09/2005

Williams College opens world-class performing arts center

Massachusetts’ rural Berkshires can now boast two world-class performing arts facilities, both by Boston’s William Rawn Associates, Architects Inc. The first, the award-winning Seiji Ozawa Hall at Tanglewood in Lenox, is one of the leading arts venues in the region. The second, designed for Williams College in Williamstown, is the ’62 Center for Theatre and Dance opening in October. The $50 million center provides four distinct performance spaces for visiting artists, presenting student works, and hosting the Williamstown Theatre Festival, one of the country’s premiere regional theater companies.

The 212-year-old Williams College is “the archetypal New England town and college,” says William Rawn, FAIA, principal. It has a range of architectural styles that include clapboard, Georgian, Victorian, and 1960s Modern. Also in the New England tradition, town and gown are integrated fully, with students walking through the center of town to pass from dormitory to classroom. “There are some very strong late-19th-century buildings in Williamstown that add a kind of vigor to the architecture and helped us respond to the setting,” Rawn notes. “Although it’s clearly a contemporary building, the ’62 Center follows the pattern of buildings along Main Street in that it is strongly perpendicular—narrow in the front and deep in the back. We wanted the center to be a strong building of its time like the other buildings on Main Street.”

Unique in purpose; united in feel

Unique in purpose; united in feel

Named for the college’s Class of 1962, which led its fundraising

efforts, the ’62 Center offers a range of performance spaces, each

with a unique purpose and character but all united in seeking a feeling

of intimacy, both for the spectators and the artists, many of whom will

be students unused to performing in front of an audience. The venues

include:

- The elegant MainStage Theatre, a 550-seat proscenium theater with two balconies wrapped in ash paneling

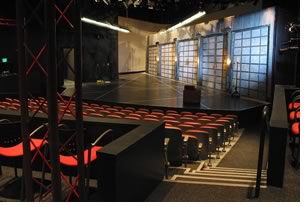

- CenterStage—the “work-horse of the theater department”—a 200-seat flexible black-box theater with moveable balconies, a lift, and a massive steel sliding door that opens onto a lobby

- The 250-seat Adams Memorial Theater, designed by Cram and Ferguson and built in 1941, which was renovated as a “thrust-type theater” and embedded in the new complex

- A 50-foot by 65-foot dance studio for intimate dance and music recitals, with floor-to-ceiling glass walls on three sides that provide dramatic views of the Berkshire Hills.

The center also offers abundant teaching and technical spaces for the

theater department and dance programs. At 106,000 square feet, the facility

greatly enhances the capabilities of the performing arts departments

of this small liberal arts college of 2,000 students.

The center also offers abundant teaching and technical spaces for the

theater department and dance programs. At 106,000 square feet, the facility

greatly enhances the capabilities of the performing arts departments

of this small liberal arts college of 2,000 students.

Catherine Hill, provost, John J. Gibson Professor of Economics, and co-chair of the ’62 Center planning committee says that when both departments were previously housed in the Adams Memorial Theater, “We were tight on space for the dance and theater programs. We now have wonderful facilities. Having all groups in one space will allow them to interact in a really wonderful way. Nearly all visiting artists will conduct workshops that will be integrated into the curriculum. This integration began over the summer, with the Williamstown Theatre Festival, and is already benefiting students.” The ’62 Center opened to the students in the spring but has its official opening September 30–October 9 with readings and musical, theater, and dance performances by visiting artists, students, and alumni.

Forging connections

Forging connections

Located in a prominent position on campus, the center seeks to build

on the students’ liberal arts education by forging connections

between the performing arts and other courses of study. Rawn notes

that “the real power of the building is that it has brought the

teaching of theater to the forefront.” In most performing arts

venues, the front- and back-of-house (rehearsal and break-out spaces,

costume and scene shops, etc.) operations are kept separate. One of

the primary goals with this project was to integrate the two and make

both accessible to students and visitors alike, thus celebrating the

art and craft of the performing arts.

“The focus of the design is on the students,” reports Rawn. “We incorporated a through-promenade that dissects the building, connecting the Greylock dormitories and dining hall to the main campus, making a special effort to have the public pass through the educational spaces. Along the promenade is the CenterStage Theatre, which has a 20-foot-high and -wide door that opens up to the public hallway and lobby.” Rawn says that the hope is that, as non-theater/dance students pass by CenterStage, they will become fascinated by what they see and increase their range of exposure. This is the essence of the traditional liberal-arts experience. “Guests arriving at the center for a performance will park in the garage and proceed through a plaza and into the back of the building, making the public pass through nearly the whole building to get to the public spaces,” he notes.

The

MainStage lobby is a glass cube with a prominent overhang and wood shutters

that provide a sense of warmth and ample natural light deep into the

interior spaces. The curved limestone façade acts as

a foil to the contemporary lobby and provides context to the surrounding

structures. As students and visitors progress from the wood and glass

lobby to the Adams Memorial Theater and CenterStage, the materials change

to reflect an adjustable industrial setting with metal, steel, and glass.

The dance studio is located off the promenade and is accessed by a monumental

staircase.

The

MainStage lobby is a glass cube with a prominent overhang and wood shutters

that provide a sense of warmth and ample natural light deep into the

interior spaces. The curved limestone façade acts as

a foil to the contemporary lobby and provides context to the surrounding

structures. As students and visitors progress from the wood and glass

lobby to the Adams Memorial Theater and CenterStage, the materials change

to reflect an adjustable industrial setting with metal, steel, and glass.

The dance studio is located off the promenade and is accessed by a monumental

staircase.

The biggest overall challenge, says the architect, was organizing the venues. “In a facility that has only two performance spaces, the layout is relatively simple. They share a lobby, and the back-of-house operations are kept hidden,” he says. “Here, we have it organized around three main venues and back-of-house operations. The main promenade through the building was generated as a result of this challenge.”

“A real gem”

The second challenge was how to bring a very contemporary building into

the very traditional Williamstown setting. Rawn believes that because

most of the townspeople are familiar with Ozawa Hall at Tanglewood, “it

gave them a confidence that we wouldn’t go too out of character

and do something atrociously out of place.”

Indeed, according to Hill, “Bill Rawn did a great job of coming

to campus and listening to the users of the building. He took into account

the needs of the student performers as well as those of the visiting

artists and audience. The intimacy of all the resulting spaces is just

wonderful. CenterStage is an intimate, small, flexible space where you’re

right there with the actors. In the old Adams Memorial Theater, there

were about 500 seats, with many of them pretty far away from the stage.

At a performance this spring in the MainStage Theatre, we sat in the

second balcony and still felt like we were right there. And the dance

studio has to be the most beautiful space on campus with its 270-degree

view of the mountains. There aren’t any other buildings with that

kind of view. In the ’62 Center, we have a real gem.”

Indeed, according to Hill, “Bill Rawn did a great job of coming

to campus and listening to the users of the building. He took into account

the needs of the student performers as well as those of the visiting

artists and audience. The intimacy of all the resulting spaces is just

wonderful. CenterStage is an intimate, small, flexible space where you’re

right there with the actors. In the old Adams Memorial Theater, there

were about 500 seats, with many of them pretty far away from the stage.

At a performance this spring in the MainStage Theatre, we sat in the

second balcony and still felt like we were right there. And the dance

studio has to be the most beautiful space on campus with its 270-degree

view of the mountains. There aren’t any other buildings with that

kind of view. In the ’62 Center, we have a real gem.”

Copyright 2005 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()