by Andrew Brodie Smith

In the spirit of celebration and with great expectancy, members of

the AIA gathered for their Centennial Convention at the Sheraton

Park Hotel in the leafy Woodley Park neighborhood of Washington,

D.C. It was the spring of 1957, and the occasion couldn’t have

been more auspicious. Membership in the Institute had been surging

since WWII, and the construction industry was booming throughout

the U.S. Architects had plenty of work and the Institute’s

coffers were full. There was much to honor in the Institute’s

illustrious past, and the future looked bright.

AIA President Leon Chatelain read a letter to the assembled from

President Eisenhower congratulating the Institute on its 100-year

anniversary. Vice President Richard Nixon sent a telegram, too. The

Institute had gathered a group of illustrious non-architect

speakers and guests for the occasion, unrivaled since the time,

nearly 50 years earlier, when President Theodore Roosevelt made an

appearance at a ceremony honoring Augustus Saint-Gaudens held as

part of the AIA’s 1908 Convention.

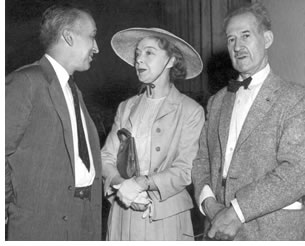

Bennet Cerf, leading literary light of New York and the publisher

of Random House, gave an uproariously funny address about the

current state of the publishing industry. Dr. Howard Mitchell,

conductor of the National Symphony Orchestra, prepared a special

program of music, “Music and Architecture in the Environment

of Man,” that the NSO performed. Other speakers included Time,

Inc.’s editor in chief Henry R. Luce and actress Lillian Gish.

David Brinkley, later to become an Honorary AIA member, was on hand

to cover the event for NBC television. The Centennial Convention

was a true celebration of The Institute in particular and American

arts in general.

UAW President

Reuther raises a red flag

UAW President

Reuther raises a red flag

Amidst the celebration walked in Walter P. Reuther, the feisty and

world-renowned president of the United Auto Workers and leading

figure in the AFL-CIO merger. He had been invited to speak to the

convention as part of a panel called “The New World of

Economics.” Reuther was to share the dais with Emerson P.

Schmidt of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and James Ashely, public

relations director for the glass company Libbey-Owens-Ford. The

panel was to be moderated by former Pepsodent

president-turned-architect Charles Luckman.

Ever the social crusader, Reuther wasn’t of the mind to throw

bouquets at the Institute in honor of its 100 years. After all,

that was not why he had been invited. His address came more in the

way of a challenge than a celebration.

“It is not a lack of economic resources,” he said,

“or a lack of technical competence. It is a lack of moral

courage and will to commit our resources to build decent

neighborhoods where people can grow up in the kind of environment,

in the kind of wholesome neighborhoods so that they can enjoy the

good life and they can develop into better and more useful citizens

… The people of the world will judge America as we need to

judge ourselves—not by our economic wealth but by the sense of

social and moral responsibility by which we are able to equate

material wealth with human values, by which we are able to

translate technical progress into human progress, into human

happiness, into human dignity.”

To the extent that the AIA had long been committed to the

improvement of the built environment for all Americans regardless

of class, Reuther was preaching to the choir. However, he

hadn’t accepted the invitation only to air his social vision

to a gathering of architects. He likely had something more specific

in mind. The year before, the UAW had run afoul of the AIA. The

union had for some time been organizing workers at the Kohler

Company—a well-known Wisconsin plumbing-fixtures firm with a

storied history of labor-relations strife.

Origins of the

controversy

Origins of the

controversy

UAW-CIO Local 833, the local union active at Kohler, got the idea

to send letters to architects around the country asking them to

boycott the company’s products in support of the striking

workers. Members of the Institute received the letters and alerted

the national office of the campaign. The AIA was an organization

that long considered itself progressive on the question of labor.

It had maintained an open and cooperative dialogue with building

and allied trades and saw the cause of labor as not inimical to the

overall health of the construction industry.

The brand new AFL-CIO headquarters on 16th Street in Washington

stood as further testament to the good relations between the

Institute and organized labor, designed as it was by Ralph Walker,

beloved former president of the Institute and the recipient of that

year’s AIA Centennial Gold Medal. But, clearly, the AIA could

not countenance the kind of interference with the architect/client

relationship that the efforts of Local 833 at Kohler

represented.

To ask an architect not to specify a particular brand of building

product would be like asking physicians not to dispense a

much-needed medication. Alarmed, AIA Executive Director Edmund

Purves and AIA President George Bain Cummings called a meeting with

Richard Gray, president of the AFL Building and Construction Trades

Department, and Emil Mazy, UAW secretary. In the meeting, the union

leaders agreed to ask Local 833 to cease its letter writing

campaign.

The story would have ended there if not for the fact that union

leaflets regarding the labor problems at the Kohler plant had

mysteriously appeared on all the chairs in the ballroom prior to

the panel presentation. Reuther denied any involvement in the

placing of the literature. Hotel management couldn’t explain

its presence either. The pamphlets were already on the chairs when

the ballroom was opened at seven in the morning. Moreover, Reuther

made a statement during his address to the Institute meant

deliberately to force the issue.

“We in the labor movement,” he said, “believe that

every child made in the image of God has the right to grow limited

only by the capacity that God gave each child to grow. I say

there’s something wrong with the basic moral fiber of a free

society that is more concerned with the condition of its plumbing

than with the adequacy of its educational system.”

“The

condition of its plumbing”

“The

condition of its plumbing”

Certainly a man of Reuther’s political stripe and

sophistication wasn’t arguing against the importance of modern

sanitation. There was only one likely interpretation: the UAW

president was taking a veiled dig at the AIA regarding its response

to the Kohler boycott efforts. The thought must have been running

through the minds of almost every architect in attendance.

The panel’s question-and-answer period was to be handled via

hand-written questions submitted from the audience. Moderator

Luckman read the fifth question: “Mr. Reuther, how does the

secondary boycott raise the moral and spiritual values that you

talk about?” Someone had taken the bait.

Reuther pounced. “I presume the reference to secondary boycott

refers to the current Kohler strike, and I am sure that all of you

in your professional activities have had some contact with this

problem.” He proceeded to methodically lay out the

union’s case against Kohler, beginning with the bloody events

of 1934 when Kohler’s company guards opened fire on striking

and rioting workers, killing 2 and wounding more than 30.

He brought up the problem of silicosis and other workers’

health problems at the factory. He mentioned the company’s

infamous intransigence, refusing to accept a proposal for

arbitration even from Wisconsin Governor Walter Kohler

Jr.—owner Herbert Kohler Sr.’s own nephew. He brought up

Kohler’s admission before the Wisconsin State Mediation Board

that the company still maintained a private arsenal of weapons

despite the tragedy of some 20 years earlier.

Reuther could barely contain his indignation: “This is a moral

question, to persuade people to not use Kohler fixtures … We

say so long as this company is going to act irresponsibly and

immorally, we are going to do everything we can to persuade people

not to use Kohler fixtures so that we can protect the economic

interest and well being of the workers who are merely asking for

their measure of economic and social justice.”

The audience applauded as Reuther finished. Letter-writing campaign

or no, the UAW president had won the day, successfully and

dramatically articulating his union’s position to a captive

ballroom filled with the most influential architects in the

country.

Civil rights

make their AIA-convention premiere

Civil rights

make their AIA-convention premiere

The labor problems at Kohler aside, Reuther’s address to the

AIA is notable for another reason. Those paying careful attention

would have heard the UAW president use the term “civil

rights”—likely the first public mention of the issue at

an AIA national convention. And in this regard, Reuther sounded a

note that would resonate for decades to come both at the Institute

and in American society as a whole.

What happened at Kohler? It took another eight years, one of the

longest strikes in UAW’s history, and among the most

protracted cases before the National Labor Relations Board, but the

UAW eventually prevailed. Kohler would recognize the union and

agreed to pay workers $3,000,000 in back pay and another $1,500,000

in restored pension rights. As to whether any of the architects in

attendance that morning during Reuther’s speech furthered the

UAW’s cause by limiting their specification of Kohler

products, that can only be a matter of conjecture.

A final note

In 1970, The AIA invited Reuther once more to address its

Convention. He was to give the prestigious Purves Memorial Lecture.

Tragically, this command performance was never to occur, as a month

before the event, Reuther and his wife were killed in a plane crash

en route to inspect the UAW’s new education center at Black

Lake, Michigan. The AIA lost one of it own aboard the downed jet

also: Oscar Stonorov, an Institute Fellow and the center’s

architect. An AIA memo memorializing the union leader said,

“many of the ideals and policies he championed came to pass

and are now accepted as part of the American Way of Life with

hardly a ripple of opposition or concern. We have lost a voice of

social concern and, yes, professional responsibility.” Upon

his death, the Board of Directors of The AIA established a

scholarship for disadvantaged students in his memory.

Copyright 2005 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page