1/2006

Build it and they will come

by Russell Boniface

Associate Editor

Once upon a time, a dedicated committee presented a proposal to Congress for a National Museum of the Building Arts. The proposal, titled “The Building Building,” outlined an institution dedicated to exploring and celebrating the built environment.

Individuals love to look at buildings, bridges, churches, and houses, believed the committee. Whatever the architectural subject matter, and whomever the audience—architects, engineers, families, and their children—it will appeal to all ages.

That

was 1978. Two years after the proposal, Congress chartered the National

Building Museum. In 2005, the National Building Museum celebrated its

25th anniversary. Since opening its doors in 1980, approximately 400,000

visitors annually have, as predicted, arrived to appreciate architecture.

That

was 1978. Two years after the proposal, Congress chartered the National

Building Museum. In 2005, the National Building Museum celebrated its

25th anniversary. Since opening its doors in 1980, approximately 400,000

visitors annually have, as predicted, arrived to appreciate architecture.

Celebrating architecture in an immense way

The large, red brick National Building Museum and its seven galleries

honor the history, present-day, and future of architecture, design,

engineering, construction, and urban planning. The museum is a private,

nonprofit institution that relies on donations and memberships. It

has more than 4,900 members.

“We are excited to have reached such an important milestone in the museum’s history,” says Executive Director Chase Rynd. “Indeed, we are indebted to our present community and our past pioneers for the success of the first 25 years. As the museum honors its past and also looks toward the future, we invite the local and the national community to celebrate with us.”

In the last 25 years, more than 150 exhibitions, lectures, and symposiums have attracted visitors and building professionals alike. Exhibit topics have ranged from buildings to bridges and are presented through collections of photographs, blueprint drawings, wall displays, tours, and films. While the exhibitions have engaged and informed the public through the years, the museum has also become a forum for professionals exchanging ideas and information about topical issues such as managing suburban growth, preserving landmarks and communities, sustainability, affordable housing, and revitalizing urban centers. Leading architects and designers, including 14 AIA Gold Medalists and 4 Pritzker Prize winners, have addressed crowds at the museum or participated in exhibitions.

“Just

25 years after its inception, the National Building Museum is now the

premier forum for the exchange of ideas about architecture, design, and

construction,” says Carolyn Schwenker Brody, current

chair of the Board of Trustees. “As we look to the future, we plan

to play an active role in framing the debate about the shape of our environment.”

“Just

25 years after its inception, the National Building Museum is now the

premier forum for the exchange of ideas about architecture, design, and

construction,” says Carolyn Schwenker Brody, current

chair of the Board of Trustees. “As we look to the future, we plan

to play an active role in framing the debate about the shape of our environment.”

Interactive exhibits have always been crowd pleasers. For example, visitors

currently can learn how a truss provides strength and longevity, and

then test different building materials and work together to construct

an arch; or, they can learn about bridge types and solve a community’s

transportation problem by trying their hand at bridge design. Some exhibits

are now available online in the form of virtual tours, with 600,000 “virtual

visitors” in 2004. Without leaving your chair, you can currently

go to www.nbm.org and read about a proposed portable skyscraper at “Building

America”; or go to “Liquid Stone” to learn about translucent

concrete. The museum also offers education programs that include curricula

for school children.

The National Building Museum’s permanent collections contain approximately

40,000 photographic images, 68,000 architectural prints and drawings,

and 2,100 objects, including building samples and architectural fragments.

Great open spaces

The museum building is inspiring unto itself. Designed in 1881 by General

Montgomery C. Meigs, a civil engineer and quartermaster general in

the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the building was completed in 1887

and was loosely modeled on Rome’s three-story Italian Renaissance

Farnese Palace, which it in fact exceeded in scale. Meigs designed

an enormous 75-foot-tall rectangle, 400x200 feet. The building was

Meigs’ last architectural work and the one of which he was most proud.

The building was designed and built to be the Pension Bureau, established

to care for Union Civil War veterans. Many other government agencies

subsequently occupied it as well. According to Meigs’ precise records,

it cost $886,614. It received National Historic Landmark status in

1985.

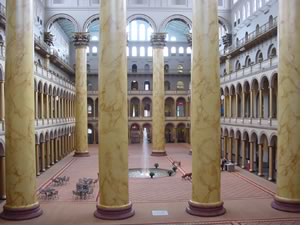

The

building is made from 15.5 million red bricks, stretches one city block,

and has a two-acre roof that reaches 159 feet at its highest point. Inside,

the three adjoining courts that compose the Great Hall dominate the museum

with a 19th-century setting. The Great Hall measures 316x116 feet—roughly

the size of a football field—and has eight,

75-foot Corinthian columns, the tallest interior columns in the world.

Each column is made from 55,000 bricks, has an 8-foot circumference,

and is finished in scagliola. The Hall interior is painted in period

colors, and its operable clerestory windows, vents, and open archways—formed

from 72 terra cotta and iron columns on each of the first two floors—allow

it to function as a “reservoir of light and air.” The building

was designed to provide natural air-conditioning and light for its employees.

A natural ventilation system features air vents in the exterior walls

of the building. Hot air escapes through the skylights in the roof thereby

drawing fresh air in through the exterior-wall openings. Present-day

visitors can still spot three openings in the brickwork under each of

the building's 240+ windows. In the center of the Great Hall is a large

circular fountain, 28 feet in diameter, with a single jet of water shooting

toward the ceiling.

The

building is made from 15.5 million red bricks, stretches one city block,

and has a two-acre roof that reaches 159 feet at its highest point. Inside,

the three adjoining courts that compose the Great Hall dominate the museum

with a 19th-century setting. The Great Hall measures 316x116 feet—roughly

the size of a football field—and has eight,

75-foot Corinthian columns, the tallest interior columns in the world.

Each column is made from 55,000 bricks, has an 8-foot circumference,

and is finished in scagliola. The Hall interior is painted in period

colors, and its operable clerestory windows, vents, and open archways—formed

from 72 terra cotta and iron columns on each of the first two floors—allow

it to function as a “reservoir of light and air.” The building

was designed to provide natural air-conditioning and light for its employees.

A natural ventilation system features air vents in the exterior walls

of the building. Hot air escapes through the skylights in the roof thereby

drawing fresh air in through the exterior-wall openings. Present-day

visitors can still spot three openings in the brickwork under each of

the building's 240+ windows. In the center of the Great Hall is a large

circular fountain, 28 feet in diameter, with a single jet of water shooting

toward the ceiling.

Seven large, interconnected galleries make up the museum. With minimal display walls and high-vaulted ceilings, visitors can easily traverse through the open spaces of the entire museum. In 1984, 244 busts by acclaimed Washington sculptor Gretta Bader were added to sit 118 feet in the air in the Great Hall, encircling the Hall’s center court. The remarkable busts are in eight different models: bricklayer, architect, construction worker, landscape architect, financier, engineer, craftsman, and developer. Bare bulbs line the first two levels of the museum to give the illusion of gas lighting.

The Great Hall has attracted many presidential inaugural balls and gala events—beginning in 1893 for Grover Cleveland—but the tradition faded after William Howard Taft’s 1909 inaugural ball. The General Accounting Office and other subsequent agencies partitioned the Grand Hall into cubicles that prevented its use for public functions. In 1973, during Richard Nixon’s presidency, the cubicles were finally removed. The Great Hall was once again the place to be for the inaugural ball and has been the site ever since. Recently, President and Mrs. Bush attended the National Building Museum for a holiday benefit for the National Children’s Medical Center. (A virtual tour of the Great Hall is available on the Museum’s web site at www.nbm.org.)

On

the exterior of the building, a red terra-cotta frieze wraps the entire

1,200-foot perimeter and depicts a parade of Civil War military units.

The frieze was designed by Bohemian-born sculptor Caspar Buberl and meant

to reflect the cause for which Civil War veterans had fought.

On

the exterior of the building, a red terra-cotta frieze wraps the entire

1,200-foot perimeter and depicts a parade of Civil War military units.

The frieze was designed by Bohemian-born sculptor Caspar Buberl and meant

to reflect the cause for which Civil War veterans had fought.

Cityscapes Revealed

In celebration of its 25th year, the National Building Museum is hosting

a 2,500-square-foot exhibition titled “Cityscapes Revealed: Highlights

from the Collection” that explores the history of America’s urban

architecture. “Cityscapes Revealed,” a three-gallery exhibit,

opened on December 3 and is long-term. It is a first-time viewing of

a collection that started as far back as 1977 and was ongoing but never

displayed to the public. More than 100,000 shop drawings, blueprints,

photographs, and architectural elements are on display now for visitors

to see as they take a walking tour through a 20th-century “cityscape.” Building

fragments of urban structures—such as skyscrapers, row houses,

mansions, and storefronts—offer building details that a person

might not otherwise notice from ground level, such as a Classic copper

acroterion from a 1900 roofline, brought down from the skies for visitors

to view up close.

Smaller architectural elements, such as brick bond patterns, watercolor

construction designs, and terra-cotta façades from early skyscrapers

make up a large part of the exhibit. Details also highlight the skills

of designers, craftspeople, and contractors of various periods. However, “Cityscapes

Revealed” is anchored by larger, finely crafted works that include

a copper dormer from the Carnegie Mansion on Millionaires’ Row

in Manhattan, an Art Deco terra-cotta window surround from the lost S.H.

Kress & Co. five-and-dime in Phoenix, and a sheet-metal section of

Salt Lake City’s legendary Z.C.M.I. department store.

Smaller architectural elements, such as brick bond patterns, watercolor

construction designs, and terra-cotta façades from early skyscrapers

make up a large part of the exhibit. Details also highlight the skills

of designers, craftspeople, and contractors of various periods. However, “Cityscapes

Revealed” is anchored by larger, finely crafted works that include

a copper dormer from the Carnegie Mansion on Millionaires’ Row

in Manhattan, an Art Deco terra-cotta window surround from the lost S.H.

Kress & Co. five-and-dime in Phoenix, and a sheet-metal section of

Salt Lake City’s legendary Z.C.M.I. department store.

“The collection is an excellent introduction to the museum and its mission to celebrate American achievements in the building arts,” says Chrysanthe B. Broikos, architectural historian and curator of “Cityscapes Revealed.”

The exhibit is broken down into specific collections. The Northwestern

Terra Cotta Company Collection showcases an impressive 50,000 original

ink-on-linen drawings and architectural elements. (Terra cotta emerged

as the building material of choice after the Chicago fire of 1871.) Examples

include a terra-cotta rosette cast from the cornice of the Building Museum

(then the U.S. Pension Building), a sculpted shell-shaped acroteria that

ornamented a building’s roofline from 1914, and a 1908 shop drawing

that details one of the many majestic spread eagles that ornament Pittsburgh’s

Allegheny County Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Hall.

The exhibit is broken down into specific collections. The Northwestern

Terra Cotta Company Collection showcases an impressive 50,000 original

ink-on-linen drawings and architectural elements. (Terra cotta emerged

as the building material of choice after the Chicago fire of 1871.) Examples

include a terra-cotta rosette cast from the cornice of the Building Museum

(then the U.S. Pension Building), a sculpted shell-shaped acroteria that

ornamented a building’s roofline from 1914, and a 1908 shop drawing

that details one of the many majestic spread eagles that ornament Pittsburgh’s

Allegheny County Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Hall.

The Kress Collection displays 13,000 architectural drawings and vintage photographs—also paired with original architectural elements, such as an original painted-plaster sconce from the S. H. Kress & Co. chain of five-and-dimes, whose store’s designs ranged from Beaux Arts to Greek Revival. The collection of the James Stewart Construction Company, whose clients included The Pennsylvania Railroad, Standard Oil, U.S. Steel, General Electric, and the B & O Terminal Warehouse in Baltimore, has more than 100 leather-bound photograph albums from projects undertaken between 1904 and 1949, each containing 30-80 prints documenting a construction project from excavation to completion.

The Wurts Brothers Photography Collection showcases the work of one

of the first firms to specialize in architectural photography. Photographs

document buildings’ architectural styles and building materials

of early 20th-century America. Photographs in the exhibition focus on

office buildings and notably include a 1953 picture of the former headquarters

of the Aluminum Company of America (ALCOA) in Pittsburgh, the first skyscraper

completely clad in aluminum and an icon of post-War architecture. The

American Brick Collection includes nearly 2,000 bricks from brickyards

across the country and documents a wide variety of decorative styles

from both the 19th and 20th centuries. An interactive station allows

visitors to try their hand at different bonding patterns. The Ernest

L. Brothers Interior Design Collection reveals the tastes and styles

of the American elite in the mid-20th century with drawings, watercolors,

fabric samples, and furniture hardware. An example is a Louis XVI-inspired

canopy bed, circa 1950.

The Wurts Brothers Photography Collection showcases the work of one

of the first firms to specialize in architectural photography. Photographs

document buildings’ architectural styles and building materials

of early 20th-century America. Photographs in the exhibition focus on

office buildings and notably include a 1953 picture of the former headquarters

of the Aluminum Company of America (ALCOA) in Pittsburgh, the first skyscraper

completely clad in aluminum and an icon of post-War architecture. The

American Brick Collection includes nearly 2,000 bricks from brickyards

across the country and documents a wide variety of decorative styles

from both the 19th and 20th centuries. An interactive station allows

visitors to try their hand at different bonding patterns. The Ernest

L. Brothers Interior Design Collection reveals the tastes and styles

of the American elite in the mid-20th century with drawings, watercolors,

fabric samples, and furniture hardware. An example is a Louis XVI-inspired

canopy bed, circa 1950.

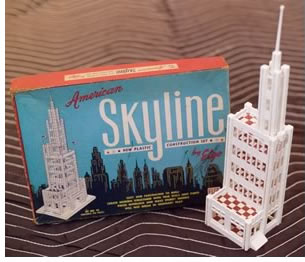

But

wait . . . there’s even more to see. Since 1910, the Turner

Construction Company, one of the largest U.S. contractors, has commissioned

an artist’s rendering of the firm’s annual achievements.

The Turner City Collection juxtaposes these drawings to make Turner City,

an imaginary metropolis that highlights how architectural tastes, building

types, and construction technologies have changed over time. And the

Pension Building Collection tells the story of the design and construction

of the museum’s terra-cotta elements. Don’t forget to browse

the collection of vintage toy building sets, where you will see, for

example, Elgo Plastics’ 1956 “American Skyline” construction

set that captures the look of white-glazed terra-cotta skyscrapers, such

as the Wrigley Building.

But

wait . . . there’s even more to see. Since 1910, the Turner

Construction Company, one of the largest U.S. contractors, has commissioned

an artist’s rendering of the firm’s annual achievements.

The Turner City Collection juxtaposes these drawings to make Turner City,

an imaginary metropolis that highlights how architectural tastes, building

types, and construction technologies have changed over time. And the

Pension Building Collection tells the story of the design and construction

of the museum’s terra-cotta elements. Don’t forget to browse

the collection of vintage toy building sets, where you will see, for

example, Elgo Plastics’ 1956 “American Skyline” construction

set that captures the look of white-glazed terra-cotta skyscrapers, such

as the Wrigley Building.

Looking ahead

In 2006, the museum will present a groundbreaking exhibition on sustainability

in residential architecture and design. “The Green House: New

Directions in Sustainable Architecture and Design” will open

in May and examine new developments in green residential design, technology,

and products. Opening in June is “Prairie Skyscraper: Frank Lloyd

Wright’s Price Tower,” which will examine the evolution

of Wright’s concept of the modern office building. Also in the

planning stages are exhibitions on America’s World Fairs of the

1930s, an in-depth show about the American home, and a retrospective

on the works of Eero Saarinen. In 2007, the Museum will participate

in a citywide Shakespeare Festival, investigating how architecture

comes together with theater. Says Executive Director Rynd: “Based

on the first 25 years of the National Building Museum, the sky is the

limit as to where this institution can go.”

Copyright 2006 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()

Visit the National Building

Museum’s Web site. ![]()

Location. The National Building Museum is located in Northwest Washington, D.C., on F Street between 4th and 5th streets and is adjacent to the Judiciary Square Red Line Metro stop. Phone: 202-272-2448. “Cityscapes Revealed” is on view in the first-floor galleries.

Admission. Admission to the general public is free. (A donation of $5 per person is suggested). Hours are Monday-Saturday, 10 a.m.–5 p.m., and Sunday, 11 a.m.–5 p.m.

Learning units. The National Building Museum is an AIA/Continuing Education System Registered Provider. Learning units can be earned by participating in the museum's programs. Registration is required for all lectures and symposia. Online registration for certain programs is available.

Did you know . . .

• The AIA 2006 Gold Medal will be awarded to Antoine Predock, FAIA,

at the National Building Museum on February 10 at the American Architectural

Foundation/AIA Accent on Architecture Gala.

• Having a party? You can rent the Great Hall. Rental to outside organizations

raised more than $1.2 million for the museum in 2004.

• The museum is the biggest building ever built of load-bearing brick

masonry.

• When built, the building was derided as "Meigs old red barn" and

criticized for not fitting in with Washington's Neoclassical architecture.

• The building barely escaped demolition several times.

• A presidential seal in the building’s floor is said to be

the only one outside the White House.

• The finest of the Kress stores were called “superstores.”

![]()