGreen Inc. hosting the submission and judging forms. The projects will be honored at the 2007 AIA National Convention in San Antonio, May 3-5.

2007 Top Ten Green Projects

EpiCenter, Artists for Humanity EpiCenter, Artists for Humanity

Boston

Arrowstreet Inc.

Artists for Humanity (AFH) is a nonprofit that works to bridge economic, racial, and social divisions and provide underserved youth with the keys to self-sufficiency through paid employment in the arts. The decision to build green came from the youths working at AFH who wanted a building that would reflect AFH’s values of sufficiency. The EpiCenter is simple and functional, achieving the highest level of sustainability on a tight budget. The first Platinum LEED™-certified building within Boston, it features a 49-kilowatt roof-mounted, grid-connected photovoltaic array that provides all the building’s energy; a natural ventilation system of fans and operable windows that provides a temperate work climate setting without air-conditioning; a concentration of south-facing windows that provides passive-solar heat gain; translucent interior partitions, which make optimal use of daylighting; energy-efficient lighting coupled with automated daylight dimming; a super-efficient heat-recovery system; salvaged building materials reused in unusual applications; building materials with high recycled content; and a rainwater harvesting system. “This project is not just about design and environmental sustainability, but reaching cultural sustainability,” praised the jury.

Global Ecology Research Center Global Ecology Research Center

Stanford, Calif.

EHDD Architects

From the perspective of the Global Ecology Research Center at Stanford University, the most pressing environmental issues are global climate change, biodiversity, and water issues. This focus resulted in a 72 percent reduction in carbon emissions associated with building operation and a 50 percent reduction in embodied carbon for building materials. Proper orientation, exceptional daylighting, sunshading, and natural ventilation set the stage for innovative mechanical systems. The Night Sky radiant cooling system demonstrates the same principles of radiant heat loss to deep space in which the researchers are investigating. A Katabatic Cool Tower serves as an iconic focal point, while tempering an indoor/outdoor lobby and collaboration space. Biodiversity is addressed through a thorough pursuit of salvaged, recycled, and certified materials. The jury said, “LEED ratings were helpful for some of our considerations, but that played out in different ways. In this project, they intentionally opted out of the LEED process to push their own agenda. We appreciated the independent thinking and the explanation about it.”

Government Canyon Visitor Center Government Canyon Visitor Center

Helotes, Tex.

Lake/Flato Architects

Situated in a restored field of native grasses and oaks, the visitor center forms the gateway to the Government Canyon State Natural Area. The design theme was to “touch the ground lightly,” minimizing impact on the landscape and fragile water resources. Extraneous space was eliminated resulting in reduced building materials, energy use, first costs, operations cost, and maintenance. Exhibit and circulation spaces, originally programmed as indoor spaces, were designed as sheltered and shady outdoor spaces, accepting summer breezes and protecting from north winds without air-conditioning (reducing conditioned space by 35 percent). The developed area was concentrated to reduce landscape water use and physical impact on the site. The main exhibit space is built using materials and technology traditionally employed by ranchers in cattle pens and fencing. The stone walls use the same materials and techniques as historic stone fences found on the site. Using such materials and methods not only leads to reductions in embodied energy but also honors the material and construction efficiencies of the local rural traditions. “This has the great Texas vernacular—what the world was like before air conditioning,” praised the jury.

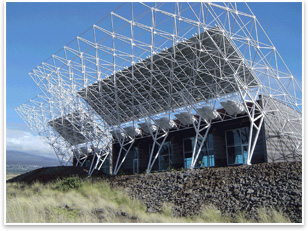

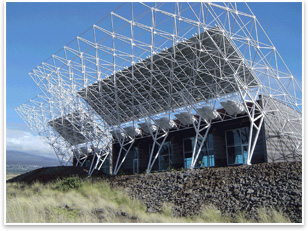

Hawaii Gateway Energy Center Hawaii Gateway Energy Center

Kailua-Kona, Hawaii

Ferraro Choi and Associates

The visitor complex is the “Gateway” to the Natural Energy Laboratory of Hawaii. Reducing the need for human-made energy sources by using building form to harness natural energy systems was the key sustainable strategy. The HGEC is designed to capture heat and create air movement using building form and principles of thermodynamics. The center is designed as a thermal chimney, moving outside air ventilation at 10-15 air changes per hour using the building itself as the mechanical system. The copper roof is the “engine” that triggers a thermo-syphon, radiating heat from the sun into a ceiling plenum. The heated air rises and exhausts through “chimneys” on the north face. The exhausted air is replenished with outside air that is routed across a vented under-floor plenum connected to a fresh air inlet structure. Incoming air is drawn across cooling coils filled with 45-degree Fahrenheit seawater, cooling the air to 72-degrees. As the temperature increases, so does the draw of the thermo-siphon, maintaining a natural balance. The center’s only energy needs are for the deep seawater circulating pump and operations plug loads, more than half of that power is provided by an on-site photovoltaic array that generates 20kWh. Enthused the jury: “This project really uses all of Earth’s devices, then dramatizes that with this visible structure.”

Heifer International Heifer International

Little Rock

Polk Stanley Rowland Curzon Porter Architects Ltd.

A world hunger organization, Heifer’s community impact starts with delivering one animal to one family, known as “passing on the gift.” The gift of an animal creates “concentric rings of influence” radiating through a village as sustainable methods taught to the original family are passed on when the animal’s offspring are gifted. Reflecting its mission, the headquarters’ design was conceived as concentric rings expanding outward from a commons. The aim of achieving zero water leaving the site began a process of restoring a former wetland to collect and clean water for reuse naturally, a solution that received the EPA’s Phoenix Award for Region 6. The interdependence with nature and site is evident in the vertical circulation design and façade fenestration, on-site recycled materials, and carved breezeways under the building, all interrelated with building systems. The narrow arcing plan shifts in a radial pattern, organized by building function to reach 100 percent natural light and views for all 474 employees, focused to the adjacent riverfront park and wetland. The building is designed to use up to 54.9 percent less energy than a conventional office building. “The sustainable features are visible, but not ‘in your face,’” the jury said.

Sidwell Friends Middle School Sidwell Friends Middle School

Washington, D.C.

Kieran Timberlake Associates

The Master Plan for this pre-K-12 school focuses on meeting programmatic needs for its two campuses, including campus unification through development of coherent landscapes and enhanced pedestrian circulation. The addition and renovation to the Middle School transforms a 55-year-old facility while teaching environmental responsibility by example. Built in 1950 to serve 230 students, the Middle School now accommodates 342 students. Additionally, the existing landscape was a biological and aesthetic scar; for instance, all water falling on the site was directed through poorly repaired pipes to the storm sewer system. Providing exceptional integration of curriculum and mission, the plan transformed the landscape into a constructed wetland to process water. Rainwater is retained on a green roof, with overflow directed down a sloped spillway into a biology pond. Beyond the landscape, the configuration of exterior wood sunscreens reveals the building’s orientation and balances thermal performance with optimum day lighting, and at the same time is a formal reference to the forest from which the wood originates. “The building itself is a teacher,” enthused the jury. “It tells the students where they are and helps them be conscious of water and light.”

Wayne L. Morse U.S. Courthouse Wayne L. Morse U.S. Courthouse

Eugene, Ore.

Morphosis and DLR Group

The Morse Courthouse demanded the reconciliation of two seemingly discordant needs: security and sustainability. A Security Level IV facility—one level below buildings such as the Pentagon—this facility entails stringent and complex security requirements. The owner also sought sustainability equivalent to LEED Silver, which posed a unique challenge to the design team: create a building that unites the implied densities of security (thickness, rigidity, separation) with essential values of sustainability (transparency, airiness, sensitivity, connectivity). The team engaged in a concerted effort toward this reconciliation, delivering a building that garnered LEED Gold certification. The design implements innovative strategies to provide building security within a living, breathing, organic design vernacular wrapped around real-world sustainable features: a dramatic, ecologically sensitive transformation of the site; extensive glazing for natural light and connectivity; energy and water-saving systems and fixtures; and an architectural expression of judicial presence at a healthy, human scale. “This is a complex and demanding program,” noted the jury. “Getting the daylight in while dealing with those issues is a very smart response in a complex building type.”

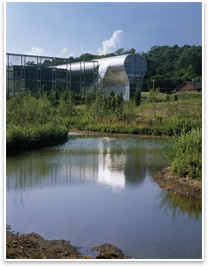

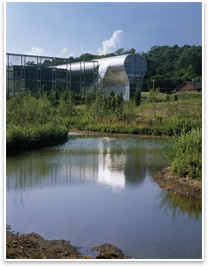

Whitney Water Purification Facility Whitney Water Purification Facility

New Haven, Conn.

Steven Holl Architects

The new facility provides an abundant water supply to south central Connecticut, creates a vibrant watershed ecosystem, and includes a public park and educational facility while providing a diverse habitat and sanctuary for migrating birds. Water purification facilities are located beneath the park (a green roof of 30,000 square feet), while the operational programs rise up in a 360-foot stainless steel sliver expressing the workings of the plant below. Like an inverted drop of water, the sliver creates a curvilinear interior space which opens onto expansive views of the park and surrounding landscape. The interior facilities include an exhibition lobby, laboratories, an acoustically treated lecture hall, conference spaces, and extensive operational facilities. The below-grade location of the process spaces, the thermal mass of the extensive concrete tanks and walls, the high performance insulation of the green roof system, and the geothermal plant of 88 wells minimizes energy consumption. Purifying millions of gallons of water per day, the new Water Purification Facility and Park comprises six sectors, analogous to the six stages of water treatment. “They reinvented the programmatic understanding of a water purification facility by combining it with a park and being really inventive with form-making,” said the jury.

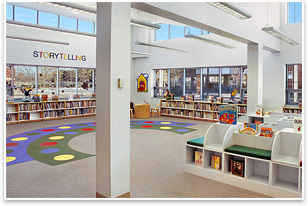

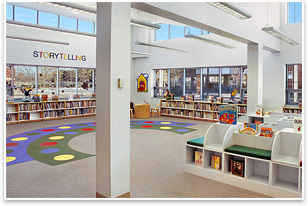

Willingboro Master Plan & Public Library Willingboro Master Plan & Public Library

Willingboro, N.J.

Croxton Collaborative Architects, PC

Willingboro is one of three original Levittowns in America. The project site, developed as Willingboro Plaza in 1959, provided the main retail/commercial tax base for the 33,000 residents until its failure and abandonment in 1990. The goals of this project were to create a consensus Sustainable Master Plan and develop supporting zoning ordinance; pursue an EPA grant for brownfield remediation; and achieve an economic “turnaround” through new development, using as many existing structures as possible. The design of the library addresses its vulnerability as “first on site” in an abandoned area with a history of crime. The dramatic cantilevered entry canopy provides well-lighted and secure pedestrian perimeters and supports the signature marquee. Daylighting is the defining strategy, with the roof incorporating multiple clerestories and major skylights. The gas-fired heater/chiller has no ozone depleting refrigerants and easily transitions to biofuels. Additionally, the sustainable landscape design incorporates vegetated swales, rain gardens, and site reforestation. The jury praised the project as, “a tremendous example of how to make something beautiful and functional out of practically nothing.”

Z6 House Z6 House

Santa Monica, Calif.

LivingHomes, Ray Kappe

The four bedroom, two-and-a-half bath house features bedrooms with movable walls that open up to the public, high-volume core of the house, inviting a flexible use of space when bedrooms are not occupied. The house is constructed of factory-built modules that were delivered to the site and erected in 13 hours. The roof deck takes advantage of the local views and the green roof is planted with native plants. Z6 house was built as a model home for a line of sustainable single-family dwellings, and the commitment to minimize the ecological footprint informed all aspects of design. The philosophy used was “Six Zeroes,” an explicit goal of removing all negative impacts on the environment, the community, and the resident. The goal was zero waste, energy, water, carbon emissions, and ignorance. The design maximizes the opportunities of the mild, marine climate, using passive cooling (cross ventilation + solar chimney), collecting solar energy (2.4 kW photovoltaic in addition to a solar hot water collector), and maximizing daylighting. “This is beautifully crafted and resolved,” the jury said.

|

|