5/2006

by Norman Rosenfeld, FAIA

excerpted from Professional Practice 101, 2nd edition

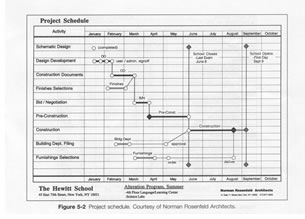

To keep projects on-time and on-budget, our firm develops a project schedule. We compare the documentation time-period (whether it’s schematic, design development, or construction documents) with the fee. We perform various iterations of fees and projections of time.

In a task-budget spread sheet, we show all the tasks in the project—by phase—to which we attribute time (each staff person assigned to the project is represented by one column in the matrix and his or her hours get filled in for each task listed). We use the total time multiplied by an assumed average rate per hour, which results in the gross cost. For our example project, the client finally gave us the go-ahead in January; we knew the project had to begin construction in June, so we used the time frames from the schedule and then assigned hours to the various tasks that needed to be accomplished.

Our fee is always based on time since that is what we feel we are selling

as professionals—our time. The rate varies, depending on the market

and the ultimate fee a client expects to pay for a particular project,

since clients have conventionally thought of fee as a percentage of construction

cost. We have a long history of doing certain projects and know the total

effort that they will require, so although we will not necessarily relate

our fee to a percentage of construction cost, it is a valid second check.

For example, a 10,000-square-foot renovation for a high-tech environment

will require x number of hours in programming, y number of hours in schematic

design, z number of hours in construction documents, and so on. We then

project that to arrive at a number at the end. Then we cross-check it

against the anticipated construction cost of the project to determine

the percentage fee. It’s not a science; it’s an art with

a little bit of science mixed into it.

Our fee is always based on time since that is what we feel we are selling

as professionals—our time. The rate varies, depending on the market

and the ultimate fee a client expects to pay for a particular project,

since clients have conventionally thought of fee as a percentage of construction

cost. We have a long history of doing certain projects and know the total

effort that they will require, so although we will not necessarily relate

our fee to a percentage of construction cost, it is a valid second check.

For example, a 10,000-square-foot renovation for a high-tech environment

will require x number of hours in programming, y number of hours in schematic

design, z number of hours in construction documents, and so on. We then

project that to arrive at a number at the end. Then we cross-check it

against the anticipated construction cost of the project to determine

the percentage fee. It’s not a science; it’s an art with

a little bit of science mixed into it.

With our example project, much hand-holding to develop the project was required, and it was speculative as to whether the fee level we set would generate a profit. When the project is complete and we find that we’re in a slight loss position, that may be a result of overhead—the cost of running the office. The number of people and projects in the office and the amount of total fees affect the proportion of fee that may be attributable to overhead. The office expenses are fixed, and if there is more work and more projects, then the overhead decreases and it costs less to do a job. Things are slower now than we’d like them to be, so this job is bearing a high burden of overhead. As a practice, we do not pass that higher overhead to individual clients, since they are not responsible for the high overhead at that particular point. We analyze fees and profitability at the end of a year on an annualized basis to see how many projects we had and how the overhead is allocated. It is possible to take a capsule view of a particular project, but we believe its real profitability will shake itself out at the end of the year.

One other thing we try to avoid is committing to lump-sum fees for things over which we have no control. For example, for some projects, we will not establish a fee until we’ve done a study, which then provides us with an understanding of the scope and complexities of the project, its budget, and how it is to work with that client. All clients have their own vagaries, and certain clients are more costly for the architect to work with. For instance, they may be indecisive, they can never arrange or attend meetings on time, they will hold decisions for weeks and not respond because they can’t get consensus from their organization, and they will frequently change their minds—you learn that very quickly when you do a preliminary study for them.

The other end of the project is during construction, where we will establish a lump sum to do construction observation. If the contractor turns out to be a poor performer, however, who slows it all down and costs the architect more field visits, we may seek an increase in our fee for these additional services.

A carefully established and monitored time budget will let you know

as the project unfolds how you’re spending time and fee. This helps

to ensure that you don’t fall into a hole too fast, and it lets

you discover problems earlier rather than later. Some problems can’t

be corrected because some projects will have certain built-in problems

that could not have been anticipated. Such a project becomes a sinkhole.

Sometimes you have a client who is very difficult and indecisive, and

you have to suffer. But, on balance, we have run a profitable practice;

some projects have been very profitable, some less so.

A carefully established and monitored time budget will let you know

as the project unfolds how you’re spending time and fee. This helps

to ensure that you don’t fall into a hole too fast, and it lets

you discover problems earlier rather than later. Some problems can’t

be corrected because some projects will have certain built-in problems

that could not have been anticipated. Such a project becomes a sinkhole.

Sometimes you have a client who is very difficult and indecisive, and

you have to suffer. But, on balance, we have run a profitable practice;

some projects have been very profitable, some less so.

Profit, of course, is very important so that you can be in practice (business) to do the next project and can invest some of that profit in new computers and software, for example, to stay current with technology. Some of the profit goes to marketing—developing printed materials, photography, and so on. How to spend your profits is a necessary business judgment. A lot of those profits go to bonuses to staff at the end of the year; good staff is the most important resource of any office. We believe this and put it to action. For example, we think it is an important responsibility to recognize our staff’s contributions with bonuses and salary increases.

Monitoring projects

People fill out time cards on a daily basis. The time card, for all firm

members, including principals, is perhaps the most significant tool

for establishing and tracking the cost to produce projects. The time

cards are recorded by our bookkeeper biweekly (corresponding to our

pay periods). That time goes into a computer, and job cost reports

are developed that indicate how much time has been spent (and by whom)

on the project. If you see that you are exceeding the budget, you will

do one of three things: You will nod your head and keep going, you

will determine what you should be doing in the next period to correct

the over-expenditure of the previous period (and see where you went

wrong), or you may attribute some particular project- or client-specific

reason to it—and perhaps seek an additional fee from the client.

You may determine that the additional fee might be appropriate but

that it is politically not correct to ask for it at that juncture.

After the architect’s economics at the end of the project are

known, you may then seek a fee adjustment, since you can demonstrate

to the client the real costs incurred for the work done on the client’s

behalf. Often, you will do nothing but run scared to the next phases

of the project and let people in the office know that they should try

to be more efficient and effective in coming out at the end.

The project architect (or manager) monitors what people are doing—monitors the progress being made against the budget that has been created. I’d like to add that, in our office, design quality is never compromised. That is a problem because we provide our services, and so represent to our clients, that we can only turn the faucet on full. Because of our reputation (the client’s selection of us has usually been based on the quality of our past work or on what others have said about us), there’s no way that we can’t do what we had represented or what the client expected from us. It is an enormously competitive environment, and there are other firms that are getting projects because they are quoting lower fees than we are. We are letting these projects go because we simply can’t perform at that lower fee level without compromising quality along with our reputation. This is a very big dilemma these days.

Copyright 2006 Andrew Pressman. Published by John Wiley & Sons,

Inc., Hoboken, N.J.

Excerpted with permission.

Copyright 2006 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()

Norman Rosenfeld is the founding principal of Norman Rosenfeld Architects, based in New York City, which specializes in health-care, education, and commercial projects.

Helping fill the oft-lamented gap between design education and practice, Professional Practice 101: Business Strategies and Case Studies in Architecture, 2nd ed., by Andrew Pressman, FAIA, offers easy-to-read comprehensive coverage of creating an architecture practice, guiding it through the competitive and regulatory shoals, making it thrive, and serving the public good. “Think of this book as helping you give your practice a shape and form, as you do your buildings,” advises Thomas Fisher. “Just as we would never assume that there exists one building form or organization plan that fits all needs, so too should we never assume that there exists one form of practice or way of organizing an office or delivery process.”

For more information on the book, call the AIA Store, 800-242-3837, option 4.

![]()