Transforming Design Education in Light of Integrated Practice and Sustainability Summary: In separate events in October 2006 and February 2007, 65 top educators and practitioners were given a challenge: “Design the change between the professional curriculum of fall 2009 and the professional curriculum of today. Develop diagrams to illustrate the difference.” On June 28, 100 top educators and practitioners will gather to build upon that challenge. Please consider registering to attend. Transformed architecture practice will require transformation of architecture education. With accelerating trends of sustainability, technology, and collaboration in practice, we are clearly in a time of rapid transition. This year’s upcoming joint ACSA/AIA Educators Practitioners Network (EPN) Cranbrook Academy will build upon the Integrated Practice Issues Forum of October 2006 and the related AIA Conference on Sustainability in Architecture Education held in February 2007, all intended to inform the National Architectural Accrediting Board (NAAB) Accreditation Review Conference in 2008. Opportunities to influence architecture education deeply are rare, given the NAAB’s five-year cycle of accreditation criteria review. The AIA’s Integrated Practice and Sustainability Discussion Groups, along with the Educator Practitioner Network (EPN) and the Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture (ACSA) are working hard to take full advantage of this event. As a national AIA vice president and last year’s champion of integrated practice, and with my focus this year on sustainability, I’d like to share with you a little bit about what we’ve done—and what we’re doing—to influence the NAAB conversation. The Integrated Practice Issues Forum took place in Frank Lloyd Wright’s Unity Temple in Oak Park last year. Participants presented brief individual opinions on the state of current curriculum, then assembled into five teams, each given the charge you read at the beginning of this article. The diagrams below represent the consensus opinion of each team and are accompanied by a statement of intent. At the California State Polytechnic University in Pomona earlier this year, the AIA Conference on Sustainability in Architecture Education was a slightly larger but identically designed event, with a focus on sustainability in curricula. Proceedings from the Pomona event are being documented and will be available for download in the near future. Cranbrook 2007: Integrated Practice and the 21st Century Curriculum I encourage you to reflect on the outcomes of all three events as they become available and engage in dialogue with your peers and colleagues in practice and education. With careful and thoughtful conversation in both the professional and academic communities, we can ultimately engender transformative practices in schools to better support necessary movement toward sustainability and integrated practice. Outcomes from the 2006 Oak Park Conference Oak Park Team 1

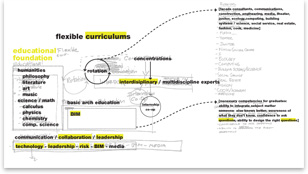

We perceive several areas of expertise within the practice of architecture and propose more flexible professional curricula that is closely aligned with these multiple realities of contemporary practice. By setting up proper mechanisms for student access and exposure to various areas of related knowledge and expertise we can help students to focus and excel on a specific area of interest. Rotations for upper division students in school-specific concentrations will cultivate the diverse knowledge areas, programs, and agencies that characterize contemporary architectural practice. Architects emerging with academic and professional experience in real estate development, façade consulting, building ecologies, building physics, construction management, urban design, political service, non-profit, engineering, facility services, design-build, etc. will better situate the graduates and profession. Oak Park Team 2

Overview: BIM was accepted as a given. Questions arose how to integrate and teach it, but these issues were not addressed. BIM was recognized as a means to various ends, not an end in itself. Discussion focused on making teaching more integrative. Each school of architecture has to balance between providing future architects with an incubator for their self-development and as a workshop to gain skills of collaboration and integration resulting of the benefits of BIM. A useful distinction in curriculum style was between information “push” that lays out information to be learned before the context and problems that the information addressed is outlined, in contrast to education based on “pull,” where students gain an understanding of a problem to solve within a broader context, then gain what they need to learn within the problem context. Architecture programs currently develop projects that address certain issues within the studio setting but generally leave the integration of building technologies, specifications, materials, construction, for the students to integrate themselves. The idea of integrated studios was thought to provide better curricular support for the desired integration, rather than leaving it to the students. Integrated Studios: One major proposal was to eliminate the separation of “push” education in technology courses and the “pull” education in studio, making it all “pull.” Certain studio courses would be integrated with structures, with environmental controls and sustainability, and with materials (materials was thought to be an important topic for architectural education). A broader range of issues was expected to be integrated beyond the standard technology courses. The new ones included cost control and management, scheduling and very fast building strategies, broader sustainability issues of transport, material waste, construction practices, etc. beyond energy. This means re-thinking how technology courses are taught and the staffing means to support studio-based technology education. It means that the organization of studio and teaching and review is dramatically changed to adopt to this new content. It was assumed that this mode of education did not eliminate the development of base principles in technology areas, but they were approached “top down” as the basis for approaches, not taught from the bottom up. There was also discussion of the implication for such collaborative teaching, with regard to promotion and tenure. It was thought that to realize the complex objectives in studios, design problems might become more fixed and repeated, so that background materials and a rich context for these courses could be developed. Several schools were doing the Solar Decathlon or did so previously. It was thought of as an excellent example of an integrative studio. Other proposals dealt with Integrated Practice across departments and schools. Schools with City Planning and Building Construction were thought to have large advantages over those that did not. Studios based on Design Teams: Another topic of discussion dealt with specialization within design. Designing curricula for small office practice and only generalists was thought to be a trap both for the profession as well as for students. If students cannot excel in design conceptualization, then they often quit architecture. However, there are many related roles: focusing on lighting, complex building skins, structures, fabrication, materials research, sustainability and so forth. It was proposed that students needed to experience developing design concepts within collaborative team approaches, where students for the period of a semester would take on specialist design roles. Some workshop participants referenced medical school, where all students learn common core materials, then do “rotations” in different clinical areas, as a way to learn how different areas of medicine operate. Oak Park Team 3

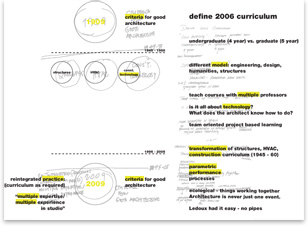

Our proposal for the curriculum of 2009 begins with the observation that the format of our current teaching was only developed in the late 1940s and early 1950s, and was suited to the particular characteristics of that time. The division of building technology into three courses on Structures, Construction, and Environmental Systems arose in response to a precise historical situation, that refined mathematical theories had been developed for structural analysis, that new kinds of environmental devices like air conditioning were becoming increasingly common, and the means and methods of construction were being transformed by new materials and new business relationships. Moreover, architectural education had just completed the transition from the office apprenticeship to formal educational settings, and so a kind of learning that fit into semesters and course units had to be rapidly developed. In contrast, we described the curriculum of 2009 as a reintegrated form of practice, bringing technological topics back into the design studio and able to accommodate different forms and modes of design research. We called that format “curriculum as required” to explain the degree to which it would be studio and project based, drawing on multiple forms of expertise and providing multiple forms of experience. This new condition would operate differently in the undergraduate, graduate, and apprentice phases of education, and might also blur them, allowing for further forms of integration, for learning by teaching and by doing. The final configuration might best be described as ecological, in which everything works together, and will be familiar to any general practitioner. The particular developments of virtual construction modeling were specifically understood as a re-intensification of longstanding aspects of architectural design, of the parametric modeling of formal and conceptual relationships, of the performance evaluation of design results, and of close attention to the processes of design. Oak Park Team 4

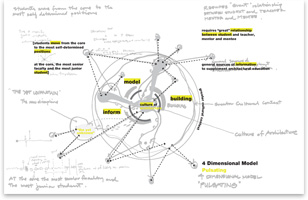

Building: This area encompasses an intense study of making buildings. It elevates the importance of understating how buildings go together and focuses on developing the skills necessary to choreograph and integrate complex systems in building design. Modeling: This area of study includes developing the skills necessary to model buildings and design. It considers modeling in the broadest sense to support multiple perspectives including economic modeling, 3-D modeling, energy modeling, database modeling, etc. Information: This portion of the curriculum concentrates on navigating, organizing, and parsing the massive amount of information necessary to make buildings and includes information ranging from historical precedent to contemporary technology trends. The three broad areas of the curriculum represent a tripartite platform built on a strong cultural foundation from which an architectural education may be constructed. Faculty and students work together to plot a course that moves them from an intense relationship with senior faculty early in their education to positions of leadership and collaboration. Along the way, faculty help students identify expertise and encourage them to capitalize on individual strengths. Oak Park Team 5

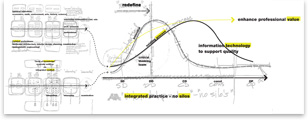

We made a distinction between BIM and IP:

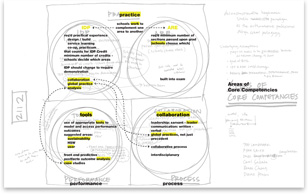

Each has the potential to bring either evolutionary change or revolutionary change. Each is the inverse of the other depending on if you are looking at change in practice or change in education. Changes needed for schools to address IP are different than those needed for BIM—this is the difference between revolution and evolution. Response to IP will require developing a shared set of values among the collateral organizations and individual schools, and significant change to accreditation and internship. Educators must challenge the very heart of our shared values – the design studio. While design remains central, critically important for studio and other courses are "collaboration core competencies": ability to work successfully in interdisciplinary creative teams, write and speak effectively on professional topics, and to be skilled in the arts of negotiation and facilitation. An important message is “keep our eyes on the prize”: design thinking has enormous value – it is our expertise. To succeed, schools must: In context of IP, create holistic, systemic, revolutionary change

In context of BIM, evolve day-to-day curricular experiences:

|

||

Copyright 2007 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

The Oak Park team would like to thank Daniel Friedman, FAIA, for his extraordinary efforts in organizing this process.

Registration for the conference opens April 6. For more information, visit the ACSA Web site.