09/2005

When is an ugly house beautiful?

For Don Pruett, Assoc. AIA, project manager at Samaha Associates in Fairfax, Va., an ugly house is a beautiful thing when it helps sixth-grade students get the hang of conceptual thinking in architecture.

And one ugly house leads to award-winning design models for students at Hunters Woods Elementary school in Reston, Va.

Teaching outside an “ugly” box

Teaching outside an “ugly” box

Pruett became involved with Hunters Woods Elementary School for the Arts

and Sciences through sixth-grade teacher Lisa Foley, who instituted

the Architecture in Schools program at her school. The program puts

architects in elementary, middle, and high schools to help teachers

teach architecture. It is sponsored by the Washington Architectural

Foundation.

“It was more of an after-school enrichment program, and what we wanted to do is to teach them about architecture from the conceptual design point of view, not necessarily to teach them about familiar architects,” says Pruett.

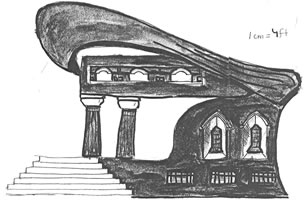

The Hunters Woods students did three projects in eight weeks. “The first was an icebreaker project where they got into teams and designed and built a model of an ugly house,” says Pruett. “This was quite challenging because the first thing they wanted to do was to make something pretty, and when we said it has to be ugly their mouths dropped. What we got at the end of the hour session was a model that one team called the Cathedral de Picasso. It was a wilting, drooping mass of materials that they put together. Meanwhile, I went out and found architecture that related to their design, and they were fascinated to see that architecture existed that they thought was ugly, which then became purely beautiful in their eyes once they saw it. After we sat them down and talked about it I told them ‘you just experienced conceptual thinking.’ This set up the next sessions, because they started thinking about architecture differently.”

Raising the roof

Raising the roof

The next step was a two-session program called Raise the Roof, a national

design and sculpture competition sponsored by The Maryland-National

Capital Park and Planning Commission’s Department of Parks and Recreation

in Prince George’s County, Md. The competition’s call for entries

was last fall, and it stressed personal designs of “home” that

could be developed into works of art. It was open to artists, architects,

designers, engineers, homebuilders, families, and students of all ages.

“We had the sixth-graders explore non-traditional ways of thinking about housing,” explains Pruett. “We had the children thinking that houses were not necessarily living rooms and dining rooms and kitchens. What are the events that go on at home? What is a kitchen used for? They started seeing architecture differently in response to everyday events that go on in their lives.”

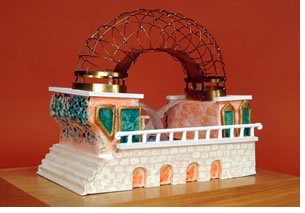

Seven of 13 designs, none of which followed a traditional pattern, were selected to advance to the next round of competition: The Igloo House, The Tape House, The Dog House, The Mailbox House, The Telephone House, The Stapler Building, and The Round House. Each design received an $800 honorarium to construct a three-dimensional architecture model for each design for the next step of the competition. Foley had already had the students working with clay and art modeling. Pruett started teaching them architecture modeling techniques. The models were to be 18 inches in length with various widths and heights.

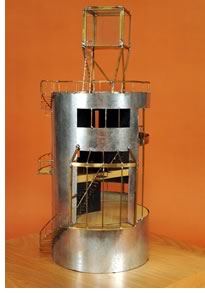

“I

taught the kids how to solder brass, work with bass wood, foam core,

copper wire, and tubing,” explains Pruett. “The Round

House was actually constructed out of a round, galvanized duct, sliced

and diced. On its outside were soldered elements such as stairs, railings,

windows, balconies, and a glass cube soldered to the roof. For the floors

the kids took basswood and laminated it to foam-core board. For the

walls, I taught them how to use acrylic paint and dabble it on the walls

to give it a mottled effect. They built inside staircases of soldered

brass. The Round House won a $2,000 prize for Adaptive Re-Use of Materials.

“I

taught the kids how to solder brass, work with bass wood, foam core,

copper wire, and tubing,” explains Pruett. “The Round

House was actually constructed out of a round, galvanized duct, sliced

and diced. On its outside were soldered elements such as stairs, railings,

windows, balconies, and a glass cube soldered to the roof. For the floors

the kids took basswood and laminated it to foam-core board. For the

walls, I taught them how to use acrylic paint and dabble it on the walls

to give it a mottled effect. They built inside staircases of soldered

brass. The Round House won a $2,000 prize for Adaptive Re-Use of Materials.

“The Mailbox House, which won an honorable mention award, was made of foam core and lathered up with drywall compound so it looked like a mailbox but it’s all white. The kids worked hard slicing up foam and putting plaster on the foam to get unusual shapes. For the roof of the Stapler House the girls must have carved for a week and then put the compound and plaster on it. I think they all performed at the high school level. And this was the only school selected to advance.”

Pruett says he never discounted teaching the sixth-graders traditional architecture. “I just presented the explorations that you can do in today’s architecture,” he expounds. “For example, I used Santiago Calatrava’s work as an example. A lot of his buildings are derived from the human form. I showed the students Calatrava’s eye-shaped L’Hemisfèric [planetarium at Valencia, Spain’s City of Arts and Sciences]. I showed the students the sketches of how Calatrava drew the eyeball’s lid, or roof, opening and closing, and how it looks in daytime and nighttime, and how it reflects in the water. They were fascinated by the idea of how something can become what it is by using a different type of architectural approach.”

The major award (The Round House), the honorable mention (The Mailbox

House), and the honorariums brought the Hunters Woods art department

a combined $8,100.

The major award (The Round House), the honorable mention (The Mailbox

House), and the honorariums brought the Hunters Woods art department

a combined $8,100.

Judges for Raise the Roof included Garth Rockcastle, dean of the School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation at the University of Maryland at College Park, and Jay Martin Endelman, award-winning builder and member of the Housing Initiative Partnership Board of Directors in Prince George’s County. The models are currently on exhibit through September 14 at the Arts/Harmony Hall Regional Center in Fort Washington, Md. After three more stops (details in the reference column, right), the models will be auctioned off to raise funds for low-income housing for artists.

What the students learned; how architects can benefit

Pruett believes that the sixth-graders learned how design architects

think. “They definitely got the idea of conceptual thinking about

architecture . . . seeing things differently. They also learned

modeling techniques that architects use to visualize their work, that

is, taking sketches to a three-dimensional conceptual model where you’re

not worried if it really works yet but you see how the spaces relate

to each other both two-dimensionally and three-dimensionally. Also,

they learned how to make their sketches come to a scale. So, at the

exhibits, you see a close uniform scale in all the models.”

He notes that emerging AIA professionals and associate members in their

interning years should become involved in teaching young students about

architecture. “I think [emerging professionals] would be tremendous

assets to architecture firms that hire them. There’s something

that can be said about being involved in the community this way.”

He notes that emerging AIA professionals and associate members in their

interning years should become involved in teaching young students about

architecture. “I think [emerging professionals] would be tremendous

assets to architecture firms that hire them. There’s something

that can be said about being involved in the community this way.”

And what of the young, sixth-grade minds?

“I believe students like those at Hunters Woods will become advanced in the way that they view architecture,” Pruett points out. “They will not be caught up in the traditional way of looking at things.”

Now that is not an ugly finish.

Copyright 2005 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()

|

||

Once the exhibit at the Arts/Harmony Hall Regional Center in Fort Washington, Md., ends September 14, the models travel to the School of Architecture, University of Maryland, College Park, for display from October 5 to October 31. In November, the models will be at the Montpelier Center in Laurel, Md., finishing off from December 1 through January 20, 2006, at the Huntington Community center in Bowie, Md.

|

||