4/2006

Nature Is the Model for Design

by Russell Boniface

Sim Van der Ryn, AIA, president of California-based Van der Ryn Architects

has been a leader in sustainable architecture for more than 35 years.

In his new book, Design for Life–part memoir, part design treatise–he

explores how architecture can better connect buildings to nature and

culture.

Sim Van der Ryn, AIA, president of California-based Van der Ryn Architects

has been a leader in sustainable architecture for more than 35 years.

In his new book, Design for Life–part memoir, part design treatise–he

explores how architecture can better connect buildings to nature and

culture.

Awarded the AIA Nathaniel Owings Award in 1996 and the California Council AIA Award in 1981, Van der Ryn approaches buildings as organisms and cities as complex ecosystems.

A lifelong passion

Thinking green is something Van der Ryn has done all his life. Design

for Life takes readers back to the architect’s native Netherlands

during World War II, then on to New York City, where Van der Ryn’s

family subsequently settled. He found refuge in nearby deserted marshes,

beaches, and vacant lots, thus starting his lifelong study of nature.

With his degree from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and licenses

in California and New Mexico, Van der Ryn pioneered sustainable architecture

in the 1960s working with then-cutting-edge, now-ubiquitous concepts

such as solar roof panels and rainwater catchment systems.

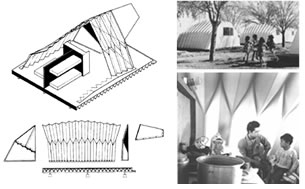

Van der Ryn became known at first for his 12-sided tent-like structures

that fold like accordions, a design that offered temporary housing for

migrant farm workers in California. His association with the back-to-nature

movement of that time included working with students, as a young professor

at the University of California, Berkeley, to build a freestanding energy

pavilion that resembled a lifeguard station. From that period he received

the label “a hippie with hubris,” which is arguably better

than the nickname that followed—Captain Compost—for his relentless

advocacy of compost toilets.

Van der Ryn became known at first for his 12-sided tent-like structures

that fold like accordions, a design that offered temporary housing for

migrant farm workers in California. His association with the back-to-nature

movement of that time included working with students, as a young professor

at the University of California, Berkeley, to build a freestanding energy

pavilion that resembled a lifeguard station. From that period he received

the label “a hippie with hubris,” which is arguably better

than the nickname that followed—Captain Compost—for his relentless

advocacy of compost toilets.

Van der Ryn founded the Farallones Institute in Occidental, Calif., in the 1970s for students to study sustainable design, organic agriculture, land restoration, and ecological waste systems. The work started by the Farallones Institute continues at the nonprofit Ecological Design Institute in Sausalito, Calif., which offers education and research services in ecological design to businesses, government agencies, professional organizations, and educational institutions.

Appointed California State Architect by Governor Jerry Brown in 1975, Van der Ryn developed the nation“s first government-initiated energy-efficient office building program. That, in turn, resulted in the first major facility in the U.S. designed to save energy, the Bateson Building, in 1979. The state architect appointment had Van der Ryn overseeing the design of all state facilities, including the design and management of the state park system. All told, his ecological designs span single-family and multi-family housing, community facilities, retreats, resort and health centers, schools, office buildings, commercial buildings, and planned communities.

His

more recent work includes the 22,000-square-foot Kirsch Center for Environmental

Studies at De Anza College in Cupertino, Calif., completed last fall

and operated by students. Designed as a teaching tool, the center features

a transparent “truth wall” that lets them study

those working parts of the building usually hidden by finishes. Among

his other outstanding designs is the Real Goods Solar Living Center in

Hopland, Calif., a 5,000-square-foot sustainability compound, completed

in 1996, on what was once a 12-acre barren site. The structures are straw

bale with curved roofs and incorporate passive solar heating and cooling,

photovoltaic and wind electricity generation, and an outdoor oasis cooled

by evaporation. Next came Van der Ryn’s 15,000-square-foot Guitar

House, believed to be the world’s largest green residence, built for

Michael Klein, chief executive of Modulus Guitars. Its 40 rammed-earth

columns look like the neck and frets of a guitar, linking a series of

rooms clad in sprayed earth and reclaimed wood, topped with curved zinc

and solar-powered roofs.

His

more recent work includes the 22,000-square-foot Kirsch Center for Environmental

Studies at De Anza College in Cupertino, Calif., completed last fall

and operated by students. Designed as a teaching tool, the center features

a transparent “truth wall” that lets them study

those working parts of the building usually hidden by finishes. Among

his other outstanding designs is the Real Goods Solar Living Center in

Hopland, Calif., a 5,000-square-foot sustainability compound, completed

in 1996, on what was once a 12-acre barren site. The structures are straw

bale with curved roofs and incorporate passive solar heating and cooling,

photovoltaic and wind electricity generation, and an outdoor oasis cooled

by evaporation. Next came Van der Ryn’s 15,000-square-foot Guitar

House, believed to be the world’s largest green residence, built for

Michael Klein, chief executive of Modulus Guitars. Its 40 rammed-earth

columns look like the neck and frets of a guitar, linking a series of

rooms clad in sprayed earth and reclaimed wood, topped with curved zinc

and solar-powered roofs.

Design for life

In Design for Life, Van der Ryn details the evolution of his views on

linking architecture with nature and culture. He describes how architecture

can create physical and mental barriers that separate us from our world.

The “the soul of architecture,” according to Van der Ryn,

is what we need to recapture to reconnect with our natural surroundings.

“The phrase ‘Design for Life’ has a double meaning,” Van

der Ryn says. “It describes how my life was designed to be and

why, but it also explains how I’ve been designing for life as I

see it, which is making a connection between culture and nature. That’s

what I’ve been doing.” Van der Ryn explains that architecture

can be a series of walls, physical and mental, that compartmentalize

the perception of the world, without connecting to nature. “It

doesn’t have to be that way,” suggests Van der Ryn. “Modernist

buildings can be emotionally cold and lacking sensitivity to their roots

in climate, land, and place. Modernism is optimistic but can be mechanical

and make us less aware of how our natural surroundings affect us, so

I think architecture needs to reconnect in shaping people’s consciousness

with their natural environments.”

“The phrase ‘Design for Life’ has a double meaning,” Van

der Ryn says. “It describes how my life was designed to be and

why, but it also explains how I’ve been designing for life as I

see it, which is making a connection between culture and nature. That’s

what I’ve been doing.” Van der Ryn explains that architecture

can be a series of walls, physical and mental, that compartmentalize

the perception of the world, without connecting to nature. “It

doesn’t have to be that way,” suggests Van der Ryn. “Modernist

buildings can be emotionally cold and lacking sensitivity to their roots

in climate, land, and place. Modernism is optimistic but can be mechanical

and make us less aware of how our natural surroundings affect us, so

I think architecture needs to reconnect in shaping people’s consciousness

with their natural environments.”

Forms follows flow

A main theme in Van der Ryn’s approach is his view that buildings

are not static objects, but organisms, interacting with what’s

around them. He believes “form should follow flow” because

architects need to know first what “life cycles” flow in

an environment before designing a building. This is the basis of his

ecological design strategy, and this also ties in to his position that

architecture needs to factor in human ecology—how people function

with each other in buildings.

“Eco-design is an overlap of meeting human needs while maximizing the continuing capacity of natural systems,” he contends. “The heart of ecological design is the embodiment of the living world we are part of—but often we don’t think that way. Maybe it sounds a little spiritual, but I believe we have a soul—a spirit—and our architecture needs to connect with the soul of the living world. We have all this technology, but what value does it have if we destroy nature in the process? Nature needs to be the model for design.

“Cities are complex ecosystems that can become more fully integrated

with nature. For example, they can produce their own energy and reduce

pollution by consuming and recycling their own wastes. The mission of

green building and sustainable design is to bring architecture and urban

planning back to the flows and cycles of nature. This might be harder

in the city, but I think it is critical for an urban world not to have

nature pushed out of its consciousness.”

“Cities are complex ecosystems that can become more fully integrated

with nature. For example, they can produce their own energy and reduce

pollution by consuming and recycling their own wastes. The mission of

green building and sustainable design is to bring architecture and urban

planning back to the flows and cycles of nature. This might be harder

in the city, but I think it is critical for an urban world not to have

nature pushed out of its consciousness.”

Merging geometry, culture, and nature

To create a design, Van der Ryn uses geometry to integrate space, social

interactions, and landscape. He explains:

“Nature’s geometry is an important organizing principle for ecological design. A building is not a fixed object but part of a larger pattern that flows with change. Both natural and designed places are defined by their physical spaces. Take a natural setting. Although it may look like there are infinite patterns in nature, there are a relatively small number of basic patterns, each of which has a particular function and is connected through flows and cycles, or fractal ecologies, such as where forests meet grassland or where tidal waters meet land—all typical places for biological diversity and productivity. Although they are constantly changing, the process is interlinked and designed to be adaptive. This is sustainability.

“We can apply the same approach to ecological design in our cities

by using adaptive strategies to break down the community and then connect

the dots. Ecological design begins with the intimate knowledge of a particular

place and how it responds to both local conditions and local people,

in other words, being sensitive to the nuances of life and surrounding

environment. Then connect these fractal pieces of nature and people.

This will inform ecologically sound design decisions, such as ways to

regenerate rather than deplete, achieve lower energy costs, create healthier

working environment, and maintain nature. Choices can be made such as

deciding to have sustainable architectural practices that eliminate pesticides,

have rooftop photovoltaic panels that turn the sun into electricity,

or have biological waste treatment using wetlands to oxidize and absorb

excess nutrients in wastewater rather than chemically based systems.”

“We can apply the same approach to ecological design in our cities

by using adaptive strategies to break down the community and then connect

the dots. Ecological design begins with the intimate knowledge of a particular

place and how it responds to both local conditions and local people,

in other words, being sensitive to the nuances of life and surrounding

environment. Then connect these fractal pieces of nature and people.

This will inform ecologically sound design decisions, such as ways to

regenerate rather than deplete, achieve lower energy costs, create healthier

working environment, and maintain nature. Choices can be made such as

deciding to have sustainable architectural practices that eliminate pesticides,

have rooftop photovoltaic panels that turn the sun into electricity,

or have biological waste treatment using wetlands to oxidize and absorb

excess nutrients in wastewater rather than chemically based systems.”

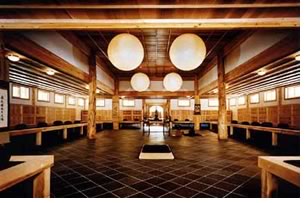

Spatial design needs to have a social consciousness, he says. “The building should be a place where people can come together for interaction, learning, healing, and reflection. Applied science can be limited because there is no assessment of how the building will perform in human terms as a social ecology. Technology suggests we can now make a building with a more intricate configuration that can adapt to meet the needs of the people in it and take advantage of the nature around it.”

Greening the Titanic?

Greening the Titanic?

Van der Ryn believes beauty and harmony are more important than green

standards and sustainability, and that the green architecture movement,

now becoming more mainstream, still needs to keep moving ahead. “It’s

nice to have buildings that reduce energy use and don’t have

toxic materials, but if it is still basically the same old building,

I call that greening the Titanic: the deck chairs might be made from

recycled wood, but we are still heading toward the iceberg. It is not

the ecological design movement of the ’70s anymore where we were

thinking mechanistically. Now we have to keep moving through the second

level of ecological design where beauty and aesthetics are important.

But the word ‘beauty’, to me, always derives from nature.

Architects need to get outdoors and away from their CAD software. Technology

is important and needs to be part of the integration with sustainability

and nature, but I think the era of mechanistic thinking, where the

machine is the metaphor for everything, is falling apart. I think architects

are starting to see we need to do things differently and not stick

with the status quo.”

When working with clients, Van der Ryn says it is act of discovery. “I believe it is truly collaboration. I like to ask clients during a charrette session, ‘What are you trying to create, what are you trying to embody?’ You have to start with the mindset, the aspiration, not the numbers, otherwise it becomes routine and compartmentalized. I like to interview my clients and ask them, ‘What is it you really love? What are you trying to do with this project?’ I am more interested in listening to what they have to say. I also embrace the people involved in the construction. Bringing everyone into the design makes them feel they are part of something bigger and more important then simply working on another job. Everyone becomes invested in ideas and finds ways to improve on them.”

Traditional architecture skills not enough

Traditional architecture skills not enough

As an educator and researcher, Van der Ryn, currently an emeritus professor

at UC Berkeley, played a major role in bringing ecological design awareness

and practices to young architects. While a professor of architecture

at UC Berkeley, a position he held for over 30 years, Van der Ryn was

a key force in establishing Berkeley's international reputation as

a leading school focusing on issues of socially and environmentally

responsible design.

“There is no shortage of science in architecture on structural and mechanical engineering being taught, but social consciousness and natural science aren’t being taught in architecture schools. We must teach young architects how nature connects with built environments, and make them aware of oil dependency and climate change,” Van der Ryn concludes. “The traditional skills being taught are in many cases becoming obsolete because I think architecture is going to change as corporations team up and want new ideas. As a result, architects will have to invent new ways of designing. So, architecture schools can’t fall behind by teaching architecture in the formal sense, or we will become too stuck in the box, literally…The architecture critics still might think this is a fad, but ecological design is now at a much higher level of ecological and cultural integration, well beyond about whether or not the sun can heat water.”

Copyright 2006 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()

![]()