11/2005

The morning of November 12, the third day of the LRCC, centered on tools and techniques and lessons learned that the people of the Gulf Coast region can consider for rebuilding communities, from broad-brush planning techniques to zoning laws and building codes. Each of the six speakers also provided the participants with a set of principles they could use in the rebuilding.

Planning and designing great neighborhoods

Planning and designing great neighborhoods

David Dixon, FAIA, Goody Clancy, told participants that the process should

be about “learning to love neighborhoods again,” not just

about building houses. “You can add your visions to the good

things of the past. This is about restoring, not rebuilding,” he

added.

Most of the neighborhoods we have built over the past few decades are “one size fits all,” where the population is homogenous. “That era is over!” Dixon declared. “The housing market of 50 years has collapsed. People of all ages now spend about the same amount of money on housing, as opposed to the traditional bell-curve of housing spending that has the middle-aged population doing the lion’s share of the spending. “So we now need all kinds of housing,” Dixon said.

Signs of the rapidly changing market include the fact that condos are now more expensive than single-family housing. Dixon also said that there are signs that people are really sick of commuting and want to live near transit. “Neighborhoods are getting more diverse as different kinds of people seek the housing options they want, and great neighborhoods attract the people who attract the investors,” Dixon explained.

Dixon offered the following principles:

- Create communities, not neighborhoods. Build neighborhoods that have “great, walkable centers” as a civic framework.

- Accommodate diversity in race, age, and household types, with public spaces and social services that invite and draw.

- Create the right densities; that is, enough density to support diverse housing, services, libraries, and parks. Higher densities can support low-income housing. You need 1,500-2,000 housing units to support one block of walkable main street, he said.

Integrating the elements into urban design

Integrating the elements into urban design

Michael Willis, FAIA, Michael Willis Architects, San Francisco, who grew

up in St. Louis, another great Mississippi River city, offered his

advice in the form of four overarching principles:

1. Responsibility: “Collectively, we have a responsibility to rebuild,” Willis declared. He told stories of how he as a child was one of the first residents of St. Louis’ Pruitt-Igoe complex, which was supposed to be “the salvation of public housing.” As an architecture student in 1972, he watched the complex dynamited as testament to its unfitness. The second personal experience Willis recounted was of being in San Francisco during the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. These experiences fueled his desire to rebuild communities. “Do we just put things back, or do we rebuild better?” he asked.

2. Collaboration: “Don’t pass over collaboration as self-evident,” Willis advised, “I can see in the room that it is not. Everyone must be at the table.” He explained that you get a richer, better, truer result from this admittedly messy process. “You never know where that spark of wisdom is going to come from—we’re not smart enough to exclude anyone,” he said.

3. Permission: “You should have permission to look beyond this disaster—plan at the broadest scale possible,” Willis said. He gave the group a symbolic “permission slip.” “Allow yourself the opportunity to look beyond your job description,” he advised. “Improvise about money: It’s one ingredient.”

4. Memory: “Picture the river that connects your hometown with mine,” Willis said. It depends on the storytellers who cherish the memory of place to help the professionals get it right. “New Orleans is the story, and you are the storytellers,” he concluded.

Suburban and rural smart growth

Suburban and rural smart growth

Jerry Weitz, PhD, a city planner from Alpharetta, Ga., stressed the need

for an intergovernmental community-building framework: He urged the

participants to establish or reinvent regional entities to provide

technical assistance and allocate resources, as well as bring in the

nonprofit organizations and leverage volunteers.

Weitz encouraged participants to strive for:

- Smart growth that recognizes that scattered pattern of low density is unwise

- Safe growth, which mitigates impacts from unsafe development practices

- Fair growth, which emphasizes social equity.

“We cannot ignore concentrated poverty,” he said. In terms of planning and tools, Weitz offered eight tenets:

- Stay away from unsafe areas and turn them into assets.

- Bring back the neighborhood school and review the neighborhood unit planning concept.

- Plan sports and other assembly facilities for other uses.

- Achieve job-housing balances that mix uses that bring homes and workplaces together.

- Provide incentives for or require mixed-income housing developments.

- Retrofit suburban subdivisions with better connectivity and access to multiple modes of transportation.

- Modify local zoning codes to include form-based codes and other approaches that promote traditional neighborhoods with character.

- In rural areas, cluster residential development in conservation subdivisions to protect open spaces.

Weitz concluded with three principles:

- Pursue new forms of intergovernmental coordination.

- Pursue a comprehensive approach to rebuilding.

- Implement principles and tools for building quality communities.

Balancing individual and community rights

Balancing individual and community rights

Edward Ziegler, University of Denver professor of law and cofounder of

the Rocky Mountain Land Use Institute, offered some background principles

of constitutional law as they pertain to the rebuilding, including:

- The police power to regulate and restrict the use and development of land

- Eminent domain, which is the power of government to take private property, with just compensation, and put it to public use.

“You really need to have political will at the local level to use these tools,” he explained. “There’s very little private property rights have to do with public planning; the jurisdiction has a great deal of power and Louisiana law is not that different from other states in these areas,” Ziegler said. “The important thing is to use these tools wisely. The rubber meets the road at the local parish level.”

Ziegler also offered the following thoughts:

- Temporary restrictions on land development may be appropriate in some areas pending formulation of planning principles.

- Private property rights don’t include development or use that poses substantial risk of harm to the public HSW.

- Police power can be used in creative and positive ways. As an example, affordable housing can be created through incentive and inclusionary zoning provisions and by public and private partnerships, sometimes supplemented with eminent domain. “Zoning can really build communities. Tools are available—you have to have the political will,” Ziegler reiterated.

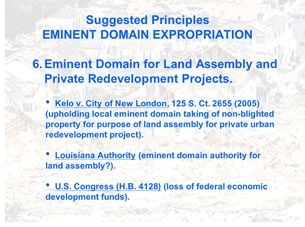

- Power of eminent domain may be useful.

- The state should consider mandatory mediation as a precondition to jury-trial “just compensation” in eminent domain litigation.

- Eminent domain may be necessary and appropriate for the purpose of land assembly to assist private development projects that implement public projects. He advised participants to follow a bill currently before congress, HB 4128, on this subject.

- The rebuilding needs transparent, open plans and project review/approval processes.

“As you go forward, you won’t be rebuilding alone,” he assured the participants.

Use the zoning code to community advantage

Use the zoning code to community advantage

Craig Richardson, a city planner and attorney who serves as vice president

of the Chapel Hill, N.C., planning firm Clarion Associates, spoke of

the zoning code as “a tool for building a better future.” He

developed his principles for rebuilding in three broad areas:

- The zoning code is a regulatory tool to support community rebuilding; it is not a panacea. It emanates from policy powers for land use, development, and quality of development, and you can use it to achieve the kinds of development you want. Richardson warned the participants that zoning codes are “subject to political change and lore,” and must be administered in a legally acceptable way.

- Understand what your zoning code can and cannot best help you achieve, Richardson advised. Set goals first to use the zoning codes to best advantage. For instance, you can develop standards to make redevelopment compatible with context and provide incentives for developing hazard mitigation techniques. Conversely, you can create zoning codes that discourage new public facilities in hazardous areas. Reduced to its simplest, you can “make appropriate development easy and inappropriate development hard,” Richardson said.

- Be bold—create opportunities to build a better community future, Richardson advised. Goals could include community-wide benefits, such as a floodplain retrofit plan connecting the community to green space. “You have tremendous opportunities to rebuild your communities as you want them,” he concluded.

Toward a statewide code

Toward a statewide code

Henry Green, executive director of the Bureau of Fire Codes and Safety

in Michigan and president of the International Codes Council (ICC),

who also has served as president of the National Institute of Building

Sciences, said that he believes that the ICC and the visions being

defined at the conference are well aligned. Green explained that the

ICC supports the adoption of a statewide building code that allows

public input. A statewide code will protect the public and reduce the

resources that individual jurisdictions have to put into their own

codes. “There’s nothing wrong at looking at national standards

in developing your own statewide code,” he said.

The ICC is enforced in 45 states, and the ICC residential code has been adopted by 27 states and jurisdictions that include 13 jurisdictions in Louisiana. Green urged participants to recognize that codes establish minimum standards for protection, and safe buildings must be designed and constructed. “It must be a collaborative effort of design, building, and regulatory communities,” he explained.

Green also suggested that participants explore how codes can reduce recovery costs. For instance, he said, builders in Florida built fast and cheap before 1992’s Hurricane Andrew hit. After Andrew, Florida adopted a statewide code (based on the model International Building Code), and, consequently, newer buildings withstood the 2004 barrage of hurricanes much better than did their pre-Andrew counterparts.“We need to take a look at the available lessons learned,” he said. Green also announced that the ICC is going to establish an office in Louisiana to provide assistance to local code enforcement.

The four principles with which Green concluded are:

- Adoption of comprehensive codes saves lives.

- Enforcement of comprehensive codes protects property.

- Comprehensive codes are minimum standards.

- Never settle for the minimum.

Copyright 2005 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()

|

||

|

||