6/2006

Speakers define new roles, new thinking in infrastructure design

At the Friday June 9 general session of the AIA national convention, McGraw-Hill Construction President and American Architectural Foundation Board of Regents Chair Norbert W. Young Jr, FAIA, introduced a terrific trio of speakers who tackled “Engagement,” that day’s topical theme. “Today’s focus, engagement, brings creativity down to earth. It brings our profession’s visions and dreams to the busy intersection where ideas meet the complex reality of politics. How to negotiate this intersection without a costly backup or, worse, a flaming wreck?” Young asked. “This morning’s theme presentations respond to the fact that increasingly we as architects are playing a vital and visible role in shaping our nation’s public infrastructure.”

At the Friday June 9 general session of the AIA national convention, McGraw-Hill Construction President and American Architectural Foundation Board of Regents Chair Norbert W. Young Jr, FAIA, introduced a terrific trio of speakers who tackled “Engagement,” that day’s topical theme. “Today’s focus, engagement, brings creativity down to earth. It brings our profession’s visions and dreams to the busy intersection where ideas meet the complex reality of politics. How to negotiate this intersection without a costly backup or, worse, a flaming wreck?” Young asked. “This morning’s theme presentations respond to the fact that increasingly we as architects are playing a vital and visible role in shaping our nation’s public infrastructure.”

Day: Aviation infrastructure needs architects

Kim Day, AIA, an architect with more than 25 years of experience in all phases of design and implementation on aviation projects, spoke about airports as an integral part of our infrastructure. Until last fall, Day was the executive director of Los Angeles World Airports, a system of four airports owned and operated by the City of Los Angeles, at which she was responsible for 3,000 employees and a $952 million annual budget.

Day pointed out that airports, a relatively new building type, currently are poised on the verge of metamorphosis. Their impact on the economy is enormous—Los Angeles International Airport (“LAX”) generates 60,000 jobs and $160 million annually for the region. The environmental impact of the world’s 1,600 airports is of course significant; much of the air pollution they generate comes from the cars and trucks that service them, not the planes.

Day pointed out that airports, a relatively new building type, currently are poised on the verge of metamorphosis. Their impact on the economy is enormous—Los Angeles International Airport (“LAX”) generates 60,000 jobs and $160 million annually for the region. The environmental impact of the world’s 1,600 airports is of course significant; much of the air pollution they generate comes from the cars and trucks that service them, not the planes.

The former executive director of LAX talked about three models of airports: regional (such as Los Angeles’ John Wayne), large hub (such as Denver or Dallas-Fort Worth), and international gateway (such as LAX). All of these models had the same kind of community impacts—in different levels—on economic benefits, noise, traffic/transit, height limitations, and safety and security. She spoke also about her experience with Southern California’s regional airport system, which currently is concentrating on connecting light rail to LAX, enhancing ground access to all regional facilities and increasing public awareness and ease of use of this option, and promoting the role of LAX in the regional economy.

The former executive director of LAX talked about three models of airports: regional (such as Los Angeles’ John Wayne), large hub (such as Denver or Dallas-Fort Worth), and international gateway (such as LAX). All of these models had the same kind of community impacts—in different levels—on economic benefits, noise, traffic/transit, height limitations, and safety and security. She spoke also about her experience with Southern California’s regional airport system, which currently is concentrating on connecting light rail to LAX, enhancing ground access to all regional facilities and increasing public awareness and ease of use of this option, and promoting the role of LAX in the regional economy.

Only after World War II did airports become economically important, Day reminded the audience, and it is interesting to note how changes in the industry have transformed what originally were long, low civic buildings. The Jet Age began in the 1960s, and Eero Saarinen’s TWA Terminal at New York’s Kennedy Airport and Dulles Airport outside of Washington, D.C., served as the “poster children” for this age. Jumbo jets appearing in the 1970s brought with them more severe environmental impacts in terms of air quality and noise. Recent projects, Day said, show the return of terminals as civic buildings.

However, the dominant design element these days is security. No industry was as devastated by the impact of the 9/11 terrorist attacks than the airport industry, Day said. A completely new paradigm of security, coupled with the growth of low-cost carriers, has created a need for a new terminal prototype. Issues that need to be considered include: security, access/wayfinding, advances in technology, passenger processing, efficiency/flexibility/capacity, new aircraft under development, growing markets, and sustainability/adaptability/reuse.

As an industry facing great challenges, aviation infrastructure needs help from the architectural community,” Day said. “We can be the professionals who prepare this vital industry for a successful future.”

Taylor: It’s about urbanism, infrastructure, commitment

Taylor: It’s about urbanism, infrastructure, commitment

Marilyn Taylor, FAIA, partner-in-charge of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, specifically Urban Design and Planning/Airports and Transportation, spoke about the architect’s role in today’s urbanism. Currently national chair of the Urban Land Institute, Taylor has served as president of AIA New York and chaired the New York Building Congress. She also serves on the boards of the Institute for Urban Design and Downtown Alliance and is an advisor to NYC 2012, City Institute at the University of Pennsylvania, and the Fellows Committee of the Partnership for New York City.

Taylor offered three important themes for engagement:

Taylor offered three important themes for engagement:

1. Urbanism: The AIA convention offers a great and timely opportunity to explore urbanism in Los Angeles and for architects to engage in greater issues of our time, Taylor said. In 2007, for the first time, more than half of the world’s population will live in cities. Projections show further, she said, that in 2015, 15 cities will have populations of more than 8 million people (the size of New York City today). Density issues play as important a part as size; for instance, Hong Kong is three times as dense as New York City.

Taylor said she felt fortunate that her home town of New York City understands the importance of cities and the urban fabric. As an example, she used SOM’s AOL Time Warner Center project, which offers “a vivid mix of uses.” The project works, she says, because of the inclusion of two jazz halls as well as a Whole Foods supermarket. “That makes it a dynamic and active place—everyone needs groceries,” she explained. “It is essential that we become pro-city,” Taylor said. It is not enough to be for smart growth or community development.

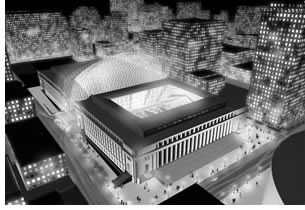

2. Infrastructure: Public investment, public realm: Investment in infrastructure is a given in Asia and Europe, Taylor explained. “Infrastructure is the skeleton around which the city can be shaped.” Just to stay current with our infrastructure needs would take an investment of billions of dollars nationally, and “there is no national policy for infrastructure.” The change also requires a shift in thinking about infrastructure. For example, SOM “replaced” the long-gone but not forgotten Penn Station in New York City by thinking of the restoration of McKim Mead and White’s Farley Building, (pictured) a historic postal facility located across Eighth Avenue from the current station, as a “great corridor of connection. It’s the belt of 33rd Street that connects two airports and Midtown,” Taylor said.

3. Commitment to community: Taylor presented as an example the Urban Land Institute’s presence in New Orleans after Katrina. The group developed a plan “Bring New Orleans Back” that includes an economic plan that offers a living wage; emphasizes infrastructure; allows for rebuilding, then reviving, and then repositioning for long-term growth; and emphasizes the rights of property owners.

Additionally, the plan calls for a strategy to protect the wetlands of coastal Louisiana, which vanished at an alarming rate in the wake of Katrina. The ULI’s plan strategy works with topography to create three levels of investment zones for the region. In the first, the least risky, development decisions lie with the individual; in the second zone, decisions must be shared among neighbors; in the third zone, public input is required for decisions.

“Without our engagement, we will not be where we need to be to bring New Orleans back,” Taylor said.

Taylor concluded with five challenges toward a new urbanism:

- Increasing density in the city core—as well as in the suburbs and territories

- Tackling the challenge of affordable housing

- Investing in essential infrastructure

- Creating an inclusive public realm

- Finding, preserving, and protecting uniqueness where it can be found.

Morrish: From “Drain” to “Harvest”

Morrish: From “Drain” to “Harvest”

Bill Morrish, the Elwood R. Quesada Professor of Architecture, Landscape Architecture, and Urban and Environmental Planning at the University of Virginia, wrapped up the session with a proposal for a paradigm shift in the way we look at the integration of architecture and infrastructure. Morrish also was the founding director of the Design Center for American Urban Landscape at the University of Minnesota’s College of Architecture and Landscape Architecture. While there, he created a nationally recognized think tank on the issues of metropolitan urban design. He carries on this work at the University of Virginia through interdisciplinary teaching and research.

Morrish quoted Cornell West: “The way we treat our infrastructure is the way we treat ourselves.” He spoke of noted architectural historian Reyner Banham’s classic Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies (Penguin, 1971), which explained how architecture is shaped and inherently tied to the city through the beach, the freeways, the flatlands, and the foothills.

Morrish quoted Cornell West: “The way we treat our infrastructure is the way we treat ourselves.” He spoke of noted architectural historian Reyner Banham’s classic Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies (Penguin, 1971), which explained how architecture is shaped and inherently tied to the city through the beach, the freeways, the flatlands, and the foothills.

Morrish explained that our fundamental relationship to architecture must change. “We must move from ‘drain’ to ‘harvest of our natural environment.’ We can catch the rain and sun instead of trying to fight them and keep them out. “This opportunity changes the paradigm and opens the opportunity of architecture,” he explained.

We need to view architecture and landscape as infrastructure, Morrish said. The infrastructure we created in the 1950s created the economy of the 1980s and 1990s, he said, and the infrastructure we create today will create future economy. Our concern with a city’s health, safety, and welfare will soon be defined as concern with a city’s quality of life. It will not be defined in terms of its current “silos,” but rather health, safety, and welfare integrated together. “Additionally, 80 to 90 percent of infrastructure is built and managed by the state and local governments. We need to decide who is going to control our infrastructure—the public or private realm,” he said.

Morrish proposed four new ecologies:

- Architecture that reveals the city’s inaugural terrain infrastructure, i.e., buildings that celebrate the soul and true nature of place; his example is the Phoenix Public Library by bruderDWL architects, a “public building as oasis” that celebrates Phoenix’s severe climate

- Architecture that enriches the overlay between the region’s economic and ecological systems—its second nature; trees in the midst of a commercial district might be an example

- Architecture that acts as a “glocal” connector in the “glocal” [global and local] arena; his example was the noted World Trade Center semi-finalist proposal by THINK, of which Morrish was part (pictured)

- Architecture that operates as a generative hub, i.e., produces more than it was expected to create; he used as an example an affordable housing project in San Ysidro by estudio teddy cruz.

Harking back to his original analogy, Morris concluded, “When architecture harvests rains, we move from being utility users to cultural generators.” He asked the architects in the audience to think of this new creative process as making a fine gumbo—it all starts with making the right roux,” he said with a grin. If you don’t start with the right roux, it burns and then “you don’t have dinner!”

Copyright 2006 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()

This session was sponsored through the generous contribution of the McGraw Hill Construction Company.

Photos by Aaron Johnson, Innov8iv Design Incorporated.

![]()