5/2006

GWWO’s new Heritage Center design to symbolize struggles, triumphs of homesteaders

On

January 1, 1863, the Homestead Act went into effect. Legend has it that

10 minutes after midnight in Brownville, Neb., Daniel Freeman filed his

claim for 160 acres of land with $18 and a promise to make improvements

and live on it. He found his piece of the American Dream in a place four

miles west of Beatrice, Neb.—a

place that is now the site of the Homestead National Monument of America.

Now, the new $4.79-million Homestead Heritage Center, by GWWO Inc./Architects,

Baltimore, helps tell the story of these early settlers and the effect

the Homestead Act had on people, the land, and the world. The visitor’s

experience begins with an entrance at the eastern edge of the site and

continues west through the building and onto the prairie to recall the

movement of westward expansion.

On

January 1, 1863, the Homestead Act went into effect. Legend has it that

10 minutes after midnight in Brownville, Neb., Daniel Freeman filed his

claim for 160 acres of land with $18 and a promise to make improvements

and live on it. He found his piece of the American Dream in a place four

miles west of Beatrice, Neb.—a

place that is now the site of the Homestead National Monument of America.

Now, the new $4.79-million Homestead Heritage Center, by GWWO Inc./Architects,

Baltimore, helps tell the story of these early settlers and the effect

the Homestead Act had on people, the land, and the world. The visitor’s

experience begins with an entrance at the eastern edge of the site and

continues west through the building and onto the prairie to recall the

movement of westward expansion.

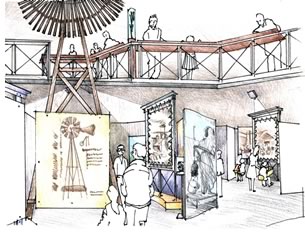

The design team, center officials, members of Nebraska’s congressional delegation, and other public leaders, broke ground on the project April 21. The new 10,600-square-foot facility will include 21 exhibit areas displaying many of the more than 52,000 artifacts in the monument’s collection, most of which have never been available to the public; a curatorial storage area; and the Homestead land-entry case files.

Keeping it simple

Keeping it simple

Perhaps the power of the story of the homesteaders, says Alan Reed, AIA,

GWWO president and design principal, comes from the simplicity of their

existence. “This experience forged symbiotic relationships involving

the interdependency of person, tools, and the land. This is what we

were thinking about as we approached the design of this project.” For

many who visit the center, the building will also be a link to their

heritage.

The architects ask visitors to make their own symbolic journey across the prairie. They divide the visitor experience into four elements:

- Transition. The land and planted fields take prominence as the site becomes shielded from view, creating a “metaphorical journey backward from modern agrarian society to the virgin prairie many homesteaders encountered.”

- Approach. Cars and buses are left behind for an approach to the site on foot. A 160-foot “living wall” runs from the parking lot to the center and includes exhibits on all 30 homesteading states. Following the wall, visitors get their first look at the new center.

- Entry. First, only the sky with a windmill silhouetted in the foreground is visible. As visitors move through the lobby, the view opens up to the prairie—the same view to the raw land that greeted homesteaders more than 140 years ago. Careful siting, Reed notes, enables the architecture to frame a view of the restored prairie of the Freeman homestead (the first claimed), emphasizing the untouched vastness that was the West.

- Exit. Visitors exit into an outdoor plaza that provides access to the Freeman homestead, the Palmer-Epard cabin and the Park’s trail system. From the vantage point of the plaza, the restored prairie is poignantly juxtaposed with the surrounding countryside.

The experience itself is also a teaching tool: The parking lot is one

acre (1/160 of an original homestead) to answer a common visitor question: “How

big is an acre?”

The experience itself is also a teaching tool: The parking lot is one

acre (1/160 of an original homestead) to answer a common visitor question: “How

big is an acre?”

Breaking sod

The distinctive, two-story building provides a visual connection to natural

and cultural resources found on the Freeman Homestead Claim. “The

building is intended to grow from the land and symbolize the struggles

and triumphs of the original homesteaders,” Reed says. An upturned

roof represents sod as it is turned by a plow.

“Just as sustainability was a way of life for the early homesteaders,

so it is for this facility,” notes the National Park Service. The

two-story compact floor plan can be efficiently conditioned by the central

mechanical space. The notion of growing from the land is as much practical

as it is symbolic. A portion of the building is constructed below grade

to provide shelter from tornados. The main glass wall and clerestory

windows welcome natural light into the lobby, where the visitor services

are located. Daylighting will also be used in other spaces to reduce

energy consumption.

“Just as sustainability was a way of life for the early homesteaders,

so it is for this facility,” notes the National Park Service. The

two-story compact floor plan can be efficiently conditioned by the central

mechanical space. The notion of growing from the land is as much practical

as it is symbolic. A portion of the building is constructed below grade

to provide shelter from tornados. The main glass wall and clerestory

windows welcome natural light into the lobby, where the visitor services

are located. Daylighting will also be used in other spaces to reduce

energy consumption.

The building is slated to be opened Sunday, May 20, 2007, the 145th anniversary of the passing of the Homestead Act.

—Tracy Ostroff

Copyright 2006 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()

Did you know . . .

Abraham Lincoln signed the Homestead Act in 1862, after the secession of southern states. It became the law of the land on January 1, 1863, turning over vast amounts of the public domain to private citizens. Ten percent of the area of the U.S.—270 millions acres—was claimed and settled under this act. It remained in effect until 1976, when the Federal Land Policy and Management Act repealed it (though a 10-year extension through 1986 was authorized in Alaska). During the 124-year history of the Homestead Act, more than 2 million people filed for 160-acre parcels of the public domain. Of these 2 million, about 783,000 (about 40 percent) were successful, fulfilling all the requirements of the government and earning the title to their property.

A homesteader had only to be the head of a household and at least 21 years old to claim a 160-acre parcel of land. Settlers from all walks of life including newly arrived immigrants, farmers without land of their own from the East, single women, and former slaves came to meet the challenge. Each homesteader had to live on the land, build a home, make improvements, and farm for five years before they were eligible to “prove up.” A total filing fee of $18 was the only money required, but sacrifice and hard work exacted a different price from the hopeful settlers. (Source: National Park Service)

![]()