10/2005

Visionary city planner led Philadelphia’s renaissance

Edmund

Norwood Bacon, FAIA, noted director of the Philadelphia City Planning

Commission from 1949 to 1970, died in his home on October 14. Equally

described as “irascible” and “brilliant,” Bacon

dedicated his professional career to making the City of Brotherly Love

more beautiful and livable. He once called Philadelphia “the worst,

most backward, stupid city that I ever heard of,” but also said,

well before he was given responsibility for planning the city, that he

would “devote my life’s blood to making Philadelphia as good

as I could.”

Edmund

Norwood Bacon, FAIA, noted director of the Philadelphia City Planning

Commission from 1949 to 1970, died in his home on October 14. Equally

described as “irascible” and “brilliant,” Bacon

dedicated his professional career to making the City of Brotherly Love

more beautiful and livable. He once called Philadelphia “the worst,

most backward, stupid city that I ever heard of,” but also said,

well before he was given responsibility for planning the city, that he

would “devote my life’s blood to making Philadelphia as good

as I could.”

Born in Philadelphia on May 2, 1910 to an old Quaker family, Bacon had a profound love for his city and a great respect for its historical significance. After graduating with a degree in architecture from Cornell University in 1932, he headed to Europe, then China. He spent a year working for an American architect in Shanghai, where he learned that “city planning is about movement through space, an architectural sequence of sensors and stimuli, up and down, light and dark, color and rhythm.”

After returning to the U.S., Bacon studied under Eliel Saarinen at Cranbrook and worked as an urban planner in Flint, Mich., before returning to Philadelphia in 1940. During World War II, Bacon served in the U.S. Navy. In 1947, he became director of the Philadelphia Housing Association, where he co-designed the Better Philadelphia exhibition. Later that year, he joined the planning commission and became its executive director in 1949.

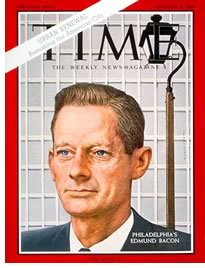

A model of renewal

Under Bacon’s watchful eye, Philadelphia underwent an urban renaissance

and became a model of renewal for other American cities. During his 21-year

tenure as executive director, he oversaw the development of Society Hill,

Independence Mall, Penn Center, Penn’s Landing, Market East, the

Far Northeast, and University City. His office was considered such a

model of effective city planning that both Time and Life magazines featured

him on their covers during the 1960s. His 1967 book, The

Design of Cities, is still used in schools of architecture and urban planning today. In

awarding him its 1971 Distinguished Service Award, the American Institute

of Planners called him “largely responsible for the rebirth of

Philadelphia as a vital city.”

Although his imprint on Philadelphia is undeniable, not all of his planned

projects were fulfilled. Bacon proposed a “Crosstown Expressway” linking

the Schuylkill Expressway (I-76) to the Delaware Expressway (I-95) that

would have severely depressed property values in the South Street corridor.

The plan was abandoned. In addition, at one time, he supported the destruction

of City Hall (all but the tower). In later years, Bacon admitted that

both projects would’ve been “terrible mistakes.”

Although his imprint on Philadelphia is undeniable, not all of his planned

projects were fulfilled. Bacon proposed a “Crosstown Expressway” linking

the Schuylkill Expressway (I-76) to the Delaware Expressway (I-95) that

would have severely depressed property values in the South Street corridor.

The plan was abandoned. In addition, at one time, he supported the destruction

of City Hall (all but the tower). In later years, Bacon admitted that

both projects would’ve been “terrible mistakes.”

Bacon believed that “Great cities are not great because of individual buildings. They’re great because of the way things fit together.” His emphasis on context and setting as opposed to individual buildings often found him at odds with the architect community. In fact, when planning Penn Center, he was rebuked by the Philadelphia chapter of the AIA for “presum[ing] to make a plan where there was no client and no program.”

Continually active

Throughout his life and career, he believed that no building in the city

should top the 491-foot height of City Hall and its statue of founder

William Penn. Developer Willard Rouse was the first to exceed the unwritten

height restriction when, in 1984, he built Liberty Place towers. Bacon

argued that a “gentleman’s agreement” bound architects

to honor the height restriction. He sent a letter to the editor of

the Philadelphia Enquirer, declaring that those who attempted to build

above 491 feet had to ask themselves, “Are you a gentleman?” Since

that time, numerous other buildings have likewise exceeded the height

of City Hall.

After retiring from civil service in 1970, Bacon remained active in

city planning. His list of accomplishments is long: He served as vice

president for Montreal-based developer Mondev International, was a professor

at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and the University

of Pennsylvania, was an advocate for downtown renewal programs, narrated

a series of films on urban planning, and organized the 1993 World Congress

on the Post Petroleum City. He also remained a passionate advocate for

his vision for the city and fought to keep his plans intact and moving

forward. In recent years, he lost a bitter battle with the National Park

Service to keep Independence Mall intact and, in 2002, infuriated by

the redesign of LOVE Park (formerly known as JFK Plaza), which he designed

while at Cornell, he briefly rode a skateboard to protest the park’s

ban on skateboarding.

After retiring from civil service in 1970, Bacon remained active in

city planning. His list of accomplishments is long: He served as vice

president for Montreal-based developer Mondev International, was a professor

at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and the University

of Pennsylvania, was an advocate for downtown renewal programs, narrated

a series of films on urban planning, and organized the 1993 World Congress

on the Post Petroleum City. He also remained a passionate advocate for

his vision for the city and fought to keep his plans intact and moving

forward. In recent years, he lost a bitter battle with the National Park

Service to keep Independence Mall intact and, in 2002, infuriated by

the redesign of LOVE Park (formerly known as JFK Plaza), which he designed

while at Cornell, he briefly rode a skateboard to protest the park’s

ban on skateboarding.

In an interview, Bacon was mourned as “one of [Philadelphia’s] greatest citizens” by Pennsylvania Governor Edward G. Rendell. Mayor John F. Street said in a statement, “The example and high standards that Ed Bacon set should be a constant reminder to all of us involved in planning for the expansion and future of our city.” Bacon is survived by six children and five grandchildren.

Copyright 2005 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()

|

||

TIME Magazine, November 6, 1964. Edmund N. Bacon, FAIA. Image courtesy of WHYY-TV, Philadelphia. At the 2000 AIA national convention in Philadelphia, Bacon blows out the candles on a cake held by RUDC member Debra Smith, AIA, in honor of his 90th birthday. (Photo by Douglas E. Gordon, Hon. AIA.)

|

||