7/2006

by Lt. Jim Vandenberg, AIA, CEC, USN

After design work for the U.S. Marines in Iraq, I recently returned from a six-month tour of duty as the architect for civil projects in the Sulu archipelago in the Philippines for Operation Enduring Freedom. I normally work as the architect for Arkansas State Parks, but most recently have helped the Joint Special Operations Task Force–Philippines (JSOTF-P) as their lead “engineer.”

It

was an island-hopping campaign to build economic capacity with schools,

clinics, community centers, roads, and water distribution projects on

three large islands and about a thousand smaller ones. The concept is

to work with the local civil authorities to determine needs, then program

and design specific projects. As combatants against a local insurgency,

we coordinated with Special Forces in the Sulu archipelago in the southern

Philippine chain, including Jolo and Tawi Tawi—the gateway between

lawless areas of Indonesia and Malaysia teeming with terrorist training

camps. It is through architecture and construction that we intend for

the economic conditions of this Muslim area to improve steadily.

It

was an island-hopping campaign to build economic capacity with schools,

clinics, community centers, roads, and water distribution projects on

three large islands and about a thousand smaller ones. The concept is

to work with the local civil authorities to determine needs, then program

and design specific projects. As combatants against a local insurgency,

we coordinated with Special Forces in the Sulu archipelago in the southern

Philippine chain, including Jolo and Tawi Tawi—the gateway between

lawless areas of Indonesia and Malaysia teeming with terrorist training

camps. It is through architecture and construction that we intend for

the economic conditions of this Muslim area to improve steadily.

Our team devoted a majority of our time designing and managing construction on $3.7 million in community development projects. Our second program was to develop the U.S. forward-operational base infrastructure to extend the JSOTF-P presence across the 200-mile Sulu archipelago.

In 2004, I was in Iraq as project manager of Iraqi Security Forces (ISF)

construction. This included 32 border forts on the 890 kilometer border

of Syria, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia. (Read

the article describing that work.) Movement to these sites was difficult. Because of ambushes,

plus time and distance constraints, we had to go on week-long patrols

and day hops in combat helicopters with the U.S. Marines. In the Philippines,

similar hardships and distances had to be traversed, but instead of

sand, it was the open sea and inlets that stood between us and construction

inspections.

In 2004, I was in Iraq as project manager of Iraqi Security Forces (ISF)

construction. This included 32 border forts on the 890 kilometer border

of Syria, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia. (Read

the article describing that work.) Movement to these sites was difficult. Because of ambushes,

plus time and distance constraints, we had to go on week-long patrols

and day hops in combat helicopters with the U.S. Marines. In the Philippines,

similar hardships and distances had to be traversed, but instead of

sand, it was the open sea and inlets that stood between us and construction

inspections.

For

a week in December, we were accompanied by an armed unit of Philippine

Marines and U.S. Navy Seals on an island-hopping visit to assess the

condition of schools in the Tawi Tawi island group. Visiting two to

three islands a day, crossing rough seas in an open six-meter boat, we

visited 12 villages on 11 islands, and traveled to within 10 miles of

Malaysia, assessing conditions.

For

a week in December, we were accompanied by an armed unit of Philippine

Marines and U.S. Navy Seals on an island-hopping visit to assess the

condition of schools in the Tawi Tawi island group. Visiting two to

three islands a day, crossing rough seas in an open six-meter boat, we

visited 12 villages on 11 islands, and traveled to within 10 miles of

Malaysia, assessing conditions.

In the majority of locations, the schools were about to collapse, with

concrete spalling off rusting rebar in columns and walls. On Sitangkai

Island—also known as “water world”—18,000 people

live in stilt shacks over the water. The island’s two high schools

occupy the only land mass, the size of a city block.

In the majority of locations, the schools were about to collapse, with

concrete spalling off rusting rebar in columns and walls. On Sitangkai

Island—also known as “water world”—18,000 people

live in stilt shacks over the water. The island’s two high schools

occupy the only land mass, the size of a city block.

Under these conditions, we developed three building types meant to make people’s day-to-day lives better.

Project Type 1: Area Coordination Center (Community Centers)

The concept of an area coordination center had been established in the

Joint Operational Area (JOA) during the eradication of insurgents on

the island of Basilan in 2002. But no standardized design had taken

it further than a programmatic stage. Using the standard footprint

of an 8x10-meter classroom, a plan was developed in November and further

refined by January. The first construction project used four steel

reinforced concrete frames with block infill structures arranged around

an open space large enough for a basketball court, the most popular

sport in the archipelago.

Two

long shed buildings created the long sides of the courtyard. One function

is an indoor market hall with the flexibility to be used as classrooms

or meeting rooms. The other, an open market shed, could be closed in

to create more indoor space. On the short ends was a high roof storage

building for use in times of need or disaster, and the other was a low

building containing two offices and men’s and women’s

restrooms on the outside flanks. The design takes into account the local

use of poured concrete, with wood or steel trusses spanning the column-less

space. We opted for a prefab panel system that allowed quick forming

of poured-in-place concrete walls. The roof material was locally purchased

corrugated galvanized painted steel panels. There were no windows with

glass, as they don’t survive the environment and people in the

area. Instead, wood jalousie windows were constructed inside the wall

openings. Doors are solid wood. All work is done on site, by hand. The

ceiling consists of 4 x 8 sheets of painted plywood. Lighting is minimal

and air circulation is by ceiling fans.

Two

long shed buildings created the long sides of the courtyard. One function

is an indoor market hall with the flexibility to be used as classrooms

or meeting rooms. The other, an open market shed, could be closed in

to create more indoor space. On the short ends was a high roof storage

building for use in times of need or disaster, and the other was a low

building containing two offices and men’s and women’s

restrooms on the outside flanks. The design takes into account the local

use of poured concrete, with wood or steel trusses spanning the column-less

space. We opted for a prefab panel system that allowed quick forming

of poured-in-place concrete walls. The roof material was locally purchased

corrugated galvanized painted steel panels. There were no windows with

glass, as they don’t survive the environment and people in the

area. Instead, wood jalousie windows were constructed inside the wall

openings. Doors are solid wood. All work is done on site, by hand. The

ceiling consists of 4 x 8 sheets of painted plywood. Lighting is minimal

and air circulation is by ceiling fans.

In

almost every village visited, there was no power generation unless the

mayor, or some other politically connected tribal leader, had a gas-powered

generator. Water is caught from the sky and kept in concrete cisterns.

Much of our infrastructure emphasis was drilling water wells and building “fish

to market” roads to connect villages. The largest island we worked

on was Jolo, the heart of the Islamic insurgency. Most other islands

were smaller and did not have roads or vehicles. There were very few

hardened structures on most islands. Typically, only the school was a

permanent building.

In

almost every village visited, there was no power generation unless the

mayor, or some other politically connected tribal leader, had a gas-powered

generator. Water is caught from the sky and kept in concrete cisterns.

Much of our infrastructure emphasis was drilling water wells and building “fish

to market” roads to connect villages. The largest island we worked

on was Jolo, the heart of the Islamic insurgency. Most other islands

were smaller and did not have roads or vehicles. There were very few

hardened structures on most islands. Typically, only the school was a

permanent building.

There is no to little civil authority. No police, no firefighters, no gas stations, no stores. Most people barter for goods. Since there was no water distribution systems there were conversely no sewer systems. Most huts where people lived were built above the ground to keep the floor well away from insects and vermin. Sanitation was a hole cut in the floor and a pit below or the ocean. The first-order effect was to establish water points where people can fill up their containers, then to have villagers assist with extending water via pipelines to different parts of a village or to a neighboring community.

These ACCs will provide a village center in conjunction with new or

existing schools to establish a sense of place and permanence. They are

a place for the community to gather and create economic ability to sell

fish and agricultural products. This will allow the people of the villages

and Barangay to earn money from goods and create a class of people with

disposable income.

These ACCs will provide a village center in conjunction with new or

existing schools to establish a sense of place and permanence. They are

a place for the community to gather and create economic ability to sell

fish and agricultural products. This will allow the people of the villages

and Barangay to earn money from goods and create a class of people with

disposable income.

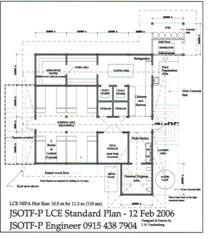

Project Type 2: Liaison Coordination Element (LCE)

This project went from an early-designed concrete block house

that no villagers could afford to a standardized indigenous dwelling—the “Nipa

Hut.” Standard local construction was to use bamboo, smaller

local trees or ‘coco’ wood cut with chain saws to create

4 x 4 major framing members. Huts were basically post-and-beam construction

that are three three-meter bays per side. Sloped thatched roofs included

the “Muslim Gable” to catch and direct breezes and infill

panels of Salawi material similar to pressed interwoven bamboo, which

is fashioned into sheets. JSOTF-P’s goal was to blend these structures

in and mix more readily with local construction using the same materials.

The military advisor teams moved frequently as the mission dictated.

The huts had to be lightweight construction, inexpensive to build,

assembled quickly and if vacated would be a good local house a

family could move into.

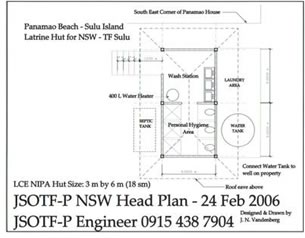

Project Type 3: Base Operations and Support Projects (BOS)

Project Type 3: Base Operations and Support Projects (BOS)

Sanitation is one of the primary necessities that often is hard to come

by in a jungle environment. To improve the quality of life, we designed

and constructed comfort rooms or “CRs,” as they are called

in the Philippines. By designing a modular and easily constructible

facility, the hope is to bring better sanitation and reduce the instances

of disease among the people of the archipelago.

Method of contracting for projects

Method of contracting for projects

The JSOTF-P had to use contingency contracting to accomplish the mission

in an expeditionary combat environment. The following is the methodology

we used to contract construction services from the local Filipino contractors.

1. Work with identified agency, local civil authorities, government representatives, or U.S. government agency to establish the requirements for the proposed project. Often, the civil affairs officer identifies the project based on field operatives’ reports of community needs.

2. The engineer working with Special Forces joint staffs—such as future operations (J5), logistics (J4), and intelligence (J2)—synchronizes projects to fit the mission. The engineer may be sent on assignment to assess an area for potential projects, working with civil authorities and host nation liaisons to visit the various locations. The engineer writes the assessments, documents with photographs, and fills out the target cards for the J5 target board. During the site assessment we try to understand the constraints of the site and the environmental issues affecting the work:

- Are projects easy to get to?

- Are there accessible roads, ports, airfields, and landing zones?

- Are opposing forces operating in the area? Is the area dangerous?

- What is the support from the local population?

- How will workers get materials?

- Where will workers come from?

- What knowledge do local hires have regarding basic manual labor?

- What supervision do local nationals need?

- What is the available infrastructure, clean water, electricity?

- Where do we procure raw and finish construction materials?

3. The target board assembles all target card nominations and, during the target-board with military intelligence input, “racks and stacks” the projects based on the need to get U.S. forces in an area to assist with new construction of vital infrastructure.

4. Once a project has been prioritized, a cost estimate and statement of work (SOW) is prepared. This information is forwarded to Naval Facilities Command, the executive agent to process the bidding process—we then begin to write bid documents and set up a pre-bid conference that asked:

- Is there an approved design or SOW for the project?

- Is it a standardized design?

JSOTF-P Engineer creates three standard design projects including SOWs, cost estimates, and contract documents for the community center, liaison coordination element team houses, and schools. This is an effort to reduce delivery time from project identification to start of construction.

5. There is a Pacific Command Project development flow chart, a guide to direct efforts, involving:

- Issues with construction in the Philippine Joint Operational Area

- Challenges of distance between project sites

- Methods to get there; in the Philippines, it is via boat, helicopter, or airplane because of the number of islands to visit.

6. We have to have a contract, specs, and schedule-of-values forms if a project is custom or non-standard.

7. It is necessary to design infrastructure or civil works, if required, which often is the case since most of the projects are only in the programming phase and need further design to make them constructible in this environment.

8. We have to develop a bidding process encompassing:

- Bid awarding

- Construction inspection

- Construction management/administration

- Periodic payments, which fall under the JSOTF-P Tactical Engineer as an extension of contracting officer technical representative duties.

9. Construction administration and observation is a difficult part as it requires an armed escort into insurgent strongholds to talk to the contractor and the workers.

The civil-affairs construction process in the Philippines is proving very successful. The people of the Sulu archipelago are the winners in this operation and economic growth and security are improving day by day.

One thing the military forces brought to bear was a combat capacity to secure an area devoid of any civil authority and law enforcement. Like the Seabees of World War II, the engineers were able to provide construction capability that a government ministry, non-government organization, or even a civilian contractor could not. The military architects and engineers could construct in an impermissive environment of violence and threats. Once basic security is developed, more investment in capital and construction can follow, eventually bringing civil authority and law.

Copyright 2006 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()

![]()