5/2006

by Russell Boniface

Associate Editor

The frog wants no part of the bog. The school trailer bog, that is.

More than 200,000 common trailers are currently used as temporary classrooms by schools across the United States. Project FROG, Inc., a San Francisco-based design company, aims to vanquish “trailer blight” by offering schools a 21st century alternative. Last March, the firm unveiled its first prototype at San Francisco’s City Hall: a sleek, high-performance modular classroom. Since then, Project FROG has launched pilot modular classrooms, and in fall 2007 will have its futuristic, flexible classrooms available for national distribution for all levels of education.

Project

FROG Inc., focuses exclusively on designing, building, and deploying

high-performance modular classrooms. The acronym FROG refers to Flexible

Response to Ongoing Growth. The Project FROG leadership team draws from

MKThink, a San Francisco-based design and architecture research firm

that has done architecture research for the educational field, both K-12

and post-secondary. Project FROG is the brainchild of MKThink's founder

and principal, Mark Miller, AIA, who believes that the common trailer

classroom is ineffective, inflexible, and just an all-around “bummer.” He

believes schools with limited budgets might see Project FROG as an alternative

to trailer classrooms, and a lower-cost solution to permanent construction.

Project

FROG Inc., focuses exclusively on designing, building, and deploying

high-performance modular classrooms. The acronym FROG refers to Flexible

Response to Ongoing Growth. The Project FROG leadership team draws from

MKThink, a San Francisco-based design and architecture research firm

that has done architecture research for the educational field, both K-12

and post-secondary. Project FROG is the brainchild of MKThink's founder

and principal, Mark Miller, AIA, who believes that the common trailer

classroom is ineffective, inflexible, and just an all-around “bummer.” He

believes schools with limited budgets might see Project FROG as an alternative

to trailer classrooms, and a lower-cost solution to permanent construction.

A bog of uninspiring rectangles

Project FROG Inc. arose out of an extensive two-year research project

conducted by MKThink to evaluate how well modular trailers serve the

temporary space needs of higher education institutions. MKThink found

that at the post-secondary level modular trailers are particularly

common, with more than 3.5 million college and university students—more

than 25 percent of all students—taking classes in them last year.

Further research showed that there are a total of 220,000 trailers

at all education levels combined in the U.S. alone, with more than

a third of them located in California.

The majority of these trailers are simple, uninspiring rectangular structures not designed for learning or aesthetics. They are often characterized by inadequate lighting and glare, drab interiors, sub-optimal air quality, poor natural and artificial light, low ceilings, mold problems, and poor student-teacher sight lines. MKThink also found that although modular trailers do indeed satisfy temporary needs for additional classroom space, they often end up remaining on campus and in use for much longer, often indefinite, periods of time.

“In our work with higher education and K-12, we became very aware of the prevalence of these trailer classrooms on college and university campuses,” says Miller. “Two and a half years ago we did a research project to understand the effectiveness and problems of these trailers. We presented that work at a conference hosted by the Society of College and University Planners. After that, we got into it more and found that either the trailers were cheap, poor-performing classrooms, or expensive custom-purpose-built classrooms, which are great, but very expensive. There was no middle ground, no alternatives.”

Miller points out that millions of students are educated in “hundreds of thousands” of cheap trailers because schools can’t afford to build permanent classrooms to accommodate that many students. “The trailers are popular because there are no alternatives. Schools can’t afford to build more permanent classrooms. So the popular thing was the trailer—it filled a need. They were fast to deploy, inexpensive, and could be relocated. But the need they filled was cost and time-driven, and the result was a poor-performing classroom.”

A better solution

This was especially evident after Hurricane Katrina. “When Katrina

came, we realized this was a bigger problem than we had realized, and

the solutions were not acceptable, so we pushed last August a new design

for the marketplace. Our research found that schools are always going

to need something temporary, fast to deploy, and that will last several

years. But they needed it to be a lot less expensive than permanent construction,

be of better quality than what was out there, and be reasonably priced.”

Miller and his team of eight architects partnered with consultants in manufacturing, structural and product engineering, interior and HVAC systems, curtain wall, and lighting, as well as working with California’s state architect.

Miller is taking the same standards that he would take for a high-performance

permanent classroom building and applying that to the pre-engineered

modular classrooms. But it was important that the units cost less than

permanent construction. “The modular classrooms had to be high-performance,

sustainable, and have good site lines, great acoustics, good environmental

conditions, good natural light, good controls on the artificial light,

access to technology . . . it had to be able to do all these things,

and be quick to deploy, mobile, and use intelligent production to make

it affordable.”

Miller is taking the same standards that he would take for a high-performance

permanent classroom building and applying that to the pre-engineered

modular classrooms. But it was important that the units cost less than

permanent construction. “The modular classrooms had to be high-performance,

sustainable, and have good site lines, great acoustics, good environmental

conditions, good natural light, good controls on the artificial light,

access to technology . . . it had to be able to do all these things,

and be quick to deploy, mobile, and use intelligent production to make

it affordable.”

Classroom layouts accommodate diverse needs

The stylish, portable classroom designs by Project FROG are far removed

from the ugly rectangle trailers bogging down school campuses. Prototype

units are currently being tested in a pilot program. The single unit

is the tapered, wing-shaped “Dragonfly;” the double unit

is the wider, parallel “Turtle.” The average unit is about

1,000 square feet with exterior dimensions of 50 feet long x 30 feet

wide, but length can vary from 33 to 55 feet. The average interior

dimension is 29 feet long x 30 feet wide. Both the “Dragonfly” and “Turtle” come

in larger, wide-body models and can be joined together as two or three

units, generating up to 3,000 square feet that can serve as a lecture

hall for up to 180 students or provide space for a gymnasium. The classroom

modulars have a life expectancy of 10 years, but Project FROG believes

that with proper maintenance and care, FROG units will last as long

as traditional buildings. The units are packaged for efficient transportation

and easy on-site assembly.

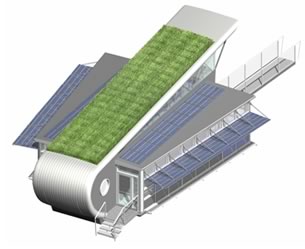

Both the Dragonfly and the Turtle are lightweight and constructed of custom-colored steel panels that can interchange with glass panels. The units have a sloping clerestory for additional transparency and natural light. The glass can add up to 800 square feet of natural light on the single-unit Dragonfly. The units have nine-foot-high tile ceilings, an exterior glass door, low-VOC carpet tiles, and a dual-layer metal roof above a sloped truss roof system. And, if a “green modular” is what you want, there are LEED™-certified units equipped with side exterior winged solar panels, with specialty roofs that can clean acid rain. The classrooms meet or exceed all requisite building codes for a permanent structure and are FEMA-compliant.

Three parts form an adaptable solution

The units’ modular system is composed of three integrated parts:

the Shed, the Sled, and the Power Pack. The Shed, which houses the actual

learning environment, is a lightweight expandable frame with a sloping

clerestory. By varying the materials in the panels, such as fiberglass,

tensile fabric, and glass, the units can be customized for different

climates and uses. The Sled is a universal platform that attaches underneath

the Shed, creating a raised floor in the classroom. The Sled distributes

heating, cooling, and ventilation. The Power Pack clips on to one end

of the FROG. Its base and rear unit accommodate the main HVAC, electrical,

telecommunications, and lighting systems, while the remainder of its

compartment can serve various specialized user functions ranging from

a restroom to a laboratory fume hood.

“The idea is that they can be adapted for any size classroom at

any education level,” says Miller. “The interior is quite

flexible to allow different types of classrooms to exist. For example,

you can reconfigure a basic unit’s interior to transform into tiered

seating for a lecture hall, science laboratory, choir room, art or music

studio, administrative office, or seminar room. There are many options.

You can even combine units. And the mechanical distribution system can

be transformed to accommodate any grade level. It can fit both the needs

of a kindergarten classroom or be adapted with additional technology,

piping, and plumbing for something as advanced as a university laboratory.”

“The idea is that they can be adapted for any size classroom at

any education level,” says Miller. “The interior is quite

flexible to allow different types of classrooms to exist. For example,

you can reconfigure a basic unit’s interior to transform into tiered

seating for a lecture hall, science laboratory, choir room, art or music

studio, administrative office, or seminar room. There are many options.

You can even combine units. And the mechanical distribution system can

be transformed to accommodate any grade level. It can fit both the needs

of a kindergarten classroom or be adapted with additional technology,

piping, and plumbing for something as advanced as a university laboratory.”

And they don’t all look alike. “You can play with color, patterns, and facades . . . more glass or less glass for more transparency or less transparency,” explains Miller. “We made them aesthetically appealing to the point of being friendly and accessible. We learned that this was especially important in the pre-K through 12 grades. One of the problems about the common trailers was that they were ugly and they were a real bummer. Kids were, in effect, being told, ‘I’m sorry we don’t have money and I’m sorry we don’t have room, so you are going into the trailers.’ The aesthetics to our modular classrooms had to be modern, colorful, future-thinking, and have characteristics that would attract kids. We matured the design in accord with that.”

Pilot program a jumping-off point

Project FROG and MKThink are currently looking for one or two more schools

to participate in its pilot program, and getting additional financing

from investors for its project development. The manufacturing time

for a Project FROG classroom is currently four months. This fall and

winter, it will finalize testing on the modular classrooms and prepare

for a wide, commercial distribution for fall 2007, with the intent

of reducing manufacturing time of the units to 60 days. The basic FROG

unit will cost $150–$200 per square foot depending on features and

customization (below permanent construction costs), making the total

cost between $150,000 and $200,000, depending on features. Although

Project FROG is looking before it leaps, it sounds like the program

is confidently ribbiting up the right tree.

“We are getting great feedback so far from schools,” enthuses Miller. “This isn’t something we developed in six weeks for a design competition . . . we have been working on it for almost three years, going from research to making it real. Here is something that is high performance, stylish, getting engineered, and becoming available commercially for schools up and down the academic spectrum.”

And hopping clear away from the bog.

Copyright 2006 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()

A Frog in the Bog, written by Karma Wilson and illustrated by Joan Rankin (2003, Margaret K. McElderry Books) is a picture book for young children.

![]()