3/2006

by Stella Tarnay

by Stella Tarnay

In early 2005, Mayor Clare Higgins of Northampton, Mass., was looking for a way to jump-start her city’s comprehensive planning process. Many issues had changed since the last plan was completed in 1973. The bucolic Massachusetts town was becoming a victim of its own success. Development was encroaching on open space, housing affordability was threatened, and the city’s energy costs were going through the roof. The city needed a vision for a viable, sustainable future. “We had a lot of discussion about money,” says Higgins, “but I felt we also needed a long-term view of where we were going.” Higgins, who drives a hybrid, wanted to make Northampton a model for sustainable development.

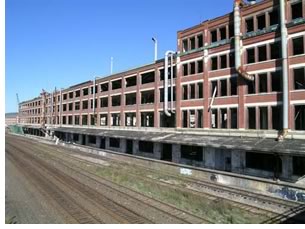

In nearby Berkshire County, Pittsfield Mayor James M. Ruberto and his planning team faced a different set of challenges. The departure of General Electric (GE) in the 1980s led to the exodus of a quarter of the city’s population and drained the life out of this once bustling industrial town. “We were a city that had a proud history of industrial innovation. When GE left, we lost our center, our identity,” says Ruberto. Further, the GE legacy included environmental problems such as brownfields and polluted waterways—additional stigmas for the city to overcome. By early 2005, the city’s new mayor and the residents of Pittsfield were primed to give their community a new start. The questions that Ruberto and Pittsfield’s citizens faced were: How could the city provide diverse economic opportunity for present and future generations of its residents while preserving Pittsfield’s valuable natural resources? What would a vital, culturally rich community look like? Like Northampton, the city was about to launch a master planning process as it sought answers to these and other questions.

New AIA SDAT program helps define the future

New AIA SDAT program helps define the future

Ruberto in Pittsfield and Higgins in Northampton, with their planning

directors, turned to the AIA

Center for Communities by Design to help

them envision a viable, sustainable future for their cities. Theirs

were two of six communities to receive grants and an expert team from

the AIA through the new Sustainable Design Assessment Team (SDAT) program,

which is based on the principle that environmental, social, and economic

systems are interconnected and that decisions should be made with the

well-being of future—as

well as today’s—generations in mind. “Many communities

want to become more sustainable but are immobilized by conflicting

agendas, politics, personalities, or an overabundance of information,” says

Peter Arsenault, AIA, a national board member and SDAT volunteer. “Many

communities don’t really know what assets they have or have not

yet examined their own policies in terms of how they affect their future.” Still

others, he notes, know the issues and even have a view toward their

goals, but need help mapping out a plan to get there.

As part of their application to the SDAT process, communities are asked to consider their assets and weaknesses and identify critical issues they would like expert assistance with as well as key stakeholders and participants. Each community forms a local steering committee that partners with the SDAT and provides a cash match to the process. AIA staff and the designated team leader then make an initial scoping visit. This is followed by a three-day charrette by the SDAT team, stakeholders, and the community at large. Team members tour the city or town, meet with local leaders and citizens, conduct extensive listening sessions, facilitate roundtable discussions on designated focus issues, and host a public meeting. At the end of the charrette, the team provides a public assessment of the community’s assets and challenges, articulates both visually and in words an emerging public vision, and offers preliminary recommendations and strategies for moving forward toward a more sustainable future. This is followed by a more formal written report to the community.

Northhampton leans toward an ecopark and smaller green spaces

Erica Gees, president of AIA Western Massachusetts, helped the two Massachusetts

communities apply for and receive the SDAT grants. She thinks architects

are uniquely qualified to help cities like Pittsfield and Northhampton

envision sustainable futures. “Architects are in a unique position

to seen and understand diverse issues in a holistic manner and design

integrated solutions,” she says. “With this view, you really

can create better environments.”

Northampton

identified land use, smart growth, economic development, and energy use

as their major issues. The Northampton team included an architect with

expertise in housing affordability, an architect who specialized in energy

conservation, a land use planner, an economic development specialist,

a transportation expert, and a landscape architect who had worked on

open space issues. Team Leader Arsenault came to the charrette with more

than 20 years of experience in green building and green neighborhood

design. During their initial scoping visit, Arsenault and Ann Livingston,

director, AIA Center for Communities by Design and manager of the SDAT

program, toured the city, met with local leaders, and made sure conditions

on the ground matched the application. They worked with the mayor and

Northampton’s local steering committee—as

well as the regional AIA—to plan the three-day charrette.

Northampton

identified land use, smart growth, economic development, and energy use

as their major issues. The Northampton team included an architect with

expertise in housing affordability, an architect who specialized in energy

conservation, a land use planner, an economic development specialist,

a transportation expert, and a landscape architect who had worked on

open space issues. Team Leader Arsenault came to the charrette with more

than 20 years of experience in green building and green neighborhood

design. During their initial scoping visit, Arsenault and Ann Livingston,

director, AIA Center for Communities by Design and manager of the SDAT

program, toured the city, met with local leaders, and made sure conditions

on the ground matched the application. They worked with the mayor and

Northampton’s local steering committee—as

well as the regional AIA—to plan the three-day charrette.

The charrette itself engaged hundreds of citizens and more than 100 issue-focused stakeholders. One public meeting even involved the participation of a second-grade class that was taking part in the AIA’s Learning by Design program. It became evident early on to the team that Northampton residents did not fully appreciate the internal contradictions of some of their public decisions, nor the vital community assets they enjoyed. For example, says Arsenault, “They wanted to support local business activity and growth while other decisions were making it virtually impossible for business to expand on open land.”

On the third day, the SDAT team presented their findings, which incorporated

an assessment of strengths and weaknesses in the focus areas, emerging

visions of long-term sustainability, and recommended strategies for getting

there. The SDAT also highlighted creative solutions that had started

to emerge as advocates from different arenas began to talk to each other

in an integrated way.

On the third day, the SDAT team presented their findings, which incorporated

an assessment of strengths and weaknesses in the focus areas, emerging

visions of long-term sustainability, and recommended strategies for getting

there. The SDAT also highlighted creative solutions that had started

to emerge as advocates from different arenas began to talk to each other

in an integrated way.

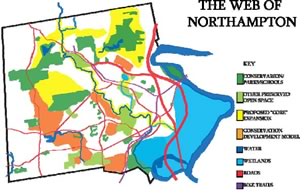

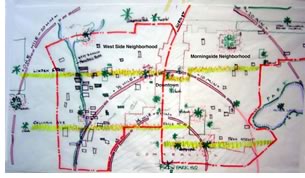

One local opportunity focused on redevelopment of Hospital Hill, a former mental health institution with existing buildings and large remaining tracts of land. During discussion, participants began envisioning a mixed-use ecopark developed on the site from existing buildings and infill construction. A second emerging vision was a series of connected, smaller green spaces throughout the city, linked by walking and biking paths and natural stormwater treatment buffers. The team’s experts advised residents that smaller linked green pocket parks could give more access to green space than isolated large lots within the city.

For Mayor Higgins, the biggest benefit of the SDAT process has been the stage it has set for ongoing dialogue. “Our future vision is still very much a work in progress,” she says. “The charrette was a great way to start talking about it.” The city’s public planning will continue with a series of nine neighborhood focus groups and an ongoing comprehensive planning process. Planning staff expect to have the new master plan completed by October 2006, with implementation to start right away.

Pittsfield rediscovers its historic past

Pittsfield rediscovers its historic past

Pittsfield identified four focus issues: housing, natural resources,

general land use, and development. More generally, says Deanna Ruffer,

Pittsfield’s planning director, “we needed a diagnostic

look at the relationship between development and natural resources.” In

Pittsfield, the SDAT process focused more directly on economic development

and resource use. Community discussions and the team’s own analysis

emphasized the importance of diversity—not just for ecological

systems, but for the city’s economy and culture as well. “The

days of the one-company town are over,” says Ruffer. “The

SDAT process confirmed for us that we needed to focus on midsize companies

and diverse industries.”

The team supported the city’s resolve to create an urban greenway and helped residents see the value of its neighborhoods through this process. The focus of public conversation shifted from greenfields development to restoration and redevelopment of the city’s historic buildings and infrastructure. “The planning and visioning helped us see ourselves and confirm our visions of ourselves as the downtown of the Berkshires. We’re not going to succeed by ruralizing ourselves,” says Mayor Ruberto. “We have good bones. We need to build on that.”

A key benefit of the SDAT program appears to be the opportunity it offers to a community to see itself with fresh eyes. Local enthusiasm for SDAT was reflected in the unusual level of media coverage the team’s visits received in Pittsfield. The charrette attracted radio and TV coverage and made the local radio shows and the front page of Pittsfield’s newspaper. The planning staff expects to have the new master plan completed by October of this year, with implementation to start right away. In Pittsfield, city staff members are focusing on planning for diversified economic development that builds on existing infrastructure, including a downtown arts and entertainment center.

Copyright 2006 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()

Stella Tarnay is a planner and a writer based in Washington, D.C.

The AIA Center for Communities

by Design has selected eight communities

to receive technical assistance under the S/DAT program in 2006. The

AIA is providing $15,000 to cover the expenses of SDAT-related activities,

and the communities will provide a $5,000 match (and cover costs in

excess of $20,000).

• Hagerstown, Md.

• New Orleans

• Syracuse

• Longview, Wash.

• Guemes Island, Wash.

• Lawrence, Kan.

• Northeast Michigan

• Northern Nevada.

For more information and the full report on these SDATs, visit

the SDAT portion of the AIA Web site.

![]()