3/2006

From more than 15 years of experience working in Korea, China, Vietnam, the Philippines, Japan, and Russia, Parker Durrant International, part of the Durrant Group Inc., has gained a considerable amount of experience in the highlights and cautionary elements of getting involved in these very exciting, very hot markets. Because I’d have liked to have had some forewarning of what this endeavor entails myself, I have put together a list of 10 starting points for any firm considering these markets. I will follow with a more detailed discussion of the first five, which, because the points are so intertwined, will actually cover all 10.

Ten lessons learned

- Lack of a defined program is common in Asian projects. Clients often look to American architects to generate the program as the design is progressing.

- Asian-project construction budgets are occasionally flexible. Ideas are valued more than budget. If the idea is good, the idea sets the precedent for the project budget.

- Get part of your fee up front. Understand payment methods and additional fees. Learn U.S. tax treatment of each country.

- Local associated architects and engineers are quick learners and hard workers.

- American architects have more freedom in their design expression in Asia than they do in the U.S.

- As designers, we should respect and learn the local culture, as well as the local design process.

- Asian clients demand more design ideas and options than clients in the U.S.

- Generally, Asian building codes cannot deal with the design of mega projects; they are open to U.S. codes or the IBC.

- Layers of decision-making hierarchy can cause project delay and indecision. Try to work at the highest level.

- Symbolism in Asia plays a greater role in building design.

Some quick background

Some quick background

Parker Durrant International broke into the Korean market through a combination

of successes. One was our first plunge into international work with

the new U.S. Embassy in Santiago, Chile, which we started in 1986 and

completed in 1994. Concurrently, Stephan Huh, FAIA, who now is the

chairman of Parker Durrant International, was successful in

getting our work published in a Korean magazine—he would send

descriptions and photographs of our work in the West, and they accepted

them for publication. Over the course of several years, those articles

established Parker Durrant in Korea as a recognized name in major Western

high-design projects, which was seen by Korean architects as a leg

up, so we were invited to join in competitions there for major projects—30

competitions netted us 20 projects, many of which are now built.

In many markets overseas, clients are looking for innovative, signature design work. They also appreciate our knowledge of specialty facilities, such as medical facilities. But what they are importing mainly is high-rise, high-design expertise. That is why our services to Asian clients are most often limited to predesign analysis and schematic design, but often with the added scope of checking design documents and working drawings for adherence to the design intent.

There are many ways to break into international design, and one would be to find a firm with an established client base overseas who could use your talents, even if only temporarily. Parker Durrant International has partnered with smaller high-design firms in that way, when work gets overwhelming. There is nothing like experience to develop your own firm’s international marketability.

Define a program for the client

Define a program for the client

In the U.S., we usually have a program and a feasibility study before

we start schematics. Clients in our Asian markets start with a larger

vision, which they articulate much more succinctly, often in a one-page

summary. And there usually isn’t time or opportunity for us to

sit down and talk with all the department heads and other key people.

Not knowing in detail what you are being asked to design can lead to

many difficulties, of course, and can be frustrating because we’re

used to the needs assessments and other direction given in the facility

program.

We were finding ourselves generating the program as we were designing the project. And what we’ve found is that even though clients may not understand how to define a comprehensive program, they are willing to look to us to generate one. So what we do now is negotiate feasibility services as part of our compensation package before we commence on a project.

To get the project going in the meantime, we have a very preliminary program, get them to understand that this is what we’re starting with, and then we proceed.

Communication, as always, is a basic problem to address. Language skills

themselves are not the main impediment, though. In the Chinese, Koreans,

and Vietnamese organizations with which we have worked, there is always

at least one bright person who speaks English very well, and they become

the link. So it’s not the language barrier, per se, but rather

how concepts are translated. To overcome this complication, you have

to repeat yourself a couple of times in different ways to make sure the

understanding is two-way and complete. Of course, this is good practice

regardless of who the client is.

Communication, as always, is a basic problem to address. Language skills

themselves are not the main impediment, though. In the Chinese, Koreans,

and Vietnamese organizations with which we have worked, there is always

at least one bright person who speaks English very well, and they become

the link. So it’s not the language barrier, per se, but rather

how concepts are translated. To overcome this complication, you have

to repeat yourself a couple of times in different ways to make sure the

understanding is two-way and complete. Of course, this is good practice

regardless of who the client is.

If the idea is good, budget follows

One of the many bright spots in doing work in Asia is that ideas are

valued more than a set budget. The people in China who are driving

speculative development—the clients who usually come to us—are

very well-to-do and decision making tends to be highly centralized.

The first two Chinese clients we worked with were both millionaires

with considerable additional backing from their equally wealthy partners,

and they didn’t have a set budget. I said to Steve Huh as we

were going out my first time, “You mean you don’t know

what the budget is on this?” He said, “Don’t worry,

they’re very flexible. You tell them what fits on the site and

how it looks, and they’ll accommodate a budget.”

Compare that with a university client here who will have a very specific

budget firmly set by the state legislature. In one case, the state gave

our client the land for free—three blocks in Dalian, China—with

the expectation that they would develop it. He and his investor friends

realized they couldn’t lose with this investment as long as it

was top-flight quality design. So they choose their architecture firm

or partnership of firms based on their perception of design quality.

They chose us for that 3-million-square-foot mixed-use center because

we got them involved in the design process, which gave them confidence

in us.

Compare that with a university client here who will have a very specific

budget firmly set by the state legislature. In one case, the state gave

our client the land for free—three blocks in Dalian, China—with

the expectation that they would develop it. He and his investor friends

realized they couldn’t lose with this investment as long as it

was top-flight quality design. So they choose their architecture firm

or partnership of firms based on their perception of design quality.

They chose us for that 3-million-square-foot mixed-use center because

we got them involved in the design process, which gave them confidence

in us.

Large Korean civic projects are mostly chosen through competitions these days. They have a group of about 200 selected professors, and any time there is a government project, they call 12 or 15 professors who independently judge these projects. It’s the only way to make it above board. And key to them is identifying the best possible design.

So the firm whose ideas are selected can be fairly certain that those ideas carry intrinsic value that will in turn set the budget. If your idea is chosen as the best, the client will extend the site—buy the adjacent site—to do what you are suggesting. It’s an unbelievable relationship.

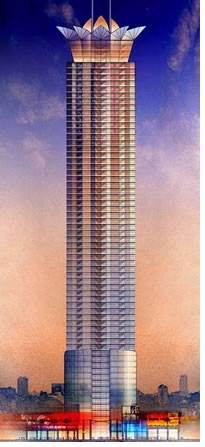

The Trinity Tower in Seoul is an example of what the client receives in turn. It has become a signature piece of architecture because you see it as you come and go to the airport. It towers over the visitor and leaves a strong, positive impression. So much so, as it turns out, that many other architects have copied it for other parts of Korea.

Profitability means, first, getting paid

We’ve learned that we need to get our money up front—or at

least as much of it as possible. Some of the very large and well-known

architects have considerable leverage and corporate stability get a pretty

large chunk of money up front—30 or 40 percent—before they

start the project. If the client is serious, they’ll make that

commitment and pay you. We write the contract so there’s a down

payment of at least 20 percent before we even start, and we’ve

been successful both in Korea and China.

The payment methods in these Asian markets are not hourly, and our clients

there do not understand the concept of additional fees. They pay when

a specific phase is completed. Usually we provide the front-end design

services, so we negotiate a preliminary payment, an interim payment,

and the final payment. There may be a fourth payment if we are also involved

in design development. In negotiations, we define a series of deliverables.

When we deliver them, they pay us.

The payment methods in these Asian markets are not hourly, and our clients

there do not understand the concept of additional fees. They pay when

a specific phase is completed. Usually we provide the front-end design

services, so we negotiate a preliminary payment, an interim payment,

and the final payment. There may be a fourth payment if we are also involved

in design development. In negotiations, we define a series of deliverables.

When we deliver them, they pay us.

If you do sense that payment is not forthcoming, act accordingly. We have one client who has been withholding a small portion of the payment until, they say, they get city council approval. It’s been about eight months now. We are faced with assuming the last payment isn’t going to be paid, or is going to be very late. So we try to adjust our hours on the project accordingly. Of course, this is easier said than done. This is always an ongoing learning curve.

There is no question that you’re going to get burned some as part of the learning curve of working in these markets—not budgeting for design changes that result from designing without a defined program, for instance. You can’t escape that, which is why it would be very wise, if you can work it out, to partner with a firm that has done work there, and also to partner with a local Korean or Chinese firm that has done work with the client.

Another critical element of being profitable overseas is to learn the tax structure of each country. In Korea, it is fairly easy. The Koreans wire dollars to our bank, and we pay our taxes here. The Chinese require months of paperwork if you want to wire dollars out of China to U.S. banks. Most owners now pay in Chinese RMB, which means we have to open an office in China. I’ve seen the 20-page documents where they want to know everything about your company, plus there is close to a 35-percent tax if you don’t do things right. And if you do succeed in doing things right, the tax on profit is about 15 percent. We recently sent a tax lawyer to Beijing to help us through this new upswing in our learning curve.

Asian A/Es are quick learners, hard workers

If you get a good local architect—and we’ve been lucky—they

are wonderful partners. First of all, they are very conscientious to

make sure that every line you draw, every intention you have is well

understood by them and covered. We will send drawings to our local colleagues,

and they will send six or seven different versions of design development

or construction document on a specifically difficult detail just to make

sure that they understood the intent. They are hungry to understand any

methodology we may have in the way we approach architecture. We also

learn from them.

Through FTP sites—and software that allows us to exchange large files and keep meticulous records of who accesses what and when—we have the proverbial 24/7 operation. When I finish at 7 p.m., I can call our associate architects in Korea or China and tell them we’ve done changes and ask them to take a look at it and get back to us tomorrow, next week, or whatever. And when I go to bed, they’re working on the project. It really goes around the clock, which can keep us for a late dinner many times. But, when it has to happen, it can.

Now,

our office works hard. But I’ve gone to some Chinese offices

after dinner and been surprised to find, at 10 o’clock, half of

the office still working. The first time I saw that, I asked what was

going on, is there a major project delivery deadline? My host said, “No,

we’ve got lots of work, so the kids stay here, they sleep on the

tables, and they have public baths where they go to relax.”

Now,

our office works hard. But I’ve gone to some Chinese offices

after dinner and been surprised to find, at 10 o’clock, half of

the office still working. The first time I saw that, I asked what was

going on, is there a major project delivery deadline? My host said, “No,

we’ve got lots of work, so the kids stay here, they sleep on the

tables, and they have public baths where they go to relax.”

We cannot survive without the local associate’s guidance on required deliverables. The governments in Korea, China, Vietnam, and Japan require considerable documentation. Our local associates actually bind them as a book and deliver them at half size to their approving authorities.

In the case of codes, the local authorities often look to us. Even though China has had building codes for a number of years, they just don’t cover the issues involved with tall and long buildings. Because of the current infusion of mega-architecture, they are willing to listen to Western approaches to public health, safety, and welfare in these buildings.

Likewise, on my first project in Korea, they didn’t have any accessibility codes. The owner and government told us to use ours, and if they liked it, they’d approve. And the owner—in this case, a very large company—used that as a marketing hook, saying they were using Western accessibility codes. The government, in turn, was very eager to agree.

Asia offers an abundance of freedom of expression

In the U.S., you really have to justify everything you do. If you do

some cutting-edge design, you have to get concurrence with community

leaders, design-review boards, university regents, or whoever the decision

makers are. In China, Korea, and Vietnam, it’s sort of a Wild

West atmosphere. They encourage you to be as noticeable as possible.

There’s also more symbolism involved in their design. In Shanghai, for instance, owners love to do dramatic things at the head of their towers. Each tower has its own; most are bad, but some are captivatingly dramatic. There is a famous tower in Shanghai that has a lotus flower cap that is gorgeously lighted and has become a symbol in the city. On the plus side, American architects do find that they have much more freedom of expression in design, and it’s wonderful, because that is what we are exporting.

Copyright 2006 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()

Francis Bulbulian is a principal with Parker Durrant International, based in Minneapolis and part of The Durrant Group, which has 12 offices nationwide.

![]()