10/2005

One scenario for expanding architecture practice

by Jonathan Cohen, FAIA

Compared to other large industries, the building industry is highly fragmented, with most projects undertaken by temporary, project-based organizations consisting of many small firms—architect, engineer, contractor. Communication and the exchange of data among these firms are crucial to the success of any project. Unfortunately, the fractured nature of the building industry is reflected in its information systems.

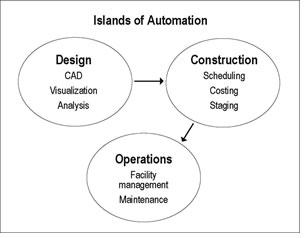

![]() In many ways, information technology has made communication within this

extended enterprise worse rather than better. Incompatible systems used

by different disciplines create artificial barriers that hadn’t

existed in the analog world. Within the domains of design, construction,

and building operations, computers have been applied to automating specific

tasks rather than addressing the overall building process. The design

team may use computer-aided design to produce the drawings required for

bidding and construction, but these digital work products are not necessarily

useful for the tasks performed by the contractor: costing and scheduling.

The proprietary file formats used by CAD programs can’t be read

by project management software.

In many ways, information technology has made communication within this

extended enterprise worse rather than better. Incompatible systems used

by different disciplines create artificial barriers that hadn’t

existed in the analog world. Within the domains of design, construction,

and building operations, computers have been applied to automating specific

tasks rather than addressing the overall building process. The design

team may use computer-aided design to produce the drawings required for

bidding and construction, but these digital work products are not necessarily

useful for the tasks performed by the contractor: costing and scheduling.

The proprietary file formats used by CAD programs can’t be read

by project management software.

As a result, much exchange of information is still reduced to paper, even when the work is produced on a computer. Whenever these information handoffs occur, the opportunity for delay and error is increased and additional time and effort are needlessly expended in reentering data into new systems. The building process would be much better served if the entire chain of information from design to construction to operations could remain in one seamless digital format.

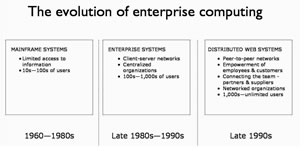

The

emergence of the Internet in the 1990s offered the possibility of connecting

the project team over a network. Networked computing presents the opportunity

to integrate information from many sources and then redistribute it to

the points of execution where it is needed. Now, the inability of software

programs to talk to each other becomes an acute liability. Just as a

new platform for exchanging digital information cheaply and securely

became available, the building industry discovered that it didn’t

have a common digital language with which to communicate.

The

emergence of the Internet in the 1990s offered the possibility of connecting

the project team over a network. Networked computing presents the opportunity

to integrate information from many sources and then redistribute it to

the points of execution where it is needed. Now, the inability of software

programs to talk to each other becomes an acute liability. Just as a

new platform for exchanging digital information cheaply and securely

became available, the building industry discovered that it didn’t

have a common digital language with which to communicate.

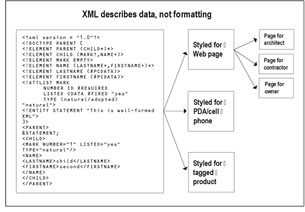

The shared project model

Data exchange standards such as XML and IFCs, combined with parametric

3-D modeling and the Internet, form the basis of a shared intelligent

building model, which could replace individual paper documents with

a single knowledge base describing an entire project. Participants

have real-time access to the model throughout the life of the project,

in turns contributing their own knowledge and using information contributed

by others. Each discipline composing a project team continues to use

specialized tools for performing its own aspect of the work, but these

tools would have the ability to draw from and contribute to a common

pool of information within an intelligent, comprehensive, information

system.

Objects within a building model carry with them dimensional data, as

CAD objects do, but also specifications, code and performance data, cost,

and information related to construction means, methods, and scheduling.

A steel beam object, for example would be drawn first architecturally, with its physical characteristics; second, structurally, with its load-bearing

properties; third, as a cost item; fourth, as a scheduled

process of

fabrication and delivery; and so on. An architect draws and models, an

engineer calculates, and a construction manager schedules, all using

information from a common project database that is accessible over a

network. Architects would contribute the physical design attributes of

a building to the larger computer representation of the building as both

an object and a process. The shared project model becomes almost a living

organism that can be accessed asynchronously by its many contributors.

Information is now available in context-specific form, rather than locked

in paper documents. Teams could have multiple “live versions” of

a project available simultaneously to fully support design collaboration.

Objects within a building model carry with them dimensional data, as

CAD objects do, but also specifications, code and performance data, cost,

and information related to construction means, methods, and scheduling.

A steel beam object, for example would be drawn first architecturally, with its physical characteristics; second, structurally, with its load-bearing

properties; third, as a cost item; fourth, as a scheduled

process of

fabrication and delivery; and so on. An architect draws and models, an

engineer calculates, and a construction manager schedules, all using

information from a common project database that is accessible over a

network. Architects would contribute the physical design attributes of

a building to the larger computer representation of the building as both

an object and a process. The shared project model becomes almost a living

organism that can be accessed asynchronously by its many contributors.

Information is now available in context-specific form, rather than locked

in paper documents. Teams could have multiple “live versions” of

a project available simultaneously to fully support design collaboration.

This kind of team-shared, Internet-accessible, single-model approach is already in wide use in the aerospace and automobile industries where it is known by the term product lifecycle integration.

Implications for the building industry

Implications for the building industry

The shared building model and the Internet offer the prospect of significant

productivity and efficiency improvement in the building industry—but

only if accompanied by significant process reform. At present no one—owner,

designer, or builder—takes the enterprise-level view of the entire

building process, and therein lies the historic opportunity for the

architectural profession.

Industries such as aerospace and auto manufacturing, shipbuilding, and process plant engineering have used enterprise-wide information technology to change fundamentally their ways of doing business. Product lifecycle integration has enabled design, production, and operations to be informed by each other in a kind of feedback loop. Results have included:

- Shorter product cycle time from concept to market

- Less waste with lean processes

- More choice for the consumer, with mass customization

- Higher quality at lower cost.

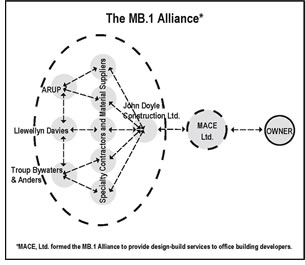

At the same time, Internet-based communication technology has enabled decentralization of organizations by making information accessible to geographically distributed work teams and supply chains. Companies such as Nike demonstrate how large enterprises can successfully outsource all production while concentrating on design, marketing, and coordination. The trend toward decentralization and outsourcing suggests that there may be new ways of organizing work that would improve efficiency in the building industry without changing its traditional reliance on small firms. By making external communication cheap and secure, the Internet changes the equation, offering the possibility of connecting the various players in a building project within networked alliances.

Networks of independent but tightly integrated firms, each contributing

to a cooperative process and supported by enhanced communication, may

be a better fit to the AEC industry than either the fragmented design-bid-build

system or the “shotgun wedding” of design-build. Flexible

alliances of specialized firms, which come together for projects, disband,

and then reform, can be highly effective if supported by an ability to

capture, store, and share knowledge and standards. Each member of the

networked alliance contributes its expertise, which adds to an ever-expanding

knowledge base to the benefit of all.

Networks of independent but tightly integrated firms, each contributing

to a cooperative process and supported by enhanced communication, may

be a better fit to the AEC industry than either the fragmented design-bid-build

system or the “shotgun wedding” of design-build. Flexible

alliances of specialized firms, which come together for projects, disband,

and then reform, can be highly effective if supported by an ability to

capture, store, and share knowledge and standards. Each member of the

networked alliance contributes its expertise, which adds to an ever-expanding

knowledge base to the benefit of all.

Who will take charge of this new, technology-supported design and building process? Clearly, the one who controls the project information will be at the center of the building team. This “project information architect” may combine characteristics now associated with architect, quantity surveyor, process engineer, and construction manager. The duties of this new kind of architect would encompass a comprehensive overview of projects throughout a process that extends from site selection and programming through the entire lifecycle of buildings.

The project information architect is the:

- Designer, not just of buildings but of the building process

- Keeper of knowledge and rules—the one who selects, filters, classifies, and maintains information within the project team and from project to project

- Maintainer of standards and quality assurance

- Builder of a community of interest around each project.

The project information architect would be at the center of flexible, net-worked alliances, temporary groupings of physically dispersed, independent companies. Such organizations are founded on trust—a willingness of participants to share goals, risks, and rewards.

Highly successful models of networked organizations have existed for many years. Movie production in Hollywood is one example. Until the 1950s, movies were made by a few vertically integrated large studios that controlled every aspect of production, distribution, and display of films. When this system collapsed under antitrust pressure, movie production shifted to project-based teams assembled to make a single film. The studios continued to control financing, marketing, and distribution, but film production became a project-based virtual enterprise. The transformation took place in just a few years.

The culture of networked organizations is based on cooperation and trust rather than hierarchical command and control. Individual small businesses are free to innovate, and these innovations are diffused throughout the enterprise. By allowing small companies to concentrate on what they do best, networked organizations foster innovation and responsiveness to customer requirements. In this environment, standards—accepted ways of doing things—become ever more important, enabling specialists who have never worked together to quickly become productive with each other in the same way that makeshift surgical teams of doctors and nurses are able to work effectively in emergencies, using well-defined protocols and procedures.

Although flexible alliances seem a perfect fit for the building industry, there are a number of deeply ingrained cultural impediments that will have to be overcome for this form of project delivery to gain acceptance. At present, no one “owns” the whole building process. The traditional insularity of the design professions from the construction process mitigates against an industry-wide focus on the customer and product. Indeed, there are few incentives for designers and builders to innovate, and sometimes there are severe risks in doing so. Risk and reward are not equitably shared among designer, builder, and owner. There is also the widely held belief that the building industry is unique, so little can be learned from other industries. Finally, legal and insurance boundaries have been so tightly drawn that they inhibit experimentation in process delivery models.

Opportunities and choices

Information technology now presents an historic opportunity for process

reform in the building industry. Will architects step up and lead or

let the opportunity pass? This is the question that the profession

must answer within the next few years.

Copyright 2005 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()

|

||

A version of this article appears in The Architect’s Handbook of Professional Practice, 2004 Update, Joseph A. Demkin, AIA, editor (John Wiley & Sons, 2004). If you have questions about what the AIA is doing about BIM, integrated practice, interoperability, or other related topics, please contact Markku Allison, AIA, 202-626-7487 or changeisnow@aia.org.

|

||