10/2005

by

Tracy Ostroff

by

Tracy Ostroff

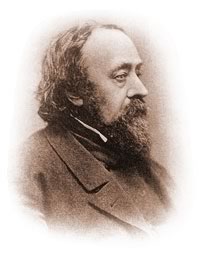

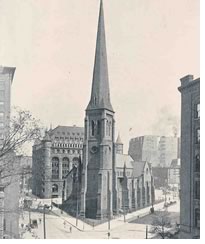

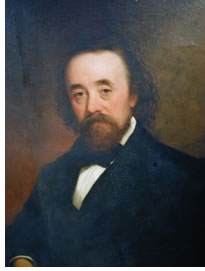

The history of The American Institute of Architects begins with an invitation from Richard Upjohn, architect of Trinity Church in New York City and one of the most famous church architects of his time. He asked his colleagues from the city to gather in his office on February 23, 1857. In response, 12 architects joined Upjohn in the Trinity Building to form the organization that would bring prominence to and profoundly change the profession of architecture in the United States.

The original group included H. W. Cleveland, Henry Dudley, Leopold Eidlitz, Edward Gardiner, Richard Morris Hunt, J. Wrey Mould, Fred A. Peterson, J. M. Priest, John Welch, and Joseph C. Wells, Upjohn's son Richard, and son-in-law Charles Babcock. With clear vision and purpose, Upjohn united this once disconnected community of architects together in fellowship in an organization where they could discuss their common concerns and help define their place in American culture. Such was the esteem that Upjohn’s colleagues had for him that he had to prevail upon them to relieve him of his leadership duties two decades after he helped found the Institute.

“Richard Upjohn had long recognized the unsatisfactory state of his profession and the need for an active organization to foster fellowship among architects, to discuss their problems, and to clarify the various relations of the architect and the community,” notes Richard Upjohn, Architect and Churchman, by E.M. Upjohn (1939). Quickly appointed as chair, Upjohn outlined his general vision for the association to include “regular meetings for discussion of all matters directly or indirectly pertaining to the profession and for greater cohesion and fellowship among the architects themselves.”

The need for an organization that would bring prominence to the profession was clear to Upjohn and his colleagues. Until this point, anyone—masons, carpenters, bricklayers, and other members of the building trades—who wished to call him- or herself an architect could do so. No schools of architecture or architectural licensing laws existed to shape the calling. Although colleagues in Europe were held in higher regard among the public, that was still not the case in America.

From

its inception, the vision of Upjohn and his fellow architects was to

promote “architectural science,” Mary N. Woods notes in

From Craft to Profession (1999).

To advance the continuing education of its members, Upjohn and the others

prepared papers on professional subjects. The first by the new organization

president, E.M. Upjohn notes, was on heating and the best type of flue.

(He concluded that “metal ducts were apt to rust quickly and that

the built-in flues not susceptible to this kind of deterioration were

preferable.”)

In those formative years, the founders settled matters about the organization

itself, from establishing a library and reference materials with architectural

models and drawings and the design of the Institute seal, to larger issues

of professional practice, including ownership of drawings, competitions

for commissions, and standards of practice.

From

its inception, the vision of Upjohn and his fellow architects was to

promote “architectural science,” Mary N. Woods notes in

From Craft to Profession (1999).

To advance the continuing education of its members, Upjohn and the others

prepared papers on professional subjects. The first by the new organization

president, E.M. Upjohn notes, was on heating and the best type of flue.

(He concluded that “metal ducts were apt to rust quickly and that

the built-in flues not susceptible to this kind of deterioration were

preferable.”)

In those formative years, the founders settled matters about the organization

itself, from establishing a library and reference materials with architectural

models and drawings and the design of the Institute seal, to larger issues

of professional practice, including ownership of drawings, competitions

for commissions, and standards of practice.

President Upjohn

Upjohn was appointed chair of the meeting and urged quick action before

the impetus to organize dwindled. At their meeting, the founding members

decided to invite 16 other architects, including A. J. Davis, Thomas

U. Walter, and Calvert Vaux, to the second meeting on March 10, 1857.

A draft constitution and bylaws were read there, and the only change

made was to the name of the organization, from the New York Society

of Architects to The American Institute of Architects. E.M. Upjohn

writes, “At the same meeting, Hunt, as secretary, was directed

to draft two form letters. The first, a notification of election, stated

the initiation fee to be ten dollars and the ‘contributions’ twelve

dollars, payable quarterly. The second, with commendable foresight,

informed the member of his financial delinquency.”

The next month, on April 13, after a luncheon at Delmonico’s restaurant, Upjohn led a small group to New York City Hall to file a certificate of incorporation before Judge James J. Roosevelt. As reported in the minutes of the AIA Board of Directors, the judge said he didn’t worry about the AIA failing because the members were “aware of the necessity of a solid foundation whereupon to construct an edifice & that consequently he felt assured that we had laid our cornerstone on a rock.” Two days later, the members signed the constitution at the chapel at New York University.

“Ripe for change”

Upjohn addressed the members at their first regular meeting of May 5,

1857. Clear from his remarks was his vision for the new organization

and the way in which it would shape the evolution of the profession

in the U.S.:

“A few weeks past we were what we have always been, single handed—each doing his own work, unaided by, and, to a great extent, unknown to each other; possessing no means of interchange of thought upon the weighty subjects connected with our profession, pursuing our individual interests alone, and separately endeavoring to advance, as we are able, each one his own respective position . . . A quarter of a century is sufficient time, nay too long, for an experiment in working to such disadvantage. We were ripe for the change which has resulted in our union, and we may well congratulate each other that we are able to meet on common ground, to consider and execute all those plans which will ‘promote the scientific and practical perfection of its members, and elevate the standing of the profession.’”

The open landscape of America infused in the group a sense of promise

and measured awe. “Throughout this broad land, all is barren space,

a wild, a wilderness. And this paucity of examples will oblige us to

think more intently on our work, to deepen our thought to a more close

and thorough investigation and search after truth, to purity of conception

in our designs, and to a nobler development of the talent committed to

us; and more yet, to an humbler and purer acknowledgement that our talents,

few or many, are gifts from God. . . .”

The open landscape of America infused in the group a sense of promise

and measured awe. “Throughout this broad land, all is barren space,

a wild, a wilderness. And this paucity of examples will oblige us to

think more intently on our work, to deepen our thought to a more close

and thorough investigation and search after truth, to purity of conception

in our designs, and to a nobler development of the talent committed to

us; and more yet, to an humbler and purer acknowledgement that our talents,

few or many, are gifts from God. . . .”

Church architect

Although it’s easy to link Upjohn with the founding of the AIA,

it’s also important to consider his leading role in church and

Gothic Revival architecture. Upjohn, born in Dorset County, England,

was trained as a cabinetmaker. He had his own business in furniture construction

and architectural carpentry. Challenged financially, he sailed for the

U.S. with his wife and small son to live with relatives in New Bedford,

Mass. In 1834 he settled in Boston, working in the office of Alexander

Parris. He started with commissions for residences in Bangor and Gardiner,

Maine, which he designed in the Gothic Revival, a genre that would guide

his esteemed work on protestant Episcopal churches in the northeast and

manifest itself again and again in “Upjohn churches” as America

moved westward.

Referred to as a devout churchman, it is noted that Upjohn considered Gothic the purest form of architecture to represent the Episcopalian faith. Probably the most famous of his commissions, the Trinity parish in New York reflects his reverence for the style and helped establish him as an important American architect. His designs include Saint Paul’s, Buffalo (1850–51); Saint Paul’s Church, Baltimore; and Saint Mary’s Church, Burlington, N.J. His designs helped usher in the three-aisle design with galleries, double pitched roofs, deep chancels, and reversed gambrel roofs with complex woodwork for his larger churches. Such was his commitment to these design principles that clients had to strong arm him away from employing them in their congregations if they were inclined toward a different blueprint. Smaller parishes that could not afford his personal services and newly settled areas were guided by Upjohn’s Rural Architecture, a book to guide the building of parishes, schools, and other buildings that would spread his style across America.

Perhaps it was best that the original AIA charter steered the men away from political discussions, as it is noted that Upjohn found himself in hot water when he reconsidered his decision to design a Unitarian church because, “as a staunch Episcopalian and consequently Trinitarian, he could not design a building to serve as a place of worship for a body whose beliefs were so at variance with his own,” E.M. Upjohn writes. For this he caught considerable criticism at the time—he was termed an “over scrupulous architect”—and the debate lingers as to his motivation for surrendering the commission.

“Upjohn’s domestic architecture forms a body of work that, though it has been overshadowed by the number and quality of his churches, represents his talent and illustrates his search for authenticity in the fitting of style to purpose,” the Macmillan Encyclopedia of Architects notes. He later practiced with his son Richard Michell Upjohn.

A lasting legacy

A lasting legacy

Being the first president of the AIA and a preeminent Episcopalian architect

gave Upjohn opportunities to advance the ideas that were important

to him in his practice and for the profession. For example, he staunchly

defended his right to the ownership of his ideas and drawings. E.M.

Upjohn writes, “The ownership of drawings was always a moot point,

until given some status after the founding of the Institute.”

Upjohn retired from active practice in 1872 and declined to be a candidate for office in 1876, a decision accepted by the members only after his son-in-law, architect Charles Babcock, implored the members to accept his decision. To show appreciation for his 20 years’ effort, a Special Committee of the Tenth Annual Convention made up of the several chapters conceived during his presidency shared a tribute with their beloved leader.

“While we wish, as a body, to tender you our heartfelt thanks for the efficient and able manner in which you have always presided over us, and the kindness and courtesy which you have extended to us personally, we also beg to assure you that the memory of our first President will be a lasting one, not only to the Institute, but in the hearts of its individual members.”

And so his memory remains.

Copyright 2005 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()

|

||

To

learn more about the history of the AIA and the upcoming sesquicentennial

celebrations being planned for 2007, visit the “AIA150” Web

site. Did you know? In 1858 the constitution was amended, enlarging the mission of the AIA “to promote the artistic, scientific, and practical profession of its members; to facilitate their intercourse and good fellowship; to elevate the standing of the profession; and to combine the efforts of those engaged in the practice of Architecture, for the general advancement of the Art.” To achieve these ends, the document called for regular meetings of the membership, lectures on topics of general interest, creation of a library, and development of an architectural model and design collection for the use of the membership. To ensure good rapport, the constitution banned all discussions of a religious or political nature from the meetings. The mission statement remained in effect until 1867, when it was modified to read, “The objects of this Institute are to unite in fellowship the Architects of this continent, and to combine their efforts so as to promote the artistic, scientific, and practical efficiency of the profession.” Over time, these precepts have been further refined, but the basic objectives have remained the same.

|

||