6/2006

Green architect William McDonough calls for new tools and leadership in sustainable design

“One hallmark of an architectural education is the ability to shift scales: We can view the world differently, depending on where we stand,” said Architectural Record Editor in Chief and Editorial Director of McGraw-Hill Construction Robert Ivy, FAIA, as he introduced the closing session speaker of the AIA national convention on June 10. “One architect among us has enlarged the range of perspective from the minutely small, at the level of the molecule, to the whole planet, challenging us to reconsider our notions of time as well.”

Introducing

William McDonough, FAIA, Ivy said, “In leading the

profession, he employs the classic skills, including rhetoric, the art

of persuasion, to literally change the world. He has articulated

a position, what we today call sustainability.” Ivy noted that

with $3 a gallon gasoline and world-wrenching environmental disturbances,

all of us—professionals and clients alike—are concerned and

motivated to change. “Sustainability has evolved from the protective

purview of a special granola few to the intelligent way to design. The

effective spokesperson for this development is not a politician, but

an architect.”

Introducing

William McDonough, FAIA, Ivy said, “In leading the

profession, he employs the classic skills, including rhetoric, the art

of persuasion, to literally change the world. He has articulated

a position, what we today call sustainability.” Ivy noted that

with $3 a gallon gasoline and world-wrenching environmental disturbances,

all of us—professionals and clients alike—are concerned and

motivated to change. “Sustainability has evolved from the protective

purview of a special granola few to the intelligent way to design. The

effective spokesperson for this development is not a politician, but

an architect.”

Design for the living?

“I would like to make a point of honoring the people with whom

I work—including Kevin Burke, AIA; Mark Rylander, AIA; and Diane

Dale.” McDonough

said. He also paid homage to Thomas Jefferson, our only architect president.

When McDonough served as dean of the architecture school at the University

of Virginia, he said, he had the privilege of living in a residence designed

by Jefferson. It was an extraordinary experience, he said, “because

you realize that Jefferson considered himself foremost a designer.”

That also is evident in Jefferson’s last design: of his own tombstone, McDonough said. He included on it only three of his myriad accomplishments, and they all were things he designed: the Declaration of Independence, Virginia’s Statute of Religious Freedom, and the University of Virginia. It’s interesting, McDonough noted, that he didn’t include two terms as president of the United States! Jefferson’s eloquence recorded for all posterity the fundamental human rights of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” Moreover, McDonough said, Jefferson believed that earthly resources belong to the living, and it is our responsibility to leave to the next generation, when our lives are through, at least as much as we started with.

First signal of human intention

First signal of human intention

“As architects, we need to ask whom are we designing for—the

dead or the living?” McDonough declared. “Design is the first

signal of human intention. So, what is our intention as a species? We’ve

reached the point of evolution where we can decide what happens next

to the planet.”

McDonough and his team believe that to be responsible, “we must love all the children of all species of all time.” How do they strive to do this? The firm begins all projects by reaffirming their goal: “A delightfully diverse, healthy, and just world, with clean air, water, soil, and power—economically, equitably, ecologically, and elegantly enjoyed.”

At a recent meeting at the White House, the noted architect was asked his opinion of nuclear power. He replied that he was all for it, especially fusion. He just thanks God that the reactor is 93 million miles away, offers free energy that can reach us in about eight minutes, and is totally wireless. The point is, he says, we need an end game. “The climate tragedies of our time are of our making.”

Toward a green architecture

McDonough offered a brief history of the events that have shaped his

thinking and practice. Born in Tokyo and raised in Hong Kong, he grew

up experiencing a way of life with an intimate relationship to the

land and a very tight equation between nutrition and waste. Childhood

summers in Seattle and later attendance at an affluent high school

in Connecticut showed him a different life of waste and affluence.

He studied Modern architecture at Yale in Brutalist architecture. When

he graduated in 1969 and saw the Apollo-mission photographs of earth, “away

went away,” he said. It was no longer acceptable to him to throw

things away. “Where is ‘away’ anyway?” he asked.

He opened his own firm, and the Environmental Defense Fund Offices in New York City was his first project. In 1989, he designed a skyscraper in Poland, incorporating as an integral part of the project the planting of enough trees to counterbalance the energy use of the building. Soon after, he designed a daycare center in Frankfort that was a “building like a tree,” that could take in and nourish with rainwater and sunlight. In 1991, he wrote the “Hanover Principles: Design for Sustainability,” which guided the design of the 2000 World’s Fair in Hanover, Germany.

Growth is good

Growth is good

While designing the daycare center, he said, McDonough began to wonder

what was in the building and furnishing materials, noting that the

kids would put their mouths on everything. It was the impetus for development

of his “cradle-to-cradle” strategies, which analyze down

to the molecular level the materials in the products we use—not

just cradle to grave (manufacture to disposal)—but from creation

to re-creation through complete cyclical reuse. In 2002, he wrote Cradle

to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things, with chemist Michael

Braungart, which essentially calls for a revolution—not evolution—in

the way goods are manufactured to eliminate waste and thus perpetually

create resources. “Being less bad is not being good,” McDonough

exhorted. “The environmental movement has not caught on, because

it’s still about being less bad. We’re going to have to

develop new tools to discover what 100 percent sustainable means

for business. This is called leadership—in leadership,

growth is good.”

McDonough explained that Nobel Prize-winning chemist Francis Crick, the discoverer of DNA, said that living organisms need three things to be alive: growth, a free form of energy, and an open operating system of chemistry (i.e., a metabolism) to support the organism. “But what do we want to grow?” McDonough asked. “We want biology to be celebrated for its diversity, but not technical diversity,” he said. “We need to design healthy, safe things from the molecular level up.”

McDonough and his firm designed a fabric for Steelcase in 1993, which was chosen by Airbus for use in its planes. “It’s the safest fabric on the planet,” McDonough said. “You can eat it. The water coming out of its manufacturing mill is as clean as the water going into it. The manufacturer, Shaw Industries, will recycle the carpet when you’re done with it.”

The firm can now analyze the composition of some 6,000 chemicals. They

are taking on the design of greeting cards (which Shaw recycles into

carpet), as well as working with Nike toward recyclable sneakers (you

bring the old pair in when you buy your new pair), and with Ford to create

the Model U, a car based on cradle-to-cradle principles.

The firm can now analyze the composition of some 6,000 chemicals. They

are taking on the design of greeting cards (which Shaw recycles into

carpet), as well as working with Nike toward recyclable sneakers (you

bring the old pair in when you buy your new pair), and with Ford to create

the Model U, a car based on cradle-to-cradle principles.

Sustainability in action

McDonough presented a number of his firm’s projects—many

of which are award-winning buildings that were familiar to the audience—which

use these principles, including:

• The Herman Miller Building, Holland, Mich. (1995): Productivity in this plant doubled, McDonough said. And resource savings paid for the building in four months.

• Gap Building in San Bruno, Calif., (1999): The firm worked with

Gensler as the executive architect. Its roof emulates the area’s

native savannah; the architects secured the native-plant seeds from

federal land. Its raised floors allow free circulation of outside air.

• Gap Building in San Bruno, Calif., (1999): The firm worked with

Gensler as the executive architect. Its roof emulates the area’s

native savannah; the architects secured the native-plant seeds from

federal land. Its raised floors allow free circulation of outside air.

• Nike European Headquarters, the Netherlands (1999). The firm won the design competition by submitting no entry. “If we designed a building without looking at your site or meeting you, that would be arrogant and stupid. Why would you hire anyone arrogant and stupid?” McDonough told Nike. They got the commission and got their subsequent design approved in two weeks and the project built it in two years. Nike expected the approval process alone to take two years.

• Adam Joseph Lewis Center for Environmental Studies at Oberlin

College, Oberlin, Ohio, (2001): This project is designed for chemically

sensitive students. McDonough reports that the building is used twice

as much as they originally thought it would be.

• Adam Joseph Lewis Center for Environmental Studies at Oberlin

College, Oberlin, Ohio, (2001): This project is designed for chemically

sensitive students. McDonough reports that the building is used twice

as much as they originally thought it would be.

• Ford Rouge Center Plant and Master Plan, Dearborn, Mich., Plant: This 20-year project uses native plants as its roof cover. The designers got the commission by showing their water bio-treatment could save Ford $35 million from day one over the cost of conventional systems, which got Ford Board approval in one minute, McDonough said.

• The NMSI Wroughton Natural Collections Centre Project, Wroughton, U.K. This project, currently on the boards, turns a World War II airfield into an artifacts storage center, museum, and elder hostel—replete with sheep on the roof. A lightweight catenary structure uses soil/grass roof as ballast as part of its cradle-to-cradle design.

Practicing design humility

Practicing design humility

“We need to recognize that building design and natural design are

the same thing.” McDonough said. He reported that his firm has

many other projects on the boards that embody these principles. In all

of our work, we need to recognize the concept of “design humility,” he

told the audience. “We need to realize that it took us 5,000 years

to put wheels on our luggage. We’re not that smart.”

Is it right to worry about changing weather patterns and global warming produced by our current design, building, and manufacturing processes? “We’re not worried enough,” McDonoughexhorted. Some 40 percent of the carbon produced by humans since 1850s is now in our oceans. This has decreased the ocean’s pH from its natural 8.8 to 8.2, and it is projected to reach 8.0 by the end of the century. At 7.9, the coral reefs will dissolve. “If design is our intention—do we intend to change?” McDonough asked. “What are the changes we intend to make? And how do we intend to change?”

China is our future

China is our future

These notions bring us full circle to China, McDonough noted. If they

adopt the current manufacturing processes we use, they will toxify

their country, and sell the toxic goods to us. And, since we’re

giving them all of our money for goods, that’s not a sound business

strategy. The first law of business is “do not destroy the client,” McDonough

said.

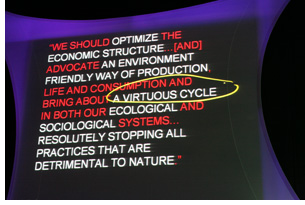

On the other hand, if they make cradle-to-cradle goods, McDonough said, everyone wins. The country has adopted the cradle-to-cradle principles as their national industrial policy. The president of China has declared the necessity of a nationwide “virtuous cycle,” which is the Chinese translation of “cradle to cradle,” and is committed to “resolutely stopping all practices that are detrimental to nature.”

In the residential arena, McDonough explained, China will need to house 400 million people in the next 12 years, and if they use “business as usual” design, they will lose 25 percent of their farmland.

He

presented his firm’s design for an extension of the city of

Luizhou, where sewage will be sold as fertilizer, methane will be burned

to supply 20 percent of the cooking fuel, and direct solar collectors

will provide cladding and supply power. Most remarkable, soil from the

existing farmland site will be lifted and placed on all the roofs of

the city’s buildings, so the farmland will be preserved. McDonough

reported that the master plan was approved six months ago, and Luizhou

will serve as a national demonstration project

He

presented his firm’s design for an extension of the city of

Luizhou, where sewage will be sold as fertilizer, methane will be burned

to supply 20 percent of the cooking fuel, and direct solar collectors

will provide cladding and supply power. Most remarkable, soil from the

existing farmland site will be lifted and placed on all the roofs of

the city’s buildings, so the farmland will be preserved. McDonough

reported that the master plan was approved six months ago, and Luizhou

will serve as a national demonstration project

It’s not hard for his firm to know what to do, McDonough concluded. They have an end game, because, “Our goal is a delightfully diverse, healthy and just world—with clean air, water, soil, and power—economically, equitably, ecologically, and elegantly enjoyed.”

Copyright 2006 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()

Photos by Aaron Johnson,

Innov8iv Design

Incorporated.

![]()