4/2006

In celebration of Earth Day 2006, April 22, the AIA and its Committee on the Environment announce their selection of the top 10 examples of green design that protects and enhances the environment. These projects address significant environmental challenges with designs that integrate architecture, technology, and natural systems. This year’s Top Ten range in scope from a single-family home for the architects themselves to a large corporate headquarters. Interestingly, two are tied to nature preserves and two offer shelter to animals, while the human clientele served by these projects include fledgling nurses, aging Sisters, and elementary school kids.

The eighth annual AIA/COTE initiative was developed in partnership with cosponsors U.S. EPA’s Energy Star® program and the National Building Museum. Hosting the submission and judging forms was BuildingGreen Inc. The projects and their architects will be honored in June at the AIA National Convention in Los Angeles and on May 3 at the National Building Museum in Washington, D.C.

The COTE Top Ten jurors—Kevin Burke AIA, William McDonough + Partners; David Miller, FAIA, The Miller/Hull Partnership; World Green Buildings Council Acting President Kath Williams, PhD, Kath Williams + Associates; Kevin Hydes, PE, Stantec Inc.; Catriona Campbell Winter, The Clark Construction Group; and AIA President-elect RK Stewart, FAIA, Gensler—considered 10 metrics for each project:

- Sustainable Design Intent & Innovation

- Regional/Community Design & Connectivity

- Land Use & Site Ecology

- Bioclimatic Design

- Light & Air

- Water Cycle

- Energy Flows & Energy Future

- Materials & Construction

- Long Life, Loose Fit

- Collective Wisdom & Feedback Loops.

This year’s Top Ten Green Buildings are:

Alberici Corporation Headquarters, Overland, Mo., by Mackey Mitchell

Architects

Alberici Corporation Headquarters, Overland, Mo., by Mackey Mitchell

Architects

This adaptive reuse of an existing manufacturing plant into a corporate

headquarters for one of St. Louis’ oldest and largest construction

companies mandated inclusion of an open office environment, structured

parking, training rooms, exercise facilities, and dining facilities.

When company growth led to the decision to move, the CEO requested to

be in a place that “fosters teamwork and creativity.” Fitting

the bill was a 13.6-acre brownfield site with a 1950s office building

and 150,000-square-foot former metal manufacturing facility. With 70-

and 90-foot clear-span bays and at 505 feet long, it was a “cathedral

of steel.” The interiors are organized around three large atria

and receive abundant light, fresh air, and views to the outdoors. In

addition to visually uniting the two floors, the atriums act as thermal

flues to induce ventilation. The open plan environment fosters teamwork

and collaboration, while affording 90 percent of building occupants direct

views to the outdoors. The project achieved LEED™ Platinum level

certification from the USGBC, with 60 of 69 points, the highest total

ever.

The Animal Foundation Dog Adoption Park, Las Vegas, by Tate Snyder Kimsey

Architects

The Animal Foundation Dog Adoption Park, Las Vegas, by Tate Snyder Kimsey

Architects

Driven by a need to expand its operations, the Animal Foundation is developing

plans to create a regional animal campus to take care of the animal sheltering

and adoption needs for Las Vegas, North Las Vegas, and surrounding Clark

County. The project's first phase was this dog adoption park, which consists

of “dog bungalows” containing 12 kennels each, outdoor runs,

and a visitation room. The architects arranged the bungalows in a park-like

setting shaded by freestanding canopies supporting photovoltaic panels.

The goals for the dog adoption park were to create a dignified way of

presenting animals to the adopting public and use sustainable strategies

in the design of this complex, with the intention of achieving a USGBC

LEED Platinum certification. Given southern Nevada’s climate, the

design team identified reducing the cooling load and water use as the

two major areas of focus. The demands of proper canine husbandry led

to unexpected synergies between the health needs of the dogs and reductions

in energy and water use. Canines thrive in natural daylight and fresh

air; consequently, the bungalow’s form and orientation are governed by

daylighting and wind-powered ventilation.

Ballard Library and Neighborhood Service Center, Seattle, by Bohlin

Cywinski Jackson

Ballard Library and Neighborhood Service Center, Seattle, by Bohlin

Cywinski Jackson

This project consists of a 15,000-square-foot library, 3,600-square-foot

neighborhood service center, and 18,000 square feet of below-grade parking.

Its district, rapidly becoming the civic core of the neighborhood, is

easily accessible for pedestrians, bicycles, and public transit. A pedestrian

zoning overlay was recently adopted to promote development of this nature.

The public nature of this building dictated a collaborative process among

the architect, Seattle Public Library, Neighborhood Service Center, community,

and various user groups. The building itself represents a powerful civic

face along a pedestrian corridor. The main entry, pulled back from the

street, makes a deep front porch, joining the library and the service

center under a large canopy. A gently curving roof, planted with sedums

and grasses, absorbs water, thus reducing runoff. A periscope and observation

deck invite visitors to engage in the green roof’s ecology above

the street. The architect maximized the use of varying intensities of

natural light, while metered, photovoltaic glass panels shade the center’s

lobby and demonstrate the effectiveness of photovoltaics in the Pacific

Northwest.

Ben Franklin Elementary School, Kirkland, Wash., by Mahlum Architects

Ben Franklin Elementary School, Kirkland, Wash., by Mahlum Architects

The architects designed this new, 56,000-square-foot elementary school

to connect students directly with the environment in which they live.

The school replaces an existing facility on a narrow 10-acre north-south

site. The surrounding residential neighborhood, interlaced with equestrian

trails, horse paddocks, and forested lands, includes a mature stand

of Douglas fir that covers the northern third of the property. This

rich natural setting and a requirement to maintain operation of the

existing school during construction led to the new facility’s

location at the center of the site, embracing the woods. Inside, the

school’s 450 students in grades K-6 participate in small learning

communities formed by clusters of four naturally ventilated and daylighted

classrooms around a multi-purpose activity area. Stacked within two-story

wings that extend towards the woods, these communities link integrally

with views and access to nature beyond.

Philadelphia Forensic Center, Philadelphia, by the Croxton Collaborative

Architects PC, with associate architect Cecil Baker Associates

Philadelphia Forensic Center, Philadelphia, by the Croxton Collaborative

Architects PC, with associate architect Cecil Baker Associates

This new forensics science center for the Philadelphia Police Department

is both a state-of-the-art forensics laboratory facility and a demonstration

project for green design. The rigorous program includes a firearms unit,

with a shooting range for ballistics analysis; a crime-scene unit for

gathering evidence; and chemistry, criminalistics, and DNA laboratories.

The building is housed in a former 1929 concrete-frame, brick-infill

K-12 school building on a site that had been abandoned for many years.

The architects incorporated myriad sustainable features, including: precise

mapping and load separation of areas requiring 100 percent outside air

to minimize mechanical loads, envelope upgrades resulting in a super-insulated

building, “clean” products and finishes resulting in vastly

improved indoor air quality, deep daylighting achieved by ceiling configurations,

a rooftop photovoltaic array providing 15 kW, and primary access to all

mechanical and infrastructure systems outside of lab areas. The project

also substantially increases pervious areas of the site, with vegetated

swales providing bioremediation of runoff and reduction of input into

city sewers.

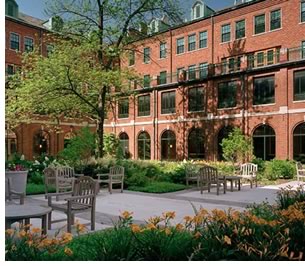

The Renovation of the Motherhouse, Monroe, Mich., by Susan Maxman and

Partners

The Renovation of the Motherhouse, Monroe, Mich., by Susan Maxman and

Partners

When the Sisters, Servants of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, recognized

that their order was diminishing, they asked the design team to embark

on a collaborative, long-range planning process to determine the best

way to achieve an ecologically sustainable 21st century community on

their 280-acre site in southern Michigan. Many of the 1930s structures

on their property are historically significant, so any proposed rehabilitation

required review by the State Historic Preservation Office. A number of

the Sisters require some assistance, and those needs were not being met

in the current facility, which was originally designed for dormitory-style

living for young women, not for frail elderly residents. The design team

met the complex programmatic challenge by designing 380,000 square feet

of construction that used the existing structures to best meet the owner’s

very specific housing, long-term care, and spiritual needs while achieving

sustainable and preservation goals, especially incorporation of daylight,

views, and natural ventilation. The team also succeeded in making this

austere former convent into a warm and friendly home, with a strong focus

on nature and the surrounding site.

School of Nursing and Student Center, the University of Texas Health

Science Center at Houston, by BNIM Architects

School of Nursing and Student Center, the University of Texas Health

Science Center at Houston, by BNIM Architects

This new building offers a pedagogical model of wellness, comfort, flexibility,

environmental stewardship, and fiscal responsibility. It is another step

in the direction of healthy, environmentally responsible actions that

the university began with changes to facilities operations to reduce

the use of energy, polluting chemicals, cleaning agents, potable water,

and other resources. The architects adapted the program to accommodate

the need for study and support spaces by the unusually high percentage

of graduate students in the program. Flexible building elements, such

as raised floor and demountable partitions, allowed for revisions to

the interior design to accommodate the higher population mandated by

the state government during the design process. As a facility that teaches

health-care professionals, the building was designed as a healthy indoor

environment: all major spaces have operable windows, views to the outside,

and daylight as an ambient light source. Interior meeting rooms and workspaces

open onto three atriums that provide controlled diffuse daylight.

Solar Umbrella, Venice, Calif., by Pugh + Scarpa

Solar Umbrella, Venice, Calif., by Pugh + Scarpa

Nestled in a neighborhood of single- and two-story bungalows, the Solar

Umbrella Residence boldly establishes a precedent for the next generation

of California Modern architecture for this architect couple and their

six-year-old son. The architects used Paul Rudolph's 1953 Umbrella

House as inspiration for a contemporary reinvention of the solar canopy.

Taking advantage of the unusual through lot, the addition shifts the

residence 180 degrees from its original north orientation toward the

south and rich Southern California sunlight. Conceived as a solar canopy,

89 amorphous silicon solar panels protect the body of the building

from thermal heat gain. This solar skin absorbs and transforms the

light into usable energy, providing the residence with 95 percent of

its electricity. The existing 1923 600-square-foot structure was retained

and remodeled, and, even though the completed structure is three times

its original size, the net increase in lot coverage is less than 400

square feet.

Westcave Preserve: Warren Skaaren Environmental

Learning Center, Dripping Springs, Tex., by Jackson & McElhaney

Westcave Preserve: Warren Skaaren Environmental

Learning Center, Dripping Springs, Tex., by Jackson & McElhaney

This 30-acre nature preserve and canyon 28 miles northwest of Austin

expanded its community programs by building a new “wilderness classroom” and

providing a meeting place for walking tours to a nearby waterfall and

grotto. The goal of the project was “to foster the respect and

stewardship of the natural environment, provide environmental education,

and preserve this sanctuary into the future.” The architects conceived

the building as a “three-dimensional textbook” and framework

for analogies between building materials and systems and how they mimic

or model natural systems. For instance, water quality and water cycles

are demonstrated through a rainwater collection and filtration system,

while a wetland and self-composting toilets wastewater systems show recycling

of materials in nature. Sustainable energy systems, including a photovoltaic

array, ground source heat pumps, and daylighting are integrated into

the building. An exhibit embedded into the terrazzo floor illustrates

the enigmatic relationship between the Fibonacci Series, golden rectangle,

logarithmic curve, and the form of a 90-million-year-old ammonite.

World Birding Center, Mission, Tex., by Lake/Flato

World Birding Center, Mission, Tex., by Lake/Flato

Texas’ Lower Rio Grande Valley, one of the richest bird habitats

in the world, over the past century has seen suburban and agricultural

developments so severely affect the landscape that only 5 percent of

the native scrub habitat currently remains. Through a joint effort of

the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department and the local communities, the

World Birding Center was established to “significantly increase

the appreciation, understanding, and conservation of birds and wildlife

habitat.” The World Birding Center headquarters site forms a gateway

out of disturbed land and sits adjacent to more then 1,700 acres of remnant

native habitat that is being reclaimed and established as a habitat preserve.

Through the process of “right sizing,” the architects reduced

the building’s original program for 20,000 square feet down to

13,000. The plan specified that all landscaping use only native plants

and incorporated a 47,000-gallon rainwater system—integrating rainwater

guzzlers, natural pools, and water seeps—to provide much-needed

water for birds and butterflies.

Copyright 2006 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()

![]()