10/2005

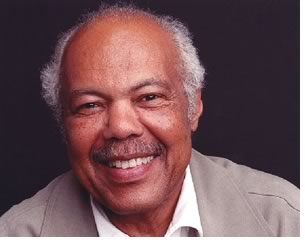

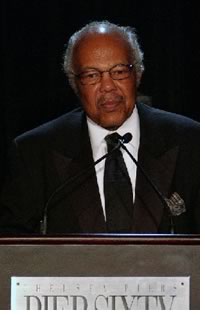

Architect

and educator J. Max Bond, FAIA, partner at Davis Brody Bond, New York

City, on October 6 received the AIA New York Chapter’s President’s

Award at the 2005 Heritage Ball, the major fundraiser for the component

and the Center for Architecture Foundation. The chapter honored Bond

for his commitment to design excellence, activism, and diversity in the

profession. Last week he spoke with AIArchitect about these very issues.

Architect

and educator J. Max Bond, FAIA, partner at Davis Brody Bond, New York

City, on October 6 received the AIA New York Chapter’s President’s

Award at the 2005 Heritage Ball, the major fundraiser for the component

and the Center for Architecture Foundation. The chapter honored Bond

for his commitment to design excellence, activism, and diversity in the

profession. Last week he spoke with AIArchitect about these very issues.

What is the current status of the World Trade Center memorial design?

We just completed the design development stage, which is being reviewed

by the LMDC [Lower Manhattan Development Corporation] and their board.

We’re working jointly with Michael Arad, AIA, and Peter Walker.

They won the competition, and we were then added to the team to help

implement the project. Independently of them, we’re the architects

designing the memorial museum, which will tell the story of 9/11. I

mention all this because the site is very complex, with various other

projects going on. But the state has given a priority to the memorial,

so we’re moving along fairly well on that without some of the

controversy that has emerged over the other sites or some of the issues

that have emerged over the other projects.

As an urban planner, have there been any surprises as the renewal of

Lower Manhattan continues?

People have really become concerned about urban design and architecture

issues in a way that I haven’t seen in New York for awhile! There’s

also concern about the quality of the environment, the designs, and the

architecture. There’s been a great push to really get good architects

and good architecture involved on the various different projects, including

the cultural buildings with Snohetta, the performing arts buildings with

Frank Gehry, the PATH station with Santiago Calatrava, and with a nearby

subway station with Nicholas Grimshaw. There’s quite a distinguished

group of architects working on various sites in the area, so that’s

been a surprise for me as an architect to see the concern that the area

be rebuilt with a great attention to the architecture and some of the

urban design issues.

How can the lessons learned in New York City be applied to the way we

think about rebuilding New Orleans?

One of the things that has been interesting in this whole process—and

really, what the various agencies of government and the LMDC have done

quite conscientiously—is to have a lot of consultation with people

who are involved, including families and the civic alliance here in New

York, which included the regional planning association, a group of architects,

and various other not-for-profit organizations.

From all those meetings, a kind of consensus has emerged about the importance

of the memorial and some of the things that really needed attention.

One of those is to create a memorial precinct as a very serene park-like

area in the midst of a renewed city. On the one hand, there’s been

a great stress for renewing the city; that is, having office buildings,

commerce, housing, and those kinds of things. But within this precinct

that is the memorial itself, the general concept agreed to by a broad

range of people really is due to the extensive efforts to consult with

various groups.

From all those meetings, a kind of consensus has emerged about the importance

of the memorial and some of the things that really needed attention.

One of those is to create a memorial precinct as a very serene park-like

area in the midst of a renewed city. On the one hand, there’s been

a great stress for renewing the city; that is, having office buildings,

commerce, housing, and those kinds of things. But within this precinct

that is the memorial itself, the general concept agreed to by a broad

range of people really is due to the extensive efforts to consult with

various groups.

I think one of the things that will be important in thinking about New Orleans is that even though there is going to be a great rush to rebuild, it’s important that there be consultation with some of the people who used to live there and who were displaced by the storm. I would urge that they really try to initiate a broad consultative process with all of the various parties—with civic groups, with the people themselves—and learn really to listen to all of the concerns that will emerge. The memorial process here in New York has really increased people’s consciousness about the importance of how these decisions are made.

What should be the first thoughts about rebuilding New Orleans?

The first steps should be to look at broader issues beyond some of the

architecture and planning. What we’ve all witnessed about New

Orleans is the really historic divisions engendered by issues of race

and class. One of the things in thinking about rebuilding is to look

at those issues and to think about them in a deeper way than I’ve

seen in the press.

I’m fascinated by how New Orleans distinguishes itself through its culture. It has a really strong cultural identity as a city and a unique one in America. That cultural identity stems very much from the poor people of the city. The music, drama, poetry, and artwork from New Orleans have not been the products of the city’s elites. It’s really of the working class and the poor people of the city. It’s very important for that be recognized. If you read the press, you simply get the impression that these are poor hopeless people, but in fact they have contributed a lot to the culture of the city. It’s very important to keep the culture, and that means providing places for the people who have generated that culture.

Another thing that I’ve been told by those who know the city better

than I is that there should be a really great stress on improving the

educational system of New Orleans and on making better schools. There

was high rate of unemployment in New Orleans before Katrina. Looking

at some of the economic issues, the issues of race and class equity,

in terms of redevelopment, are really important. I’m really afraid

that a lot of that will be swept away in the rush to rebuild. Before

architects start working, I believe there ought to be a broader discussion

about social, economic, and cultural issues to try to set an agenda for

the values that the rebuilding should address.

Another thing that I’ve been told by those who know the city better

than I is that there should be a really great stress on improving the

educational system of New Orleans and on making better schools. There

was high rate of unemployment in New Orleans before Katrina. Looking

at some of the economic issues, the issues of race and class equity,

in terms of redevelopment, are really important. I’m really afraid

that a lot of that will be swept away in the rush to rebuild. Before

architects start working, I believe there ought to be a broader discussion

about social, economic, and cultural issues to try to set an agenda for

the values that the rebuilding should address.

How can this be accomplished?

That’s something toward which the AIA can contribute: Our experience

in getting groups of people together to talk about some of the issues.

I think that would be very important to try to understand how the local

people see the need rather than embark on a top-down rebuilding. First,

there ought to be a real assessment of what the people view as what’s

needed, and maybe a chance to really rethink how the city is put together

in terms of access to social services, jobs, education, and more. I’m

sure talking to local people would generate some new ideas.

To go back to the issue of Katrina, it would be great if architects and local chapters of the AIA and the AIA national component came together not solely to seek work, but to help guide the process and to help represent the people. I think it’s a great opportunity for advocacy architecture and planning. We as a profession can really advocate for the needs of the people who have been so seriously affected by this and by the whole series of events. We have an opportunity really to think about rebuilding a city in a way that better serves everyday people.

How do we encourage diversity in the profession? Who is responsible

for promoting these efforts?

That’s a difficult question. I’ve thought a lot about it

and don’t know that I have a clear answer. One of the things is

that even in the current press about architecture there’s such

an emphasis on the aesthetic aspects of architecture. We’re in

this period of great focus on star architects, as they are called, and

not as much focus on the kinds of things architects do and do quite well

in dealing with social issues and building for everyday people.

One of the things the architecture profession needs to do to encourage

people is to show the range of the profession. There are many ways to

be an architect and contribute to society. People need to feel that there

are broader ways to enter the profession. The reason I mention that is

that the highest levels of design in our profession are still very much

reserved for elite men. You don’t get the celebration of women

as great designers; you don’t get a celebration of people of color

of any kind as great designers. As long as the profession is focused

exclusively on design as its highest level of performance—and it

excludes women and people of color from recognition in those fields—it’s

obvious that you’re not going to attract a lot of women or people

of color to a profession because they don’t see themselves as having

the greatest range of opportunity.

One of the things the architecture profession needs to do to encourage

people is to show the range of the profession. There are many ways to

be an architect and contribute to society. People need to feel that there

are broader ways to enter the profession. The reason I mention that is

that the highest levels of design in our profession are still very much

reserved for elite men. You don’t get the celebration of women

as great designers; you don’t get a celebration of people of color

of any kind as great designers. As long as the profession is focused

exclusively on design as its highest level of performance—and it

excludes women and people of color from recognition in those fields—it’s

obvious that you’re not going to attract a lot of women or people

of color to a profession because they don’t see themselves as having

the greatest range of opportunity.

If, on the other hand, one were to talk about architecture in service to a great many other things, which is, I think, in fact the truth, and then if you show there are people of color and women engaged in those types of service, I think you then might get greater diversity in the profession. This current bias toward aesthetics alone, toward international aesthetic stars is not good in the long run for the profession nor is it something that encourages diversity.

That’s probably an over-simplified answer to a very complicated question, which also has to do with income and how much architects earn as a profession. Our education is as expensive as that for young lawyers and takes as much time. When architects graduate, they make probably a third of what a young lawyer earns. I think this aspect affects the diversity in the profession also. A young African-American who has the ability to go on to get a good graduate education, but who has limited funds, is much more likely—unless they’re absolutely passionate about architecture—to choose another profession.

We are, as a group, responsible. We should emphasize much more of the broad range of things that the profession can do. I think we also need to be involved in the issues that relate to our communities and community organizations. Going back to the development of Lower Manhattan, a lot of architects have become more involved in civic affairs and in the discussions of what the city should be, so that architects are playing a more prominent role in these kinds of discussions. We as a profession need to present ourselves to the world in quite a different way. We also need to emphasize, that while there may be the great star architects, we need to celebrate the people who are not famous, but who are diligent, good, hard-working architects.

What has been the most satisfying part of your career? If you were to

choose another profession, what would it be?

I have gotten a great deal of satisfaction from being an architect. It’s

a way for me to understand the world and it’s a way for me to understand

some of the issues of the world. I think the great potential in architecture

is if you really understand building and urban design and urbanism as

representing core issues in society, you can learn so much by being an

architect by addressing those things instead of just focusing on this

kind of limited aesthetics of it. If you focus on architecture as a representation

of a culture, of a society, of its technology, of its social issues,

then I think it can be a tremendously rewarding profession and one in

which one constantly renews oneself and is educated by just working on

the buildings and working with one’s clients. What’s really

been most satisfying to me is breadth of the profession—what I’ve

been able to learn and benefit from—and in the course of that I’ve

been able to help people and provide some service. That’s terrific.

I grew up in the southern United States, where you could not ignore the various inequities in society and the need for fundamental change. Katrina has illustrated that issues of social justice, economic equity, educational opportunity, are still very much issues that are with us today. So if I were to choose another profession, it would be a profession that addressed those kinds of issues. In my life as an architect, I’ve tried to be involved in practice, in teaching, and in public service. If I chose another profession, I’d try to choose one that would allow me to be involved in similar kinds of things. I found it very rewarding to practice my profession, to teach and learn from the students I was supposedly teaching, and also to be involved in public service and to learn from people about their needs and their emphasis in terms of the economics of society.

Copyright 2005 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()

|

||

|

||