5/2006

by James B. Atkins, FAIA, and Grant A. Simpson, FAIA

Any architect who has experienced the construction phase of services will likely agree that contractor submittals are a daunting and risky part of our work. They tend to be numerous, complex, and time-driven. Their success in efficiently traversing the review process is largely dependent on the submitting contractor’s scheduling, sequencing, checking, and coordination.

Meanwhile, the contractors are struggling with the prerequisites of subcontractor and vendor selection and product buy-out along with the contracts and purchase orders that follow; all the while trying to comply with the schedules that they submitted at the start of construction.

The architect is often pressured in contract negotiation to reduce the number of submittal review days with the assumption that it will in some way accelerate the project. The reality is that the steps in the process are usually the same no matter what, and if acceleration is desired, effective coordination, timely actions, and established procedures subscribed to by all players will be of greater benefit than hurried actions and eliminated steps.

This article will address the activities that make up the submittal process along with the complexities and challenges contained therein. It will review the components and activities associated with submittals along with suggestions for establishing and administering an efficient and effective review process.

Finally, it will offer actions you can take to manage your risks in this area of services. Issues such as how to manage multiple discipline reviewers, what to do when the submittal schedule is late or not provided, how to deal with forced substitutions that are more and more common in submittals, and what actions to take with submittals that are poorly prepared or inadequately reviewed by the contractor will be addressed.

Finally, it will offer actions you can take to manage your risks in this area of services. Issues such as how to manage multiple discipline reviewers, what to do when the submittal schedule is late or not provided, how to deal with forced substitutions that are more and more common in submittals, and what actions to take with submittals that are poorly prepared or inadequately reviewed by the contractor will be addressed.

Project success is dependent on the checks and balances inherent in submittal process, and for it to run smoothly and efficiently, there should be a set of rules and procedures. Like Edmund Hoyle, when he set out the rules for the game of whist in England in 1743, and forever coined the phrase, “According to Hoyle,” if a set of rules and procedures is established for submittals, and it is managed accordingly, the chances of reducing risk and achieving success can be greatly improved.

Responsibility for submittals

The purpose and use of submittals in the design and construction process are not always well understood. To understand fully what submittals are and what they do, we should first review the basics.

Who Prepares Submittals? Submittals are prepared or furnished by the contractor. The architect does not prepare, seal, or issue submittals, and it is not responsible for their accuracy or completeness. AIA Document A201™-1997, General Conditions of the Contract for Construction, (A201) states:

3.12.1: “Shop drawings are drawings, diagrams, schedules and other data specially prepared for the Work by the Contractor, or a Subcontractor, Sub-subcontractor, manufacturer, supplier or distributor to illustrate some portion of the Work.”

The Purpose of Submittals. The purpose of submittals such as shop drawings and the conceptual nature of construction documents prepared by design professionals are addressed in A201:

3.12.4: “The purpose of their submittal is to demonstrate for those portions of the Work for which submittals are required . . . the way by which the Contractor proposes to conform to the information given and the design concept expressed in the Contract Documents.” (bold added)

Submittals are not contract documents. The contractor prepares submittals, and the architect prepares contract documents. A201 states:

3.12.4: “Shop Drawings, Product Data, Samples and similar submittals are not Contract Documents.”

The

Contractor Reviews and Approves Submittals. Submittals represent that the contractor has selected and coordinated appropriate products, has reviewed the submittals, and has determined and confirmed the finite details and dimensions required to complete the work. From A201:

The

Contractor Reviews and Approves Submittals. Submittals represent that the contractor has selected and coordinated appropriate products, has reviewed the submittals, and has determined and confirmed the finite details and dimensions required to complete the work. From A201:

3.12.6: “By approving and submitting . . . submittals, the Contractor represents that the Contractor has determined and verified materials, field measurements and field construction criteria related thereto, or will do so, and has checked and coordinated the information within such submittals with the requirements of the Work and of the Contract Documents.”

This common language describes routine procedure throughout the industry. The purpose for the contractor’s check is to coordinate and verify that the work, as the contractor has divided it among the trades, will comply with the requirements of the contract documents.

Submittals are required to do the work. Submittals are the confirmation of the contractor’s intent to comply with the design concept. The importance of this compliance process is emphasized by the prerequisite condition stated in A201:

3.12.7: “ The Contractor shall perform no portion of the Work for which the Contract Documents require submittal and review of Shop Drawings, Product Data, Samples or similar submittals until the respective submittal has been approved by the Architect.”

Submittals are not intended to be an opportunity to alter the design concept by either the designer or the contractor. Their purpose is to express how the finished building will be constructed. The contractor reviews submittals to determine if they represent the work as they have purchased and will place it. The architect does not review submittals to determine if the finite details and dimensions are correct because only the contractor has control of or responsibility for the work, the required dimensions, and how all the pieces fit together to form the completed project.

The Architect’s Role

The Architect’s Role

The architect’s role in reviewing submittals is addressed in A201 as follows:

4.2.7: “The Architect will review and approve or take other appropriate action upon the Contractor’s submittals . . . but only for the limited purpose of checking for conformance with information given and the design concept expressed in the Contract Documents . . . ”

Although the architect’s limited review is clearly stated, section 4.2.7 continues to clarify what the review is not intended to accomplish.

4.2.7: “ . . . Review of such submittals is not conducted for the purpose of determining the accuracy and completeness of other details such as dimensions and quantities . . . all of which remain the responsibility of the Contractor . . . ”

The limitations of the architect’s review as stated in the general conditions are straightforward. However, for many years some owners and contractors have alleged the architect’s review serves as “the architect’s guarantee” that the submittal is precisely correct, coordinated with other submittals, and includes everything required to complete the project. Afterwards, should the submittal prove to be incomplete, incorrect, or result in missing or nonconforming work, they allege that it is the architect’s fault that the contractor did not fulfill its contractual responsibility to prepare the submittal appropriately. Such allegations fail to acknowledge the contractor’s sole responsibility for the work as addressed in A201:

3.12.8: “The Work shall be in accordance with approved submittals except that the Contractor shall not be relieved of responsibility for deviations from requirements of the Contract Documents by the Architect's approval of Shop Drawings, Product Data, Samples or similar submittals . . . ” (bold added)

This alleged responsibility of the architect for failing to “catch” the contractor’s errors flies in the face of AIA general conditions. This mistaken perception will be explored in detail in an upcoming article entitled, “Absolute Power or Absolution?” scheduled for publication later this year.

Types of submittals

Types of submittals

There are numerous types of submittals, including shop drawings, product data, and samples as defined in A201:

3.12.1: “Shop Drawings are drawings, diagrams, schedules and other data specially prepared for the Work by the Contractor…”

3.12.2: “Product Data are illustrations, standard schedules, performance charts, instructions, brochures, diagrams and other information furnished by the Contractor…”

3.12.3: “Samples are physical examples which illustrate materials, equipment or workmanship and establish standards by which the Work will be judged.”

Items and information that fall within these categories can include, but are not limited to:

- Physical mock-ups

- Product, material, or system performance calculations

- Physical product and finish samples

- Coordination drawings

- Key schedules

- Warranties and guarantees

- Record drawings

- Operations manuals.

Submittal requirements

Submittals are an integral part of the contractor’s obligation to schedule and coordinate the work and illustrate to the architect that their finished project will be in accordance with the requirements of the contract documents. A201 states:

3.12.5: “The Contractor shall review for compliance with the Contract Documents, approve and submit to the Architect Shop Drawings, Product Data, Samples and similar submittals required by the Contract Documents with reasonable promptness and in such sequence as to cause no delay in the Work … Submittals which are not marked as reviewed for compliance with the Contract Documents and approved by the Contractor may be returned by the Architect without action.”

Similar language is included in AIA Document, A107™-1997, Abbreviated Standard Form of Agreement Between Owner and Contractor for Construction Projects of Limited Scope, and AIA Document, A141™-2004, Standard Form of Agreement Between Owner and Design-Builder.

MASTERSPEC

Project specifications customarily address submittals and the submittal review process. For example, MASTERSPEC® division

1330 tracks A201 and offers specifics for submittal procedures, including

time for review, the number of copies of submittals, contractor’s review stamp wording, and transmittal and tracking documents. For review purposes, MASTERSPEC identifies submittals in two categories: action submittals, which require the architect’s responsive action, and informational submittals, which do not require the architect’s approval.

Submittal routing

Submittal routing

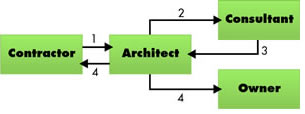

Submittal

Review Flow Diagram

COURTESY HKS ARCHITECTS

As indicated in the flow chart above, the contractor submits to the architect (1), who routes appropriate submittals through consultants (2), who returns the reviewed copy to the architect (3), who checks for architectural issues and returns copies to the contractor and owner (4).

The submittal game

To manage submittals effectively,

it is important that the steps in the submittal process be clearly defined

to all participants. The following sequence describes the activities

and actions that may be used for processing submittals. Project requirements

vary, and these steps may not apply to all projects.

Subcontractor/supplier prepares submittal. The contractor, subcontractors, and product vendors are usually most informed about the specified product or system. They should prepare, in collaboration with the manufacturer, the detailed drawings that describe precisely how their product will be coordinated with adjacent building products and systems and incorporated into the work. A wise subcontractor will have the manufacturer confirm in writing that the application of the product or system is appropriate.

Unfortunately, perhaps in response to the potential for litigation and the pressures of risk management, there is often a propensity to indicate surrounding materials vaguely and designated as “by others.” Although this may provide a vendor or subcontractor with plausible deniability as to the requirements of coordination with surrounding systems, it provides the contractor with little opportunity for effective coordination of the trades. Submittals that do not adequately address the specifics for installation into the project should be rejected by both the contractor and the architect.

Unfortunately, perhaps in response to the potential for litigation and the pressures of risk management, there is often a propensity to indicate surrounding materials vaguely and designated as “by others.” Although this may provide a vendor or subcontractor with plausible deniability as to the requirements of coordination with surrounding systems, it provides the contractor with little opportunity for effective coordination of the trades. Submittals that do not adequately address the specifics for installation into the project should be rejected by both the contractor and the architect.

Subcontractor and/or supplier submits to general contractor. The subcontractor, after a careful review of the submittal, submits the information to the general contractor, with an attached transmittal, in accordance with the accepted submittal schedule.

General contractor affixes control number. The general contractor stamps the submittal “received” and affixes a permanent control number in accordance with the project specifications. The submittal is logged into the approved tracking system.

Contractor reviews and marks-up submittal. The general contractor performs a detailed review of the submittal, coordinating it with adjacent materials and systems, and marks up the submittal to indicate dimensional corrections and specific detail configurations. If the contractor finds the submittal to be inadequately prepared, the contractor should return the submittal to the subcontractor for revision or correction. The submittal should be forwarded to the architect only after it thoroughly and accurately represents how the contractor intends to comply with the contract documents. The contractor remains responsible for compliance with the contract documents without regard of the architect’s interaction with the submittals.

Contractor stamps submittal approved. When the marked-up submittal is found to be acceptable, the contractor affixes a review stamp with a signature and date.

Contractor submits to architect. Only after the contractor’s approval is the submittal sent to the architect with an attached transmittal. The action is logged into the approved tracking system.

Architect receives submittal and distributes. The architect stamps the submittal “received” and logs it into the submittal log. If the submittal requires review by a consultant, the submittal is routed to the consultant with an attached transmittal.

Architect receives submittal and distributes. The architect stamps the submittal “received” and logs it into the submittal log. If the submittal requires review by a consultant, the submittal is routed to the consultant with an attached transmittal.

Architect reviews and marks-up submittal. The architect reviews the submittal, but with the limitation stated in A201.

4.2.7: “ . . . only for the limited purpose of checking for conformance with information given and the design concept expressed in the Contract Documents,”

The Architect marks up the submittal if deemed necessary. If the submittal has been reviewed by a consultant, the architect reviews it for impact on the architectural scope and marks it up accordingly, noting that its review is for architectural scope only.

Architect stamps submittal. The architect affixes the review stamp, indicating the action taken. Options can include: approved, approved as noted, revise and resubmit, no action taken, or submittal not required by contract documents.

Architect returns submittal to contractor. The architect returns the submittal to the contractor with an attached transmittal, logging submittal description, submittal date, and actions taken.

Contractor coordinates submittal with work plan and other trades. The contractor stamps the submittal received and reviews the marked-up submittal, coordinating it with other submittals, adjacent work and the contractor’s Work Plan. The issue of the contractor’s Work Plan is discussed in the September 2005 article Drawing the Line.

Contractor returns submittal to subcontractor. The contractor returns the submittal, with attached transmittal, to the subcontractor to allow fabrication or installation as appropriate.

Contractor returns submittal to subcontractor. The contractor returns the submittal, with attached transmittal, to the subcontractor to allow fabrication or installation as appropriate.

This process involves a lot of stamping. After all the received stamps and review stamps have been affixed, the document can get quite cluttered. This image depicts what a submittal could resemble after traversing the review process.

PHOTO BY JIM ATKINS AND GRANT SIMPSON

Submittal review recommendations

Some steps to take that could improve your experiences with the submittal process are:

- Allow adequate review time in the owner-architect agreement and specifications

- Require a valid submittal schedule from the contractor so you can plan your commitments

- Review the submittal process in the pre-construction conference

- Use a unique control number on each submittal

- Log and track each submittal

- Have multiple reviewers use different color markers for tracking

- Do not review submittals not required by the contract documents.

The key to implementing and managing submittals is to address the issue up front in your contracts and specifications and thoroughly review the process in the pre-construction conference. You should bring your general conditions and specifications to the pre-construction conference and each job meeting and discuss openly the requirements for submittal scheduling, contractor review, submission, and processing.

Tough cards to play

Regardless of how well a submittal process is planned, issues can arise that challenge efforts and test resolve. Since the same issues are prone to arise on any project, actions can be taken to help reduce the challenges or possibly prevent them from occurring altogether.

The following challenges may be encountered by the architect on a project during the submittal process.

Inadequate submittal time in contract. The architect has agreed to an abbreviated submittal review time in the owner-architect agreement. This often results in confrontational tracking of “aged” submittals by the contractor. These aged submittals are often cited by the owner and contractor when they allege delays caused by the “poor performance” of the architect.

Possible solution. The best way to allow sufficient time for submittal review is to insist on an adequate duration during contract negotiation. A popular period is a minimum of 10 business days on average. The average time will allow you to bank review time from quickly reviewed submittals to use on those that take longer. This may require an explanation to the owner as to why this average duration is needed, so be ready to make your case. Many contract negotiation issues can be resolved with adequate client enlightenment.

Possible solution. The best way to allow sufficient time for submittal review is to insist on an adequate duration during contract negotiation. A popular period is a minimum of 10 business days on average. The average time will allow you to bank review time from quickly reviewed submittals to use on those that take longer. This may require an explanation to the owner as to why this average duration is needed, so be ready to make your case. Many contract negotiation issues can be resolved with adequate client enlightenment.

No submittal schedule. The absence of a submittal schedule usually indicates that the contractor has not planned and scheduled the sequence of submittals. This often represents a serious flaw in the contractor’s work plan. A201 section 3.10.2 and MASTERSPEC sections 1320 and 1330 require that the schedule be prepared and submitted to the architect. The submittal schedule is required to be coordinated with the overall project construction schedule.

Possible solution. If the contractor refuses to provide a submittal schedule, it is advisable to document the event by sending correspondence to the owner noting the issue and advising that all previously agreed-upon review times are suspended until an acceptable submittal schedule is provided. Remember that you have a right to determine if the submittal schedule is acceptable to your administrative schedule. To provide an incentive to the contractor to provide the schedule, you may elect to send AIA document, G716™ Request for Information, requesting that the contractor provide the schedule. You may wish to track the RFI in a log to document the delay caused by the contractor’s failure to submit, as well as insist that the tardy schedule be tracked in the contractor’s submittal log.

Late submittals. When submittals do not conform to the submittal schedule, it is usually an indication that the schedule is inaccurate or the contractor is behind in project buy-out. This sometimes results in pressure applied to the architect to accelerate reviews to make up for the contractor’s poor planning.

Possible solution. If the contractor is not adhering to the submittal schedule, it is advisable to notify the contractor that they are not in compliance with the requirements of the contract documents. Make an effort to assist them in correcting the problem, but if it persists, you should advise the owner in writing that, until the contractor adheres to the accepted submittal schedule, you cannot comply with your previously agreed-upon review time, and additional costs may be incurred as a result. It is also another opportunity to send and track an RFI requesting the information.

Forced substitutions in submittals. A tactic sometimes used by the contractor to force a substitution involves waiting until a submittal is due or past due and the construction schedule is being threatened. A substituted product or system is proposed with the premise that there is insufficient time to prepare and submit the specified item, alleging that the project will be delayed unless the substitution is accepted. Owners and architects are often forced to acquiesce to the substitution because of these time constraints.

Forced substitutions in submittals. A tactic sometimes used by the contractor to force a substitution involves waiting until a submittal is due or past due and the construction schedule is being threatened. A substituted product or system is proposed with the premise that there is insufficient time to prepare and submit the specified item, alleging that the project will be delayed unless the substitution is accepted. Owners and architects are often forced to acquiesce to the substitution because of these time constraints.

Possible solution. Should the contractor attempt to wait until the last minute and submit a substituted product or system in the form of shop drawings, it is recommended that the submittal be rejected as nonconforming work and the contractor be reminded of the substitution requirements in the specifications. MASTERSPEC requires that substitutions be requested within a specified time after the notice to proceed. If the owner elects to accept the substitution, unless you feel that it is equal to or better than the originally specified product or system, you should advise the owner that it will be considered owner-approved nonconforming work and will likely be listed as an exception in the certificate of substantial completion.

The issue of forced substitutions in submittals was addressed in The Architect’s Handbook of Professional Practice, 2004 Update, in an article entitled, “Maintaining Design Quality.” The article will be included in The Architect’s Handbook of Professional Practice, 14th Ed., scheduled for publication in 2008.

Work performed without an approved submittal. Some contractors elect to put the work in place before the submittal has been approved, possibly to accelerate the work, or because there was no submittal or the contractor neglected to resubmit a previously rejected submittal. Regardless of the cause, placing work without an approved submittal is strictly prohibited by A201:

3.12.7: “The Contractor shall perform no portion of the Work for which the Contract Documents require submittal and review of Shop Drawings, Product Data, Samples or similar submittals until the respective submittal has been approved by the Architect.”

Possible Solution. If the contractor refuses to resubmit a submittal that has been noted for this action, you may wish to remind the contractor in writing of the requirements of A201, section 3.12.7, which prohibits the contractor from performing work without a required submittal. You may choose to copy the owner on the notice. This is also an appropriate opportunity to submit an RFI to the contractor requesting resubmittal.

Possible Solution. If the contractor refuses to resubmit a submittal that has been noted for this action, you may wish to remind the contractor in writing of the requirements of A201, section 3.12.7, which prohibits the contractor from performing work without a required submittal. You may choose to copy the owner on the notice. This is also an appropriate opportunity to submit an RFI to the contractor requesting resubmittal.

When claims are levied against architects, it is often argued that the architect has a responsibility to be aware of and prevent the contractor from installing work without approved shop drawings. A201, section 3.12.7, and the fact that submittals are part of the “Work” make it clear that the contractor is solely responsible for work performed in the absence of approved submittals.

Submittals are a part of the work

The contractor is paid to produce shop drawings and submittals because they are a part of the Work as defined in A201:

1.1.3: “The term "Work" means the construction and services required by the Contract Documents, . . . and includes all other labor, materials, equipment and services provided or to be provided by the Contractor to fulfill the Contractor's obligations . . . ”

As a part of the Work, we believe they come under the terms of the contractor’s warranty as reflected in A201:

3.5.1: “The Contractor warrants to the Owner and Architect that . . . the Work will be free from defects not inherent in the quality required or permitted, and that the Work will conform to the requirements of the Contract Documents.”

Many contractors diligently administer the submittal process, and when they do there are usually few problems that result. However, it is advisable to decide your alternative courses of action and be prepared to respond to challenging submittal issues should they arise.

Blind nello

The contractor’s responsibilities for submittals notwithstanding,

the architect should diligently manage its portion of the submittal review

process. The architect is expected to review the submittals in the context

of the requirements of the contract documents and review them so as to

cause no unreasonable delay in the work. An architect could fail to meet

these responsibilities if he or she started redesigning the project or

changing the scope of the work through review redlines and comments

made on the submittals.

The architect could also incur risk if he or she marks through the contractor’s submittal information and provides alternate information that is inaccurate. For example, a contractor provides a window submittal with exact dimensional information given; the architect, believing the dimensions are inaccurate, marks through the contractor’s dimensions and provides alternate dimensions. As the work is installed, it becomes apparent that the architect’s dimensions are incorrect. In this instance, the architect could be held responsible for the architect’s erroneous dimension markups. A better form of communication in this instance would be to provide a notation requesting the contractor to confirm the dimensions shown on the submittal.

Calling the hand

Calling the hand

Over 250 years ago, Edmund Hoyle evaluated the game of whist and set out rules and procedures for players to follow. His rules of games have prevailed over time to the extent that his authority is now communicated through a catch-phrase that is applied to all activities that benefit from a set of rules. The submittal process is dependent on following the rules, and success is best achieved, especially in the submittal process, when it is followed according to Hoyle.

The checks and balances inherent in the submittal process contemplated by A201 are designed to promote successful projects. Submittals are the most explicit indication of how the contractor has interpreted the design concept expressed in the contract documents. They indicate the extent to which the contractor has organized, coordinated, and developed their work plan. The speed and efficiency with which the architect can review and approve submittals is to a great extent dependent on how well the project team prepares and performs.

The best approach is to plan well and plan early. The pre-construction conference provides an opportunity to discuss how the submittal process will flow. Discussions should include document media, number of copies, review mark colors, control number format, and routing. One firm produces a project procedures manual, which includes a flow diagram for submittals. If all aspects of the process are agreed upon in advance, the chance of misunderstandings and poor participation are lessened.

As the architect, you should consider tracking submittal progress with your own log rather than relying only on the contractor’s tracking. Most contracts these days have a designated review time, and the process should be managed to stay on schedule. An effective logging system can track the contractor’s actions as well as your own. It seems that more and more project meetings these days include an adversarial and confrontational display of the architect’s shortcomings through illustrations from the contractor’s submittal log. The contractor’s shortcomings of inadequate reviews and late or missing submittals are not generally tracked in the contractor’s tracking logs. Efficient and proactive submittal management is necessary to stay on top of the game.

As we move toward more integrated project deliveries, the submittal process may change, but it will never go away. Architects will continue to produce conceptual documents, and contractors will interpret the concept through submittals. The process will likely continue to be the most critical time-driven activity in the construction process.

As we move toward more integrated project deliveries, the submittal process may change, but it will never go away. Architects will continue to produce conceptual documents, and contractors will interpret the concept through submittals. The process will likely continue to be the most critical time-driven activity in the construction process.

Set down that cup of coffee and unroll that submittal on your desk. Check to see that the contractor has affixed and signed their approved stamp, and look to see that the control number is correct. And, as you reach for your received stamp, don’t forget to be careful out there.

Copyright 2006 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()

This series will continue next month in AIArchitect when the subject will be “Visible Means: Site visits and construction observation.” If you would like to ask Jim and Grant a risk- or project-management question or request them to address a particular topic, contact them through AIArchitect.

James B. Atkins, FAIA, is a principal with HKS Architects. He serves on the AIA Documents Committee and is the 2006 Chair of the AIA Risk Management Committee.

Grant A. Simpson, FAIA, manages project delivery for RTKL Associates. He is the 2006 Chair of the AIA Practice Management Advisory Group.

This article represents the opinions of the authors and not necessarily that of The American Institute of Architects. It is intended for general information purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. The reader should consult with legal counsel to determine how laws, suggestions, and illustrations apply to specific situations.

![]()