4/2006

Is the Grass Always Greener?

by Nadav Malin and

Jessica Boehland

Excerpted

from Environmental Building News

In little more than a decade,

bamboo flooring has become a serious contender in the hardwood flooring

market, and some believe that bamboo plywood is next. Lauded in environmental

circles for its quick growth and the fact that it can be harvested

without harming the plant, bamboo seems almost too good to be true.

In fact, like any product, it has its downsides. “There

is a lot of mythology about bamboo,” says Manuel Ruiz-Perez, professor

of ecology at the Autonomous University of Madrid, who has been researching

bamboo for more than 10 years. “You have to be cautious.” Now

that bamboo flooring has grown beyond niche market status, it is beginning

to attract more scrutiny.

In little more than a decade,

bamboo flooring has become a serious contender in the hardwood flooring

market, and some believe that bamboo plywood is next. Lauded in environmental

circles for its quick growth and the fact that it can be harvested

without harming the plant, bamboo seems almost too good to be true.

In fact, like any product, it has its downsides. “There

is a lot of mythology about bamboo,” says Manuel Ruiz-Perez, professor

of ecology at the Autonomous University of Madrid, who has been researching

bamboo for more than 10 years. “You have to be cautious.” Now

that bamboo flooring has grown beyond niche market status, it is beginning

to attract more scrutiny.

The most common use of bamboo in North American construction has, by far, been as a flooring material. In 1997 Environmental Building News found only eight companies supplying the North American market. In contrast, about 200 companies imported about 45 million square feet of bamboo flooring into the U.S. in 2005, estimates David Knight, president and CEO of Teragren, LLC (formerly Timbergrass), in Bainbridge Island, Wash. That represents about 2 to 3 percent of the market for wood floors, according to Knight.

One of the largest North American bamboo distributors, Teragren, has achieved its distribution scale by selling through retail flooring outlets—it has product in 1,700 stores in the U.S. and Canada and hopes to be in 3,000 by the end of 2006, he says. Like many of the other reputable importers, Teragren has an exclusive relationship with a producer in China—that producer now has three factories and more than 500 employees, and Teragren handles two-thirds of its production (the rest goes to France and various outlets in Asia).

Varieties. Bamboo flooring comes in several varieties. First, it can be solid or engineered. Solid bamboo is not solid planks of bamboo, as the name implies, but rather strips made up of distinct layers of bamboo. Engineered flooring is made of a bamboo top layer glued to one of a variety of materials. For the “solid” products, the surface bamboo can be oriented either vertically or horizontally. Horizontal-grain (aka, flat-grain) flooring is the more traditional look and features bamboo’s characteristic nodes, or “knuckles.” Vertical-grain (edge-grain) flooring, on the other hand, has the bamboo strips lined up on edge, resulting in a more uniform look and reducing the knuckle appearance.

Bamboo flooring is commonly sold in two color tones: a light blond (bamboo’s

natural color) and a darker hue, often described as “carbonized.” The

darker color comes from heat-treating the bamboo, which actually caramelizes

the sugars in the fiber. Bamboo flooring can also be stained. Bamboo

Hardwoods, for example, offers “cherry” and “fruitwood” colors

for its premium floors.

Bamboo flooring is commonly sold in two color tones: a light blond (bamboo’s

natural color) and a darker hue, often described as “carbonized.” The

darker color comes from heat-treating the bamboo, which actually caramelizes

the sugars in the fiber. Bamboo flooring can also be stained. Bamboo

Hardwoods, for example, offers “cherry” and “fruitwood” colors

for its premium floors.

Within the last few years, several bamboo flooring companies have introduced strand products, made by separating the bamboo into individual fibers and then binding them under heat and pressure with a phenol-formaldehyde resin. Smith & Fong calls its version Plyboo® Strand™ flooring, and Sustainable Flooring, LLC, calls it Strandwoven bamboo. Teragren offers its Synergy strand product.

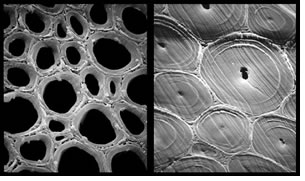

Hardness. One factor that differentiates high-quality bamboo flooring and plywood from lower-quality products is the age at which the culms were harvested. Moso bamboo culms emerge from the ground at their full dimension of up to eight inches. They spend the next several years “hardening their arteries,” whereby the capillaries thicken toward the inside, but the diameter never changes. What begins as almost entirely sugar and water lignifies into hard cellulose.

Although three-year-old culms can be made into flooring, some companies claim to harvest only after five years. According to Knight, “We can see that younger than five or six years, the fibers aren’t as long. The longer the fiber, the better the stability.” Dan Smith, founder of Smith & Fong, agrees, noting, “I interpret the six-year point as the maximum apex for strength and for keeping the resource healthy.” Others, including Doug Lewis, founder of Bamboo Hardwoods, believe bamboo reaches its peak hardness at about three years and doubt whether there is any benefit to letting it age further.

Lewis also questions whether it’s possible to ensure that only older culms are used. “I couldn’t tell if a pole is much beyond three years,” he told EBN. Smith admits that ensuring the use of older culms is difficult. “I don’t think there’s any way to control, to say ‘I want six-year growth’,” he says. Trevor Gilmore, of Bamboo Mountain, Inc., agrees, noting, “The purchasers have to have a really good relationship with the manufacturers they work with.”

Although it is hard to tell a pole’s age by looking at it, most bamboo farmers actually track their plants carefully. Culms are often marked with a name and date after their first year, when they’ve reached full size. Some companies even use electronic tagging systems. “We go to the farmer and purchase it from him after the first year. We put our name and ID chips into it and know it’s ours,” says David Kurland, of Mill Valley Bamboo Associates.

While bamboo flooring products are lauded for their hardness, the actual

hardness of the available products varies substantially. The age at which

the culms are harvested plays a role—flooring from less-reputable

distributors may be made from culms younger than three years old, so

the resulting product dents easily. The bamboo variety is also important. “We

could actually dent it with our fingernail,” Knight says of a competitor’s

product that he believes is made of a subspecies of moso bamboo.

While bamboo flooring products are lauded for their hardness, the actual

hardness of the available products varies substantially. The age at which

the culms are harvested plays a role—flooring from less-reputable

distributors may be made from culms younger than three years old, so

the resulting product dents easily. The bamboo variety is also important. “We

could actually dent it with our fingernail,” Knight says of a competitor’s

product that he believes is made of a subspecies of moso bamboo.

Various manufacturing processes also affect the hardness of the finished product. Notably, heating bamboo to caramelize it softens the fibers. Teragren’s vertical-grain caramelized flooring is rated at 1,470 newtons on the Janka hardness test, compared with 1,850 for the same product in the natural color. (Red oak scores about 1,360 on the same test.) The difference is less dramatic in the flat-grain configurations, but caramelizing still reduces the hardness by about 10 percent. Strand bamboo, on the other hand, is much harder than conventional bamboo flooring and generally considered appropriate for commercial and other high-traffic areas. Smith & Fong and Teragren both claim their strand flooring is twice as hard as red oak, and Sustainable Flooring describes it as “bomb-proof.”

Manufacturing and transportation considerations

Manufacturers of bamboo flooring and plywood handle potentially toxic

chemicals, including binders and finishes; produce a lot of solid waste;

and run equipment that emits combustion gases. How responsible the

manufacturers are in dealing with these potential environmental and

health hazards is unclear.“A lot of these companies are dumping finish down the

drain at the end of the day,” says Ryan Wuest of iFloor.com.

Wuest notes that iFloor didn’t always look into its manufacturers

as carefully as it does now. “Once we found out what [our previous

suppliers] were doing, we didn’t want anything to do with them,” he

says. Most major North American distributors of bamboo flooring and

plywood claim to work with only reputable manufacturers and tout their

long-term relationships with those producers in vouching for their

commitment to quality and environmental responsibility.

Several bamboo flooring companies in the U.S., including Teragren and

Mill Valley Bamboo, go a step further, noting that the manufacturers

they work with are registered under the International Organization for

Standardization (ISO) standards 9001 for quality control and 14001 for

environmental management systems (EMS). In principle, ISO 14001 registration

means that an accredited, independent auditor has reviewed the company’s

EMS for compliance with the ISO standard and conducted site visits to

confirm that the EMS is being implemented appropriately. In practice,

however, the significance of these ISO registrations in China is not

so clear. ISO-accredited auditors from Europe and North America are not

welcome in China, apparently because they are too demanding, according

to Jason Morrison, director of the Pacific Institute’s Economic

Globalization and the Environment Program. “I’ve heard first-hand

from a registrar that they have been blacklisted from doing certifications

in China,” Morrison reports. Instead, the Chinese government is

accrediting its own registrars to ensure that Chinese companies can get

registered. “They see it as a market-access issue,” says

Morrison, noting that being registered for ISO 9001 and ISO 14001 is

considered a prerequisite for supplying some North American and European

companies.

Several bamboo flooring companies in the U.S., including Teragren and

Mill Valley Bamboo, go a step further, noting that the manufacturers

they work with are registered under the International Organization for

Standardization (ISO) standards 9001 for quality control and 14001 for

environmental management systems (EMS). In principle, ISO 14001 registration

means that an accredited, independent auditor has reviewed the company’s

EMS for compliance with the ISO standard and conducted site visits to

confirm that the EMS is being implemented appropriately. In practice,

however, the significance of these ISO registrations in China is not

so clear. ISO-accredited auditors from Europe and North America are not

welcome in China, apparently because they are too demanding, according

to Jason Morrison, director of the Pacific Institute’s Economic

Globalization and the Environment Program. “I’ve heard first-hand

from a registrar that they have been blacklisted from doing certifications

in China,” Morrison reports. Instead, the Chinese government is

accrediting its own registrars to ensure that Chinese companies can get

registered. “They see it as a market-access issue,” says

Morrison, noting that being registered for ISO 9001 and ISO 14001 is

considered a prerequisite for supplying some North American and European

companies.

The fossil fuels required to move bamboo products halfway around the world constitute an environmental strike against the product, although oceangoing freighters move material more efficiently than trucks. No North American companies are currently growing bamboo for building uses, and, due primarily to the high cost of labor in North America relative to the parts of the world where bamboo is currently grown for building uses, this situation is unlikely to change.

Copyright 2006 BuildingGreen Inc.

Copyright 2006 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()

This article is excerpted from Environmental Building News, a publication of BuildingGreen Inc.

(AIA members get a 30% discount on Building Green Suite subscriptions.)

The full-text article, including a more detailed analysis of the environmental pros and cons of bamboo, is available on the BuildingGreen Web site.

![]()